Chester County, Pennsylvania

Essay

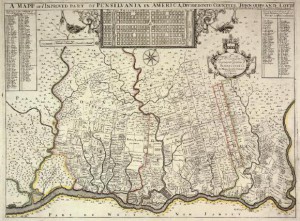

As one of the original counties established by William Penn (1644-1718), Chester County was only modestly influenced by Philadelphia in its early development because after 1789 it shared no border with the city. Although the Pennsylvania Railroad linked the county’s central valley to Philadelphia in the mid-nineteenth century, it remained a largely rural landscape whose farms, mills, and forges operated within a mostly self-sufficient economy while sending surpluses to the Philadelphia market. Not until the second half of the twentieth century did dramatic changes come to its pastoral landscapes and small towns. Starting in the 1970s the arrival of financial services firms along with bio-medical research and development companies drew thousands of new residents, turning it into a county of farms plus pharma.

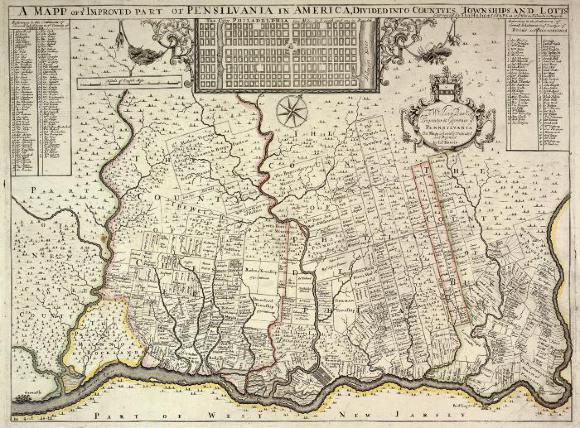

Lenni Lenape (also known as Delaware), along with some Dutch and Swedes, already lived in the area before Penn laid out the county boundaries stretching more than one hundred miles from the Delaware River to the Susquehanna River. That initial county structure proved too large to serve its inhabitants well. In 1729, provincial authorities carved out Lancaster County, then in 1752 shifted a small part to Berks County as well. Not long after the American Revolution, the residents in the western portion of the remaining county objected to traveling so far to conduct business in the county seat at Chester City on the Delaware River. They wanted a county seat located farther west. They got their wish when West Chester became the county seat, and three years later, in 1789, Delaware County was carved out. From that time, Chester County no longer shared a border with Philadelphia.

Penn had encouraged the early formation of townships covering the entire territory as a way to promote self-government. Many boroughs and townships had incorporated by the early eighteenth century, for example Caln in 1686, Kennett in 1704, Uwchlan in 1712, and numerous others. But the Quakers who predominated in much of Chester County shunned town living, preferring life on their farms. Based on religious scruples, Quakers showed little interest in formal governance of their territory. Except for the county seat, early towns carried few public responsibilities beyond providing small local marketplaces and serving as units for assessing taxes. Rural families produced a large share of the goods for home consumption, and craftsmen lived among the farmers, trading their products for food.

Transportation Routes Shaped Settlements

The land formation known as the “Great Valley,” stretching from the Schuylkill River in Montgomery County to the southwest through Chester and Lancaster Counties, provided early travelers with a natural route. The first major east-west road following the Great Valley westward was the Lancaster Road or the Great Road, which became the most traveled route of its time. Benjamin Rush (1746-1813) in 1789 remarked of German farmers that it was “no common thing, on the Lancaster and Reading roads, to meet in one day fifty to a hundred of these [Conestoga] wagons on their way to Philadelphia, most of which belong to German farmers.”

Largely following that same route, the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Road Company constructed in 1795 the first long-distance paved route in the United States stretching sixty-two miles between Philadelphia and the city of Lancaster. The improved road bed allowed farmers and craftsmen to haul heavy freight and drive stage coaches from Lancaster to Philadelphia. It brought travelers to dozens of inns, taverns, saddleries, and shops of every variety, and helped build Downingtown and a few other commercial centers along its route.

To serve the southern part of the county, the state chartered the Philadelphia, Brandywine and New London Turnpike Company in 1808 to build a stagecoach road from Philadelphia to Baltimore. That route, known as the Baltimore Pike (designated Route 1 in 1926), entered Chester County from Delaware County at Chadds Ford and ran through the Brandywine Valley—a mix of farms and woodland, as well as commercial towns and villages like Kennett Square. Farmers in the Brandywine Valley hauled their grain to mills powered by the Brandywine River, which also powered paper mills that supplied Philadelphia printers.

Railroads exerted less impact on early settlement patterns in Chester County than in other suburban counties around Philadelphia because the rail network was less densely built on the western edge of the region. The great exception was the Main Line, a railroad designed as one component of a larger network of canals and rails that the state government sponsored in order to help Pennsylvania compete commercially against New York State. Construction started in 1829, carried on largely by Irish immigrants. In 1857 the Pennsylvania Railroad purchased the line since known as the Main Line.

Across the middle of the county, investors built the Philadelphia & Baltimore Central (P&BC) railroad just before the Civil War. They broke ground in 1855 in Concord Township in Delaware County, where the celebrants tossed one shovelful of dirt toward Philadelphia and another toward Baltimore to signify the goal of connecting the two cities.

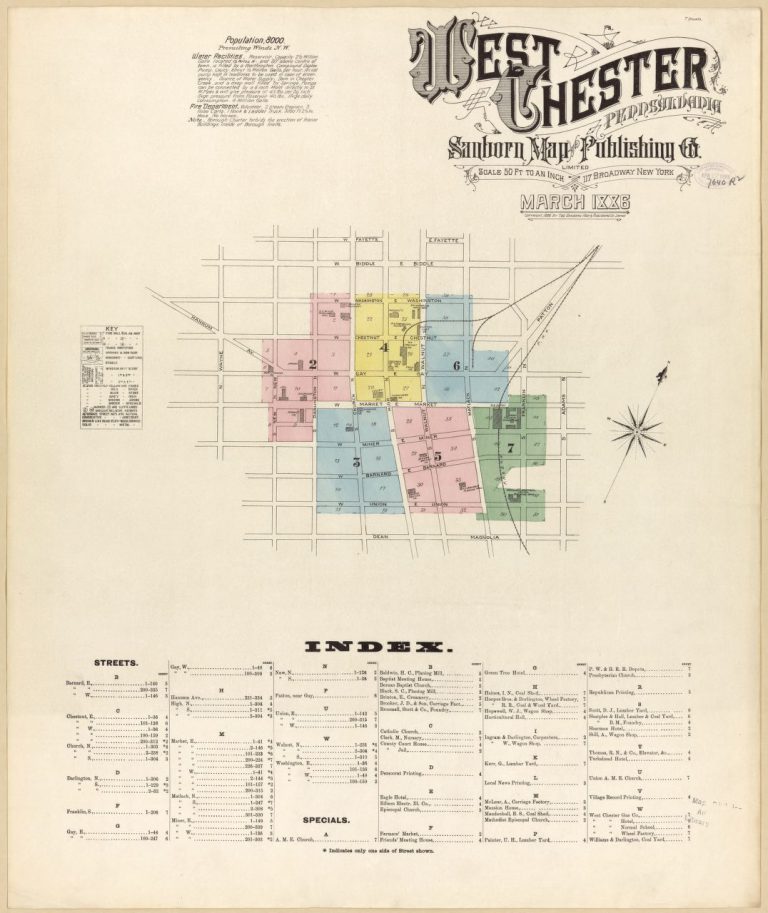

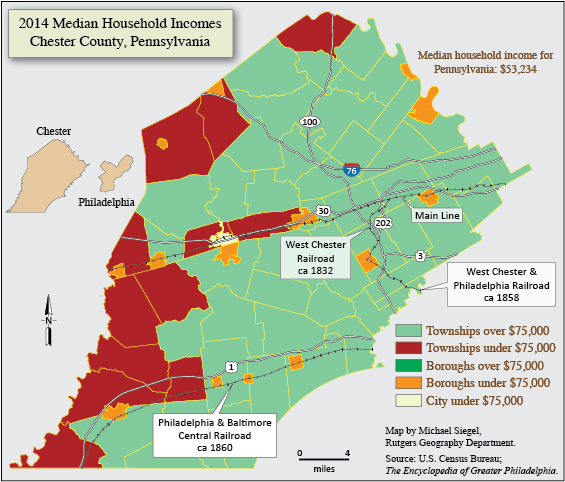

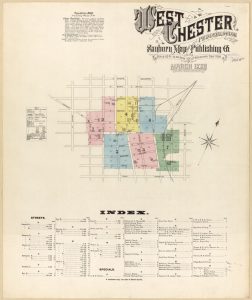

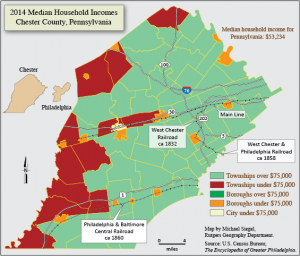

As those two major lines crossed the county from east to west, they helped spur the economies of some towns along the way, including Downingtown and Coatesville on the Main Line and Oxford Borough on the P&BC near the county’s southern border with Maryland. But their main function was to link Philadelphia to the distant cities of Lancaster to the west and Baltimore to the south. One of the few places within the county that did purposely build rail lines to spur its own development was the county seat of West Chester, where business leaders formed a railroad company to connect their town to the Main Line running some miles to the north. They opened the West Chester Railroad (WCRR) in 1832 to carry both passengers and freight. In the 1850s a second group of investors built West Chester & Philadelphia Rail Road (WC&P) to offer an alternative connecting West Chester to the Philadelphia & Baltimore Central line running through southern Delaware and Chester Counties. During the period of railroad consolidations around the turn of the twentieth century, the Pennsylvania Railroad gained control over both West Chester railroads, as well as the Main Line and the Philadelphia & Baltimore Central.

Agriculture and Industry

Abundant sources of water power made milling the county’s first industry. Farmers grew corn, wheat, barley, oats, rye, buckwheat, and flax, and most settlements had a grist mill, which could also be used as a sawmill. However, as improved transportation networks made long-distance shipping easier, farmers shifted away from diversified crops to produce more livestock. The growth of Philadelphia and increasing purchasing power of the population persuaded farmers to supply more meat. By mid-nineteenth century, agriculture in Chester County focused most heavily on grazing and dairying. The 1860 agricultural census showed that of Chester County’s roughly fifty thousand cattle, half were for dairy and the other half for beef purposes.

Water power enabled the county’s residents to exploit the area’s rich iron ore deposits. Early iron manufactories established a basis for nationally-known ironworks. In 1790 on the banks of French Creek, the French Creek Nail Works opened the first nail factory in the United States, later renamed the Phoenix Iron Company. It grew into an extensive ironworks consisting of furnace, foundry, rolling-mill, and nail factory. During the Civil War, Phoenix Iron produced the Griffen Gun and became a major supplier of the Union Army. As railroads multiplied, the company focused on structural steel for bridge building, a crucial requirement for railroad expansion.

Lukens Steel in Coatesville was born in 1810 when Isaac Pennock (1767-1824) began the Brandywine Iron Works and Nail Factory on the banks of the Brandywine River. All the raw materials needed—iron ore, limestone, and hardwood forests for charcoal—were available in the Coatesville area. In 1813 Pennock’s daughter Rebecca (1794-1854) married Charles Lukens (1786-1825), who oversaw the operation of his father-in-law’s business. When Lukens died in 1825, Rebecca took over operation of the steel mill. She managed the business until 1849 and turned it into the top producer of boilerplate in the country.

Agriculture continued to operate profitably throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, aided by the rail lines that crossed the county. By the 1890s, the Pennsylvania Railroad trains that ran all the way to Lancaster gave farmers in western Chester County a way to ship fresh milk and produce daily to Philadelphia. In 1906 Abbott’s Dairy opened in Oxford on the far west side of the county yet still transported its products to the Philadelphia market.

Plant cultivation contributed significantly to the county economy. In the borough of West Grove In 1868 the Dingee & Conard Nursery Company began growing and selling fruit trees, roses, and other nursery products. They pioneered the use of mail order catalogues, and by the late 1880s shipping of their nursery products made West Grove the second-largest post office in Chester County. The company became nationally known for its roses, most notably the Peace Rose. In 1945, the company provided one of this specially bred flower to every international delegate meeting in San Francisco to establish the United Nations.

Undoubtedly mushrooms became Chester County’s best-known food crop. In the 1890s William Swayne (1851-1950), a florist in Kennett Square, began growing mushrooms in the unused space underneath his greenhouse benches. Because he required precise regulation of the temperature, humidity, and air quality, Swayne erected the first building to be used exclusively for mushroom growing, and Kennett Square eventually became the national center of mushroom cultivation. Ironically, old-fashioned mushroom cultivation helped build Chester County’s twenty-first century specialization in bio-life sciences. Starting in the 1920s chemist G. Raymond Rettew (1903-73) began providing testing services to area mushroom growers. He devised a process for growing penicillin that made mass production of the drug possible. He sold the idea to Reichel Laboratories of Phoenixville, which was acquired by Wyeth in 1943. The penicillin case demonstrated the important process of turning research into production that became a hallmark of Chester County’s high tech economy.

Social Disparities

From the start, Chester County’s population contained both rich and poor. In 1800, the wealthiest 10 percent of the county’s households paid 38 percent of the taxes, and the poorest 30 percent of the citizenry paid only 4 percent. To house the poor and unemployed, county leaders in 1798 built a Poor House about eight miles from West Chester on the banks of the Brandywine Creek. On 325 acres, they built a large brick building and a barn to house a working farm. This county almshouse system replaced the aid provided by individual townships. The intent was to provide a more consistent level of care and a more efficient use of funds. Reflecting their shared belief in the value of work, they required every able body to work, even the children. Residents of the Poor House sold homespun cloth, brooms, smoked meats, and even quarried limestone.

Early European settlers held African slaves, though in relatively small numbers. In Chester County the number of slave owners reached 4 percent of taxpayers in 1759. The strong Quaker influence in the affairs of the county discouraged slavery as did economic factors. At the start of the Civil War, African American residents represented about 8 percent of Chester County’s population; although a modest share, that was the highest percentage of African Americans in the counties of southeast Pennsylvania. Those free African Americans worked for hire or owned their own small businesses.

Chester County residents included people who actively embraced the social reform movements of the mid-nineteenth century such as anti-slavery, women’s rights, and temperance. Local European Americans, primarily Quaker, and African American abolitionists concealed runaway enslaved people who traveled from the South through the mid-Atlantic and north to safety in Canada. Anti-slavery sentiment was particularly strong in Kennett Square, a center of abolitionism. Disagreement over the authority of Quaker meetings and how best to address the issue of slavery led to the establishment of the Pennsylvania Yearly Meeting of Progressive Friends in 1853 (Longwood Yearly Meeting). The Longwood Meetinghouse opened in 1855. Its annual meetings hosted radicals and reformers such as Sojourner Truth and William Lloyd Garrison. County residents also hosted the first Pennsylvania Woman’s Rights Convention in June 1852 in West Chester, advocating for equal legal, social, economic, and political rights, including suffrage.

The African American population grew after the Civil War, when iron companies in Phoenixville and Coatesville recruited Black workers in the South as a way of discouraging European immigrants from striking for higher wages. Animosity between working-class white and Black people came to a head in Coatesville in 1911 with the horrifying death of Zachariah Walker, a Black man who was literally burned alive by a white mob after his conviction for killing a white guard at a local steel plant.

In part to address social inequality, the Society of Friends supported education for all children. As early as 1787 the Kennett Monthly Meeting began raising funds to support “schooling the children of such poor people, whether Friends or others, as live within the verge of the Monthly Meeting.” For the offspring of more affluent families, the county was dotted by dozens of single-sex boarding schools, for example West Chester Academy, a private, state-aided school opened in 1813. It went through a series of transformations across the years that resulted in its becoming West Chester University. In 1854 the Pennsylvania legislature incorporated another of Chester County’s prominent educational institutions as Ashmun Institute for the education of young men of color, a name that changed in 1866 to Lincoln University.

Despite important efforts to promote broad social advancement, the county entered the twentieth century with wide disparities among its residents. Wealthy families built rural retreats on large estates, many of them designed in the Victorian style popular among early twentieth century architects. West Whiteland Township, served by the Pennsylvania Railroad running along the Main Line, boasted an impressive collection of such homes. Important Philadelphia architects built many of them, for example the Francis W. Kennedy House designed by Frank Miles Day (1861-1918) in 1889 for a vice president of the Wilkes-Barre and Western Railway; the Joseph Price House, an older structure that was extensively altered in 1894 for a wealthy Philadelphia surgeon; and Meadowcourt (sometimes called Autun) which was designed by Edmund Gilchrist (1885-1953) in the French style in 1928 for insurance executive Benjamin Rush Jr. Owners of these large properties pursued diversions like foxhunting, for which a group of well-to-do families established the Whitelands Hunt.

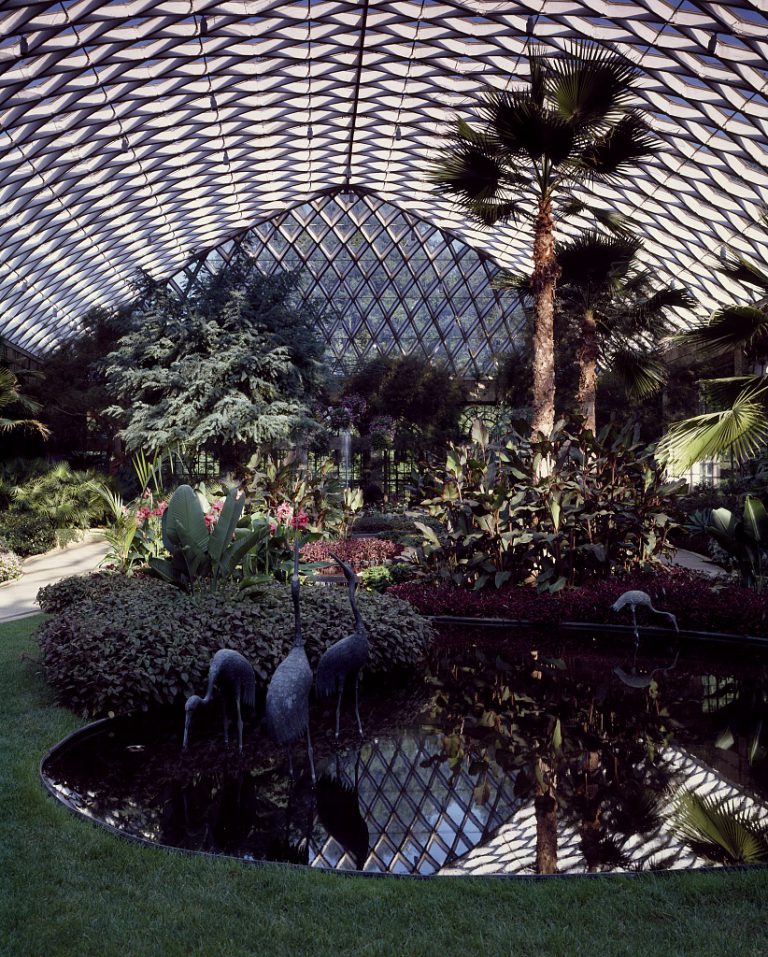

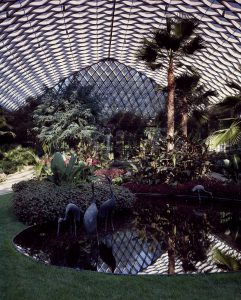

In the Brandywine Valley in 1906 Pierre S. Dupont (1870-1954) of the wealthy Delaware Dupont family bought the Peirce Farm in Kennett Township and created an estate of incomparable beauty. He repaired and expanded the original Peirce farmhouse, connecting new and old wings with a conservatory whose courtyard was planted with exotic foliage and a marble fountain. In 1923, he added an elegant music room with walnut paneling, damask-covered walls, teak floors, and a molded plaster ceiling, opening onto the central axis of the main greenhouse. Dupont named his estate Longwood Gardens for the nearby Longwood Meeting House built by Quakers.

At the other end of the social spectrum, in nearby communities of southern Chester County, immigrants lived in deplorable conditions. Around the turn of the twentieth century, southern Europeans came to the county. One of the county’s most successful plant nurseries, Hoopes Brothers & Thomas in West Chester, began hiring Italian immigrants in 1906 because they could not find enough local labor. By 1908, newspapers were criticizing these immigrant workers for drying their laundry on the outside of their shanties. Despite the social stigma the Italians stayed, and a century later 16 percent of West Chester residents still claimed Italian ancestry. In industrial towns like Coatesville and Phoenixville, Eastern Europeans, notably Hungarians and Poles, served as a significant source for factory labor.

Puerto Ricans initially arrived in Chester County after World War II, while Mexicans arrived in the 1960s. Recruiters brought them to Pennsylvania to farm labor-intensive crops like vegetables, fruits, and mushrooms. Kennett Square, the center of mushroom production, attracted a substantial Spanish-speaking population, as did the smaller community of Toughkenamon a mile west of Kennett Square.

Limited by their very low wages and undocumented status, many immigrants settled for dilapidated, overcrowded houses, apartments, or mobile homes. In 1994 the Alliance for Better Housing composed of clergy, mushroom growers, and local officials began working to improve housing conditions for farm workers and other low-income residents in southern Chester County. Additional help came from local organizations like United Way, La Comunidad Hispana, PathStone, Mission Santa Maria, local food cupboards and local churches.

Newcomers from South and East Asia lived a completely different immigrant experience from the mushroom workers in southern Chester County. Hired into knowledge economy jobs, they clustered in affluent townships along Route 202 or Route 30—for example, East Whiteland, West Whiteland, East Caln, and Upper Uwchlan—in the northeast section of the county, where they worked in technology and finance companies.

The county’s rapid economic ascent after 1980 attracted a workforce equipped to prosper in the knowledge, finance, and service economy. The 2014 American Community Survey showed that 49 percent of county residents had college degrees, the highest percentage among suburban counties surrounding Philadelphia. Of the population 25 years or older, 92 percent were high school graduates, 49 percent had a bachelor’s degree or higher, and 20 percent had a graduate or professional degree. In 2010, it was the highest-income county in Pennsylvania and twenty-fourth highest in the U.S. as measured by median household income.

Not all towns shared that success. Because of its reliance on the steel industry, the city of Coatesville suffered the most visible and dramatic setbacks in the county. Lukens Steel had flourished there since the early 1800s, building major national projects from the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge to the Battleship USS New Jersey. But faced with competition from foreign steel producers, in 1982 the company reduced its workforce by 22 percent between January and September 1982 and cut the pay of salaried employees by 10 percent. After 187 years of continuous operation, Lukens Steel Company sold its Coatesville operation to Bethlehem Steel Company, which in turn sold the plant to new international owners. Each new owner reduced the workforce, so that by the end of the twentieth century the steel plant that had employed over six thousand workers at midcentury provided jobs for fewer than one thousand.

These contrasting fortunes yielded substantial differences in tax resources available to town governments, and that in turn produced unequal public services. Among the fourteen school districts in Chester County, the highest-spending district, the Great Valley School District, serving the high tech corridor, spent $20,588 per student in 2015 while the lowest-spending district, the Oxford Area School District in southern Chester County, spent barely more than $13,000 per student. To worsen inequalities, lower-spending districts were educating larger shares of low-income children. In 2015 only 14 percent of the school population in the high-spending Great Valley School District had incomes low enough to qualify for free and reduced-price lunches. That same year, the low-spending Oxford Area School District served a student body in which 40 percent qualified for subsidized lunches.

Development patterns

The Pennsylvania Turnpike (Interstate 76) dramatically altered development in the northeast section of the county. Builders completed the Chester County section of the Turnpike in 1950. Designed as a limited-access route to allow fast travel across Pennsylvania, the Pennsylvania Turnpike initially provided just two exits located within Chester County (Downingtown and Malvern/Phoenixville). Those two exits became focal points for growth, as did the Valley Forge/King of Prussia exit located in Montgomery County right at the border with Chester County.

Another example of an expressway influencing development was Route 202, a highway dating back to 1926. In 1964, the Pennsylvania Department of Highways designed a continuous four-lane expressway along the US 202 corridor, opening the section of that new expressway south from King of Prussia toward West Chester in 1967. Over the next several decades that stretch of Route 202 attracted hundreds of computer-related companies, biomedical concerns, and other service and information- based firms.

Suburbanizing relatively late, Chester County in the 1970s offered developers a chance to acquire huge open parcels on which to build a series of high-profile and often controversial industrial parks. Some occupied more than a square mile of ground, making them larger than some boroughs in Chester County. Businessman Raymond Carr (1925-2015) built Chester County’s first industrial park on what had previously been cornfields. Carr and his partner David Knauer (1928-2011) recognized the value of farmland sitting near the Downingtown exit off the Pennsylvania Turnpike, which was the only connection to the national superhighway system in Chester County. In 1965 the partners bought 180 acres for sale in Lionville and turned them into Pickering Creek Industrial Park, a collection of more than a dozen multipurpose buildings that housed companies specializing in product testing, manufacturing, and eventually biotechnology and life sciences.

In 1969 not far from the Turnpike’s Valley Forge exit, developer Richard Fox (b. 1927) bought Chesterbrook Farm, located between the turnpike on its northern border and Route 202 on its southern border. His plan, unusual for combining residential neighborhoods with a corporate complex, faced stiff public opposition when unveiled in 1971. Opponents feared that the traffic it generated would negatively impact Valley Forge State (later National) Park. The ensuing legal battle went all the way to the state Supreme Court. Hundreds of residents attended meetings and signed petitions against construction, but eventually Fox prevailed and began to build housing in 1977, gradually adding a shopping center, restaurants, corporate offices, and a hotel, along with open spaces.

The business complex that launched Route 202’s reputation as Tech Alley was the Great Valley Corporate Center, started in 1974 on pasture land located between a landfill and a quarry. Philadelphia-based developer Willard Rouse (1942-2003) convinced young companies to locate in his new development by building facilities to their specifications and helping them finance the move to Chester County. Biotechnology companies valued a location that put them close to Philadelphia universities and medical centers and at the same time close to pharmaceutical companies like SmithKline, Merck, and Rhone-Poulenc Rorer.

Also in the mid-1970s, Willard Rouse’s uncle, James W. Rouse (1914-96), built the Exton Square Mall. The Maryland developer acquired a tract of land at the intersection of Route 30 and Route 100 that held little more than a few gas stations, a drive-in movie, a diner and a motel, and built his mall there in 1972. Exton Square remained a major retail center well into the twenty-first century. Its size and scope attracted additional services, including a public library, the Exton Transportation Center with connections to the King of Prussia Mall, and medical facilities.

Watching such large-scale, master-planned developments multiply during the 1970s and 1980s, Chester County residents feared the loss of open land and the road congestion that such developments brought with them. Those apprehensions brought an end to one of the most ambitious proposals ever considered in the county. In 1987 Willard Rouse announced plans to build Churchill, a 1,500-acre mixed-use development on Church Farm School property on Route 30 in Exton. That unspoiled expanse of cornfields was so massive that it spanned parts of four townships, forcing Rouse to negotiate for years with multiple local governments to secure permission to build. In the end the sheer scale of development proved too much for local residents. Both East Whiteland and West Whiteland townships denied Rouse permission to build.

Taking control of development patterns

From 1969 to 2000, Chester County lost over 26 percent of its farmland to development. If that pace had been allowed to continue, all of the county’s farmland would have been paved over within forty years. To stave off such a future, the county government adopted a dramatic and far-reaching plan titled Landscapes: Managing Change in Chester County to shape its growth until 2020. The plan prescribed preserving open space while directing future development into already-existing towns, to ensure Chester County would remain attractive as a place for knowledge industries to locate. Although the county government could do little more than offer technical assistance for implementing the plan to local governments that retained control of land use under Pennsylvania law, nonetheless by 2015 about one quarter of the land area in the county had been permanently preserved.

Some private developers fell in line with county plans by making investments that reduced the number of auto trips workers needed to make each day. For example, the owners of Great Valley Corporate Center redesigned their auto-dependent complex to incorporate everyday services like day care, fitness centers, stores, and restaurants within a walkable mixed-use development. Other developers saw opportunities in older boroughs like Phoenixville and West Chester to reinvest in Victorian structures and community character that would attract residents.

Still other builders sought to create new housing on smaller-than-standard-size lots so they could permanently preserve open space for the pleasure of community residents. They found local zoning laws a major stumbling block. A 2007 book written about one company’s effort to build a high-density housing development dubbed “New Daleville” showed how difficult it was to convince town officials to adjust standard zoning to allow a village-style approach with small lots and shared open space. The developer persisted and eventually succeeded, but not without enormous resistance from residents who supported more conventional subdivision designs.

In one important respect, Chester County’s late suburbanization proved a blessing. It gave county leaders a greater chance to preserve farms, wooded areas, and historic landscapes than in other counties in the Philadelphia region. Yet the negative consequence of delayed development was that Chester County possessed even less public transit than neighboring counties. Chester County entered the twenty-first century with little hope of convincing motorists to abandon their cars. The county’s heavy auto dependence, combined with a pattern of erecting massive job centers along major highways, virtually ensured that traffic congestion would continue to be its residents’ unceasing complaint.

Carolyn T. Adams is Professor Emeritus of Geography and Urban Studies at Temple University and associate editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. This essay incorporates information and suggestions provided by Laurie A. Rofini, Archives Director, and Cliff C. Parker, Archivist, of Chester County Archives and Records Services and Chester County Historical Society. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Aiming to help Chester, Philly residents move to better opportunity, housing program starts off slowly (WHYY, January 20, 2016)

- A bench? A park? Chester gets grant to crowdsource ideas for beautifying downtown (WHYY, May 11, 2016)

- Fearing crackdown on labor, Chester County mushroom growers urge hybrid status for immigrant workers (WHYY, April 27, 2017)

- Chester County delegates to China led to deals for mushrooms, beer (WHYY, May 15, 2017)