Northwest Philadelphia

Essay

Northwest Philadelphia, bound loosely by the Roosevelt Expressway to the south, Broad Street to the east, and the suburbs of Montgomery County to the north and west, has origins as old as the city itself. Developing around the Schuylkill and Wissahickon Creek waterways, and later Fairmount Park, the Northwest expanded and changed with the advent of new technologies and the larger legal, political, and cultural trends of Philadelphia.

In the late seventeenth century, as William Penn (1644-1718) worked to establish his “green country town,” the German Township along the Wissahickon came together as a small community of Dutch Mennonite and German Pietist immigrants, bound at first by religious and cultural identity. On August 12, 1689, Penn granted the group its own charter, creating a distinct Germantown borough with a mayor, council, court, and marketplace.

The community prospered in the cloth trade, as townspeople worked as linen weavers, and also gained a reputation as a seedbed of antislavery agitation. In 1688, German Quakers published a resolution condemning the “traffick of men-Body.” In 1775, the French-born Anthony Benezet (1713-84), a longtime resident of Germantown, founded the first abolitionist society in the United States, the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage, later the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, and by 1800, 60 free blacks (and seven slaves) were recorded as living in Germantown.

This legacy of activism persisted in parts of the region, even as it maintained an identity as a largely white and wealthy enclave. For many of Philadelphia’s elite, Germantown – with its relatively high elevation at 336 feet, offering scenic views and lazy breezes – became a popular respite from the frenzy of the city. In 1750, loyalist William Allen (1704-80), later Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, built a country estate at what is now Germantown Avenue and Allens Lane, and called the home Mount Airy, bestowing the name for the neighborhood that two centuries later earned a national reputation for racial tolerance.

Industry-Related Growth

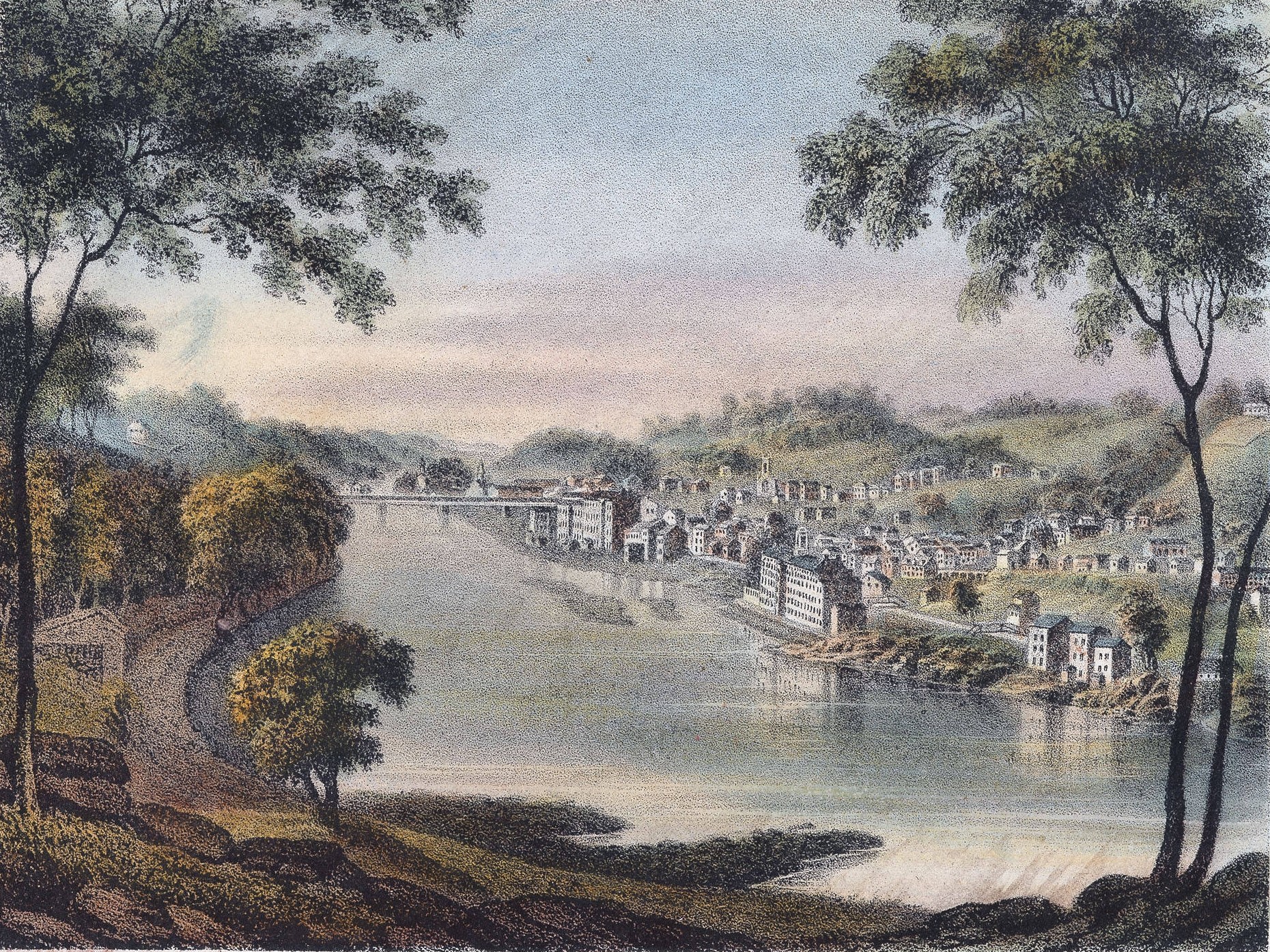

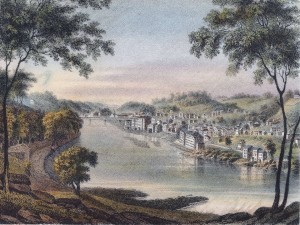

In the early nineteenth century, as Philadelphia entered the age of industrialization, the Northwest region grew precipitously. In 1815, the city granted a charter to the Schuylkill Navigation Company, charged with improving the navigational system of the Schuylkill River. Less than a decade later, the 108-mile waterway reached completion, linking Philadelphia with the coalfields of Port Carbon and Pottsville. These advancements brought new life to the communities along the river.

Across the Wissahickon Gorge from Germantown, the borough of Manayunk, part of the larger Roxborough Township and ideally positioned in the river valley, experienced massive development, largely due to local textile manufacturing. From 1817 to 1824, the population expanded from 60 to nearly 800 people, and by the late 1820s the community, which just a few years earlier contained little more than a toll house, had become known alternately as the “Lowell of Pennsylvania” and the “Manchester of America.” In 1840, the town was incorporated as its own separate borough. The owners of the Manayunk mills resided above the town on the ridge between the river and the Wissahickon, which along with Germantown became one of the wealthiest communities in Philadelphia County.

Until 1854, these northwest communities retained their independent charters and systems of governance. On February 2 of that year, though, the General Assembly of Pennsylvania and Governor William Bigler (1790-1879) approved the Act of Consolidation, dissolving the townships, boroughs, and districts that surrounded the city and incorporating the entirety of Philadelphia County under the authority of the Philadelphia municipal government.

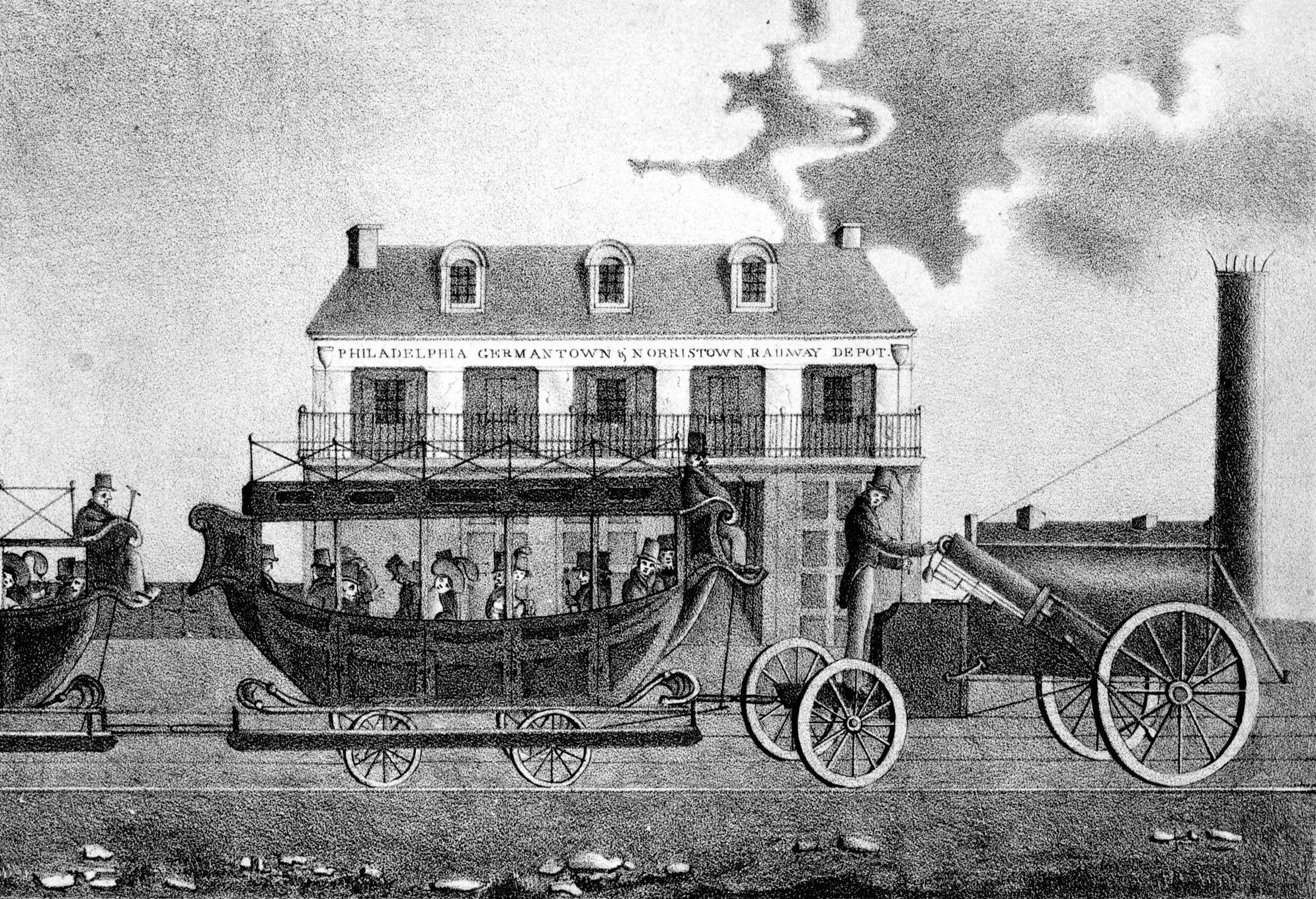

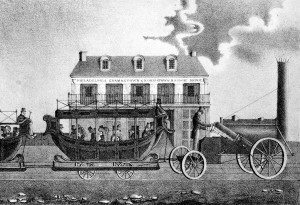

As this legislative action brought the region under the auspices of city institutions and services, the expansion of the railways opened up the city and made the area more accessible. In the early 1830s, a group of Germantown entrepreneurs set out to create the Philadelphia, Germantown, and Norristown Railroad. The earliest trains arrived in Germantown in 1832, and the community soon developed into the first Railroad Suburb in Philadelphia, and one of the first in the nation. Within a year, the wealthy residents of Chestnut Hill, occupying the northernmost section of Germantown, clamored for a regular stagecoach service to connect their large pastoral plots on the Hill to the Germantown Depot at Germantown Avenue and Price Street. Two decades later, more reliable horse car and steam rail service came to Germantown, carrying multi-passenger vehicles along the iron rails. In Chestnut Hill, local commuters raised funds for a permanent railroad connecting the southern and northern ends of Germantown. The new terminal at Chestnut Hill Avenue and Bethlehem Pike opened on July 3, 1854.

Influx of City Residents

With these political and technological changes, the region rapidly expanded. The influx of city residents prompted new housing development throughout Northwest Philadelphia, but even as population surged, residents held strong to each community’s independent roots.

It was, in part, the green space around these northwest neighborhoods that allowed homeowners to maintain their autonomy from the rest of the city. Fairmount Park (officially incorporated in 1855) and its forested Wissahickon Gorge acted as a buffer between Germantown and Roxborough and the rest of Philadelphia County. But even the Wissahickon, which had served as the stage for the Battle of Germantown in 1777, felt the effects of the city’s industrial growth. At the turn of the eighteenth century, the region had become home to the first two paper mills in North America – the first built by William Rittenhouse at the south end of the gorge in 1690, the second by William Dewees at the northern end in 1708. By 1850, the dense woods and deep valley were home to more than 50 water-powered mills. Mining and blasting broke through the steep cliffs along the southern end of the creek, giving way to the development of the Rittenhousetown mills, and by 1856, the Wissahickon Turnpike, a private toll road, ran through the valley south to north. In the latter half of the 1800s, efforts to protect and preserve the water source prompted the Fairmount Park Commission to take over the land, demolishing the mills and in their place erecting several inns and lodges, where visitors could enjoy the natural splendor that remained.

By the turn of the century, the population of Northwest Philadelphia was beginning to change. From 1910 to 1930, more than 140,000 African Americans arrived in the city in the first wave of the Great Migration from the South to northern cities. As they settled in South, West, and North Philadelphia, long-established residents began to move outward, creating greater ethnic diversification in the Northwest. Many Italian-Americans left South Philadelphia for the Roxborough area. German, Scots-Irish, and Irish families moved to Germantown.

As the population shifted, the economy also prompted vast changes. First, road construction along the Schuylkill River connected Northwest Philadelphia to the city center, making automobile travel a reality for the first time. Then, the Great Depression of the 1930s brought the closing of most of the mills along the Schuylkill River corridor, and such neighborhoods as Manayunk and East Falls saw their industrial prowess begin to wane. Many of the large mansions of Chestnut Hill – by the late nineteenth century one of the most elite neighborhoods in the United States – were demolished as the most affluent residents lost fortunes in the stock market. This also led to job losses for the large service economy that existed in the area.

With the Second World War, the city once again experienced new growth with a second mass migration of African Americans. Philadelphia’s black population increased from nearly 251,000 in 1940 to 376,000 in 1950. At first, most upwardly mobile black newcomers concentrated in North Philadelphia. After World War II, though, as these increasingly all-black neighborhoods experienced an acute housing shortage, middle-class African Americans also began to move outward to the Northwest.

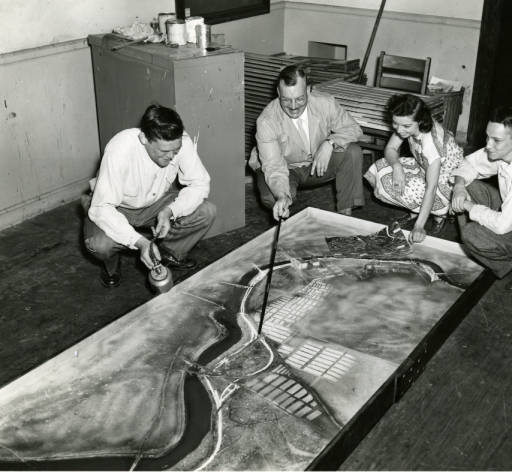

When the war ended, communities on the outer edges of the city saw their under-developed green space quickly fill with new housing. Although Northwest Philadelphia saw less physical development than other areas of the city, the region still underwent widespread growth. Upper Roxborough experienced development much like the surrounding Montgomery County suburbs, with new houses, green front lawns, and strip malls spreading along Henry and Ridge Avenues. New neighborhoods sprung up along the northwest city borders, including the westernmost pocket of Andorra and West Oak Lane to the east.

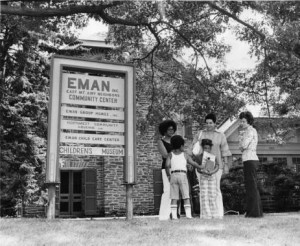

In southern Germantown, the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority allocated $10.6 million for public housing, to contend with the growing numbers of black families moving into the area. West Mount Airy, the community in the central section of historic German Township named for Justice Allen’s 1750 home, began to develop its own identity as an economically viable, racially integrated community. Unlike other areas of the region and city, where white residents responded to the arrival of black families with “fight or flight,” community leaders in the upper-middle class neighborhood created a proactive plan toward interracial living. By the early 1960s, the community was touted across the nation as a site of racial progress. Its counterpart across Germantown Avenue, East Mount Airy, experienced a brief period of integration before transitioning to a predominantly black middle-class population. Throughout the next decade, similar patterns of white flight and African American settlement took hold in West Oak Lane and Germantown. Across Northwest Philadelphia, churches, schools, and neighborhood organizations offered critical institutional support during these postwar years, helping residents navigate these periods of transition and preserve a sense of community identity.

By the last decades of the twentieth century, as the Northwest section became more enmeshed in the Philadelphia economy and as individual communities responded to the larger political, economic, and cultural forces of the city, the regional identity of the area began to wane. Even as efforts toward local preservation, restoration, and oral history collection highlighted the living history of the region, Northwest Philadelphia became less a cohesive entity than a loosely connected group of neighborhoods, still bound by the common heritage of the natural woodlands of the Wissahickon, the industrial might of the Schuylkill canal, and the desire for independence as well as strong community ties. Perhaps more than any other section of the city, Northwest Philadelphia retained William Penn’s historic mission to create a green country town in an urban center.

Abigail Perkiss is an Assistant Professor of History at Kean University in Union, N.J. She is the author of Making Good Neighbors: Civil Rights, Liberalism, and Integration in Post-War Philadelphia, published by Cornell University Press. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Grassroots group seeks cash from wealthy alumni to turn GHS plan into action (WHYY, February 28, 2014)

- Crews gather along the Schuylkill for the 76th Aberdeen Dad Vail Regatta (WHYY, May 10, 2014)

- Millennials drawn to Northwest Philly, but will they stay put? (WHYY, May 19, 2014)

- Northwest Philly congregation celebrates overturning of same-sex marriage ban (WHYY, May 22, 2014)

- Weinstein rails against Local 98's 'desperate ... focus on Northwest Philly' (WHYY, May 27, 2014)

- Zoning board delays decisions on St. Bridget and W. Johnson St. development projects (WHYY, June 12, 2014)

- Scenes from the first day of school in NW Philadelphia [gallery] (WHYY, September 8, 2014)

- $1.1 million state grant aims to better connect Northwest Philly (PlanPhilly, November 20, 2014)

- Scenes from MLK Day of Service in Northwest Philadelphia [photos] (WHYY, January 20, 2015)

- Northwest Philly wins big with city-sponsored arts grant (WHYY, February 26, 2015)

- Philadelphia Cultural Fund helps support over 30 Northwest Philadelphia arts organizations (WHYY, May 11, 2015)

- Yards Brewing Company to celebrate 20 years with a toast to its humble beginnings in Manayunk (WHYY, May 14, 2015)

- In Germantown, real hope rises for better days ahead (WHYY, June 15, 2015)

- Haywood seeks to start a 'reading revolution' for children in Northwest Philly (WHYY, July 7, 2015)

- Revolutionary Germantown Festival brings historic reenactment to Northwest Philly (WHYY, October 5, 2015)