Bucks County, Pennsylvania

Essay

Bucks County, one of three counties established in 1682 by William Penn (1644-1718), originally stretched northward along the Delaware River all the way to the Delaware Water Gap and westward past Allentown. Even after shrinking dramatically when Northampton and Lehigh Counties were carved from its territory in 1752, the county still encompassed multiple regions that developed along different historical trajectories. A largely bucolic Upper Bucks County remained distinct from the areas that became blue-collar Lower Bucks County and the white-collar townships of Central Bucks County. This tripartite division shaped many institutional patterns, from colonial-era disputes about where to locate the county seat to twentieth-century decisions to create three chambers of commerce and divide the county’s community college into three campuses.

Lenni Lenape people resided in the area before Europeans arrived. In 1640 Swedes purchased parts of Lower Bucks County from the Lenape, and a handful of Swedish settlers began building log houses in the region. In July 1682, William Penn’s agent purchased other lands from the Lenape, which eventually became the townships of Bristol, Falls, Middletown, Lower and Upper Makefield, Newtown, and some of Wrightstown. When Penn arrived in Pennsylvania later in 1682, he chose to build his family’s manor house, which he called Pennsbury, in Falls Township.

English newcomers first settled the lower portion of Bucks County along the Delaware River, but soon the abundant and fertile land available farther north drew them upward to Newtown, Wrightstown, and Buckingham Townships. Other religious reformers unwelcome in Europe followed the English Quakers, including German Mennonites and Lutherans, Dutch Reformed, Welsh Quakers, and Baptists.

The town of Bristol, which afforded the county’s only port with access to the Atlantic Ocean via the Delaware River, served as the first county seat from 1705 to 1726. But early sectional differences arose when residents living in Central and Upper Bucks complained about the long distance they traveled to do business. So officials moved the county seat northward to Newtown in 1726. Even Newtown, however, proved too distant for settlers in Upper Bucks, who grumbled that they had “long labored under the great disadvantage of having the courts of justice held in a place very un-central in Bucks County.” That forced the legislature in 1810 to authorize three commissioners to select a new county seat, instructing them to choose a location within three miles of the exact geographical center of the county. They picked Doylestown, which remained the county seat across the centuries.

Significant Role in the Revolution

Bucks County played a significant role in the Revolutionary War. In 1776, the army of George Washington (1732-99) camped in Central Bucks, using it as a base for his Trenton campaign. On the night of December 25–26, Washington famously crossed from Bucks County into New Jersey to win the battle of Trenton. After securing that victory, Washington returned to Pennsylvania and quartered his men at Newtown. August 1777 found Washington’s army camped in Bucks County, this time in Warwick Township, on its way to the Battle of Brandywine. Again in 1778, his army camped at Doylestown.

Although Upper Bucks was more sparsely populated than other sections of the county during the revolutionary period, a group of German farmers there attracted national attention by fomenting the so-called Fries Rebellion in 1798-99. Having just overthrown British taxation without representation, residents in the northwest corner of the county balked at paying a new federal property tax that President John Adams (1735-1826) invented to fund another war that the U.S. expected to face with France. (As it happened, that war never broke out.) Federal troops quickly quelled the rebellion.

Agricultural Surpluses

As early as 1700, farmers began producing substantial surpluses and found they needed roads that extended all the way to the markets of Philadelphia. To construct those long routes, early road builders often linked together a series of shorter spans. They strung these routes across the county from northeast to southwest so that farmers and craftsmen in different sections of Bucks County could move their goods southwesterly toward Philadelphia.

Early dirt roads were unreliable enough to suffer a strong challenge from canals in the early 1800s. Canals proved especially important in transporting coal and iron from the Lehigh Valley to Bucks County communities. In 1827 the Pennsylvania legislature authorized construction of a canal from Easton, Pennsylvania, south to Bristol in Bucks County. The first section of that canal ran between New Hope and Bristol in 1830, and the rest of the waterway up to Easton opened two years later.

To supplement the canals, investors upgraded roads to become “turnpikes.” Private companies applied to the provincial government for permission to reinforce dirt roads with crushed stone to make them sturdy enough to support heavy wagonloads. The turnpike companies then required travelers to pay tolls at intervals along the route to cover the costs of improving and maintaining the road.

One of the early turnpikes ran along the banks of the Delaware River, connecting Philadelphia to New York. Called the King’s Highway (later Route 13), it followed an existing Native American trail. The road was laid out in 1686 by order of William Penn. After critics deplored “ye unevenness of ye road from Philadelphia to ye falls of Delaware,” its maintenance was assigned to the Frankford and Bristol Turnpike company, incorporated in 1803. Farther north from the Delaware River, the Route 1 turnpike became an informal boundary line separating the old river towns of Lower Bucks from Central Bucks County.

East to West on Route 202

About halfway up the county, Route 202 emerged out of a string of shorter roads, many of which were already in place by 1800. The national government brought those individual stretches into the national highway system in 1927 as Route 202. When connected together, they crossed the county, linking New Hope on the eastern boundary of the county to Doylestown and Chalfont on the western side. In Upper Bucks, residents of Bedminster Township could travel southwest on Bedminster Road (later Route 113) as far as the border with Montgomery County, and there pick up the Bethlehem Pike that would take them all the way south to Philadelphia.

The diagonal orientation of roadways (running from northeast to southwest) reinforced the county’s historical separation into three regions. An important exception to that travel pattern was Dyers Mill Road, later called the Easton Road (now Route 611). It opened in the 1720s connecting Doylestown to Montgomery County and eventually stretched all the way up to Easton. But the dominant road pattern reinforced lateral connections between communities, with weaker linkages between the northern and southern parts of the county.

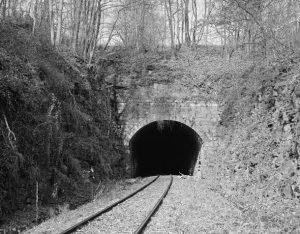

The coming of railroads did little to alter those cross-county travel patterns. In 1833 the Philadelphia and Trenton Railroad Company built the county’s first rail line. It ran between Philadelphia and Trenton via Bristol. That line was acquired in 1873 by the Pennsylvania Railroad, which also operated a second east-west line across Bucks County farther north to link other Bucks County towns with Trenton.

Other lines operated by the North Pennsylvania Railroad spanned the county from west to east. For example, in 1856 the North Pennsylvania Railroad Company built an offshoot from its north-south route that carried passengers and freight east to Doylestown. In 1855 that same company also built a line across Lower Bucks through Yardley to Trenton, an expansion that continued to operate after the Reading Railroad leased routes from the North Penn Railroad Company in 1879 and operated them as part of the Reading system. (That route eventually became the West Trenton line of SEPTA’s regional rail system, and commuter trains shared the track with freight operations by CSX Corp.) In 1891 Reading also chose to significantly expand a short line running from Warminster to Hartsville, all the way across the county to New Hope on the Delaware River.

The North Pennsylvania Railroad

An important exception to the east-west pattern of early railroad lines ran through the northwest corner of Bucks County. In the 1850s the North Pennsylvania Railroad extended a line from Philadelphia north to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, to carry both passengers and coal from the Lehigh Valley. That Bethlehem line passed through the Upper Bucks towns of Sellersville, Perkasie, Telford, and Quakertown.

At the close of the nineteenth century, trolleys became the “poor man’s railroad.” Doylestown occupied the center of a countywide network of street railways. Initially the Bucks County Electric Railway Company and later the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company ran a trolley line between Doylestown and Willow Grove, later adding lines to Newtown and Easton. By 1902 a twenty-six-mile network connected Doylestown to many other county places, including Bristol, Hulmeville, Penndel, and Langhorne.

Patterns of Production

Agriculture furnished livelihoods for the early Europeans, who favored growing wheat, partly because it required a few periods of intensive labor, while leaving farmers free at other times to tend other crops like flax and potatoes. When the adoption of fertilizer allowed farmers to feed more livestock, they began to shift toward dairy cows that produced butter and cheese in large enough quantities to sell. Farmers often combined agriculture with mills for processing grains as well as lumber.

Along the Delaware River, investors built mills producing textiles and paper. The river port of Bristol attracted ship building in the early decades of the eighteenth century. In 1727 a group of Philadelphia investors built the county’s first iron furnace at Durham in the far northeast corner of the county. The Durham iron works forged cannonballs and other munitions for Washington’s colonial troops.

After a canal built in 1830 had connected Lower Bucks with Easton and other upriver towns, mills in Bristol relied on Pennsylvania coal to drive their machines. In 1876 William Hulme Grundy (1836-1893) moved his Grundy Brothers and Campion woolen mill from Philadelphia to Bristol, partly to escape from union organizing by the Knights of Labor. There it became Bucks County’s largest industrial employer and made Bristol the county’s manufacturing center.

In both Lower and Upper Bucks County, the cigar industry proved to be a major economic force. In both places, many farmers raised tobacco. Government records in 1871 reported 470 manufactories of cigars in Bucks County as well as one snuff-mill at Bristol. Even in the largely-agricultural spaces of Upper Bucks, cigar factories served as important employers during the first half of the nineteenth century. When the North Pennsylvania Railroad opened through Quakertown in 1856, it connected those cigar makers with new suppliers and markets, spurring new factories in several towns where the railroad stopped, including Quakertown, Sellersville, and Perkasie. The collapse of Cuban tobacco plantations during the Spanish-American War helped the Pennsylvania producers, but ultimately the mechanization of the industry during the 1890s undercut their profits and drove many out of business by the 1920s.

Heavy Industrial Development

The early decades of the twentieth century brought heavy industrial development to Lower Bucks, particularly in shipyards along the Delaware River, where land was cheaper than in the city and the river afforded easy access to Philadelphia and other Atlantic ports. When Averell Harriman (1891-1986) built the Bristol shipyards in 1917, that enterprise spawned not only shipbuilding but also related business. At about the same time, Rohm and Haas Chemical Company built a plant that remained a major force in the town’s economy for decades. During World War II, shipyards were converted to build airplanes. But by the 1960s, these factories stood empty, victims of a combination of obsolete technology and higher costs than competitors were facing in the American Sunbelt and overseas.

The rise and fall of heavy industry in Lower Bucks County involved multiple industries and companies, but is best captured in the history of United States Steel Corporation. In 1952 that company built its Fairless Works in Falls Township. Within a year, the facility employed nearly eight thousand workers in the main plant and adjacent shops. That plant became a symbol of post-World War II prosperity. Yet the Fairless Works could not withstand relentless competition from overseas steel manufacturers. By 2001, the company had shut down virtually the entire massive plant except for a small galvanizing facility.

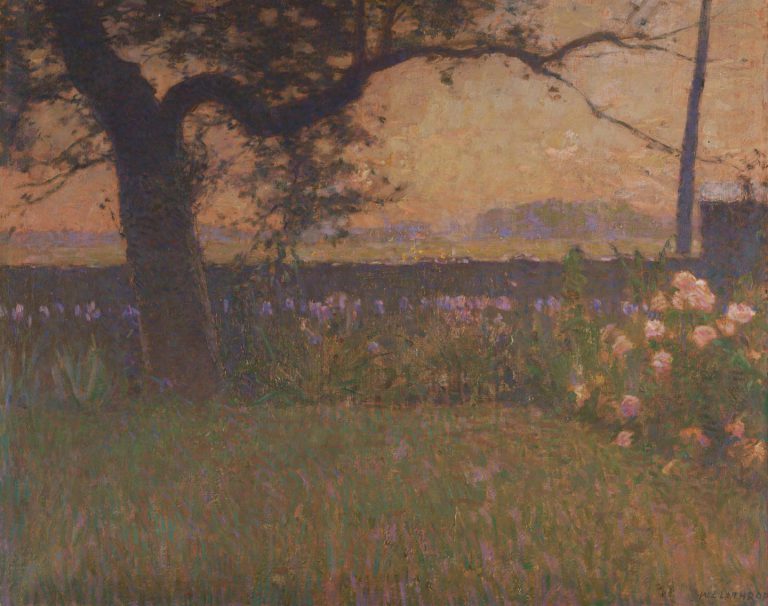

Compared with other parts of the county, Central Bucks distinguished itself in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the production of arts and literature. As early as 1815, Quaker artist Edward Hicks (1780-1849) worked there, painting the image of The Peaceable Kingdom that would make him a celebrated folk artist. However, the real influx of artists to migrate to Central Bucks began when the painters William L. Lathrop (1859-1938) and Edward Willis Redfield (1869-1965) each moved there in 1898, drawing other painters and sculptors to the area around New Hope. The work they and their followers produced would ultimately be dubbed “Pennsylvania Impressionism.”

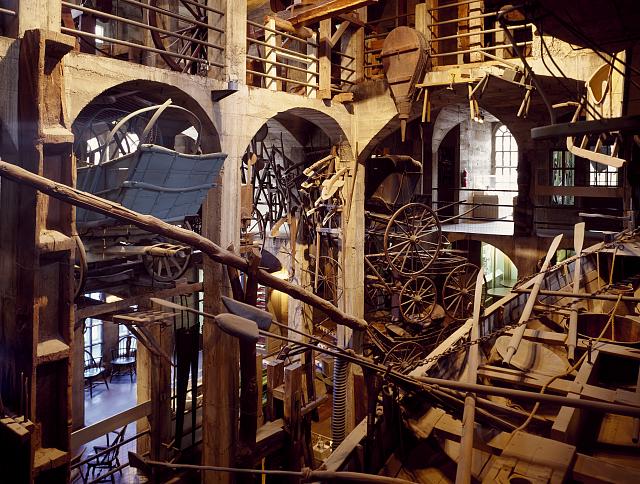

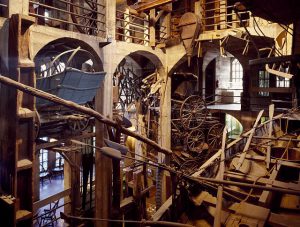

Another cultural force was the Arts & Crafts tile maker Henry Mercer (1856-1930), who built his Doylestown home Fonthill as a castle where he designed tiles, gathered an extensive collection of tiles, prints and tools, and conceived (and later built) an equally fanciful castlelike museum for the collection of the Bucks County Historical Society (renamed the Mercer Museum after his death).

“The Genius Belt”

During the 1930s Bucks County also gained a reputation as a haven for novelists, playwrights, actors, and songwriters. New Yorkers bought properties in the small stretch between Doylestown and New Hope and along the Delaware River, including Margaret Mead (1901-78), Pearl Buck (1892-1973), Oscar Hammerstein 1895-1960), Stephen Sondheim (b. 1930), Charlie Parker (1920-55), Moss Hart (1904-61), George S. Kaufman (1889-1961), James Michener (1907-97), Dorothy Parker (1893-67), and S. J. Perelman (1904-79). Their numbers and notoriety led the novelist Michener to dub this part of his native Bucks County “the genius belt.”

Despite the demise of heavy industries in the late twentieth century, Bucks County retained some manufacturing, although not the kind that could provide employment for workers operating milling machines and assembly lines. By the turn of the twenty-first century, knowledge-based enterprises like finance and other business services, along with biotechnology and pharmaceuticals, required college-educated workers.

An early turn toward high technology took place at the Naval Air Warfare Center in Warminster. Originally in the 1930s a private company built an aircraft assembly plant there. However, by 1942 the U.S. Navy had become so frustrated by the firm’s inability to deliver on contracts that it bought the plant to operate as a government facility. Over the decades, the Navy built one of the most important research and development facilities in the United States, developing early prototypes of global positioning systems (GPS) and constructing a centrifuge that trained NASA astronauts for space. The Naval Air Warfare Center closed in 1996 in a wave of military cutbacks, and the land was converted to a park and residential and commercial developments.

Fortunately for the local economy another important aerospace facility, Lockheed Martin, opened in Newtown in 1996, when Holy Family College transferred fifty-two acres to the company. The Newtown facility served as the headquarters for Lockheed Martin Commercial Space Systems, which employed scientific and technical staff in the research, design, and development of satellite systems. In 2010, the company invested in a lavish new 15,000-square-foot building that added to the facility’s manufacturing capabilities as well as conference facilities. Only three years later, however, Lockheed Martin announced that it would close its Bucks County facilities along with several other plants, in response to cuts in federal defense spending required by the sequester of 2013.

High-Tech Innovation

Again, Bucks County demonstrated its resilience. KVK-Tech, a specialty pharmaceutical company producing generic drugs, quickly acquired Lockheed’s Newtown facilities. KVK-Tech used the site to create a high-technology business incubator, moving its research and development teams there as well as leasing space to high-tech small start-ups, especially in pharmaceuticals. The draws for KVK-Tech included the strong pharmaceutical workforce residing in Bucks and Montgomery Counties, plus Central Bucks’s highly-rated schools and amenities.

In 2006 the county’s cluster of bio-pharma and life sciences attracted the Hepatitis B Foundation to establish the Pennsylvania Biotechnology Center in an empty warehouse in Doylestown. Again, the goal was to foster start-up companies. The center operated for its first ten years as a partnership between the Hepatitis B Foundation and Delaware Valley University in Doylestown, whose students gained hands-on experience working in the center’s research labs. In 2016 the university and the foundation parted ways, and the center came under the sole ownership of the Hepatitis B Foundation. Although individual tech companies remained in place for shorter periods than earlier manufacturers, officials in Central Bucks displayed confidence that the industry would continue to be an important source of jobs, even as it went through ups-and-downs. One sign of that confidence was the county’s investment in the Central Bucks campus of Bucks County Community College. In 2017 the Newtown campus added a 43,000-square-foot science building that featured biotechnology laboratories and tissue-culture and instrument rooms.

In Lower Bucks as well, the economy began shifting in the late twentieth century toward high technology companies. After U.S. Steel shut down Fairless Hills in Falls Township, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania designated over a thousand acres at the site as a Keystone Opportunity Improvement Zone (KOIZ). That created tax benefits to persuade companies to locate there. An early arrival was Gamesa Corporation, a Spanish wind energy company that located a manufacturing facility in Fairless Hills, while leasing office space in nearby Trevose for administrative offices. In 2010 Gamesa and Bucks County Community College started a Green Jobs Academy in Bristol to train workers for the green economy. Another milestone of the site was the launch in 2014 of a company called Keystone NAP (short for Network Access Point) to take over the part of the abandoned steel mill containing the electric motors that had run the mill. They converted that electrical heart of Fairless Hills into an advanced data center serving the Northeast Corridor of the U.S. It offered cloud computing and other services to hospitals, insurance, telecommunications, financial services, and other data-intensive businesses.

Postwar Population Growth

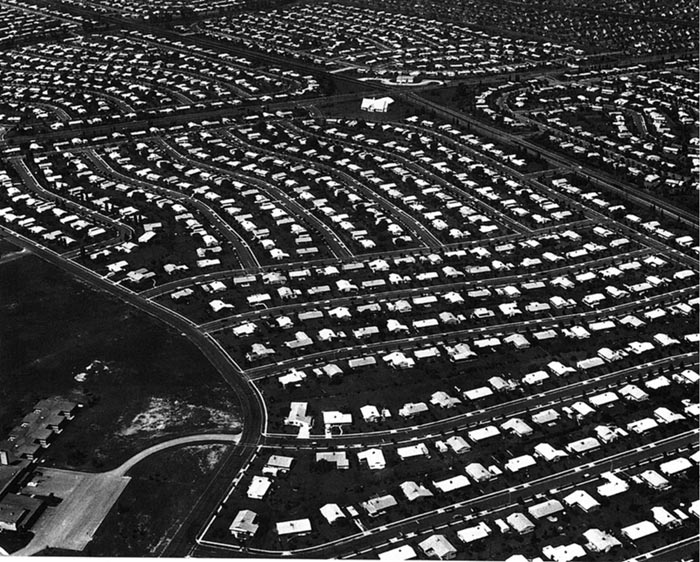

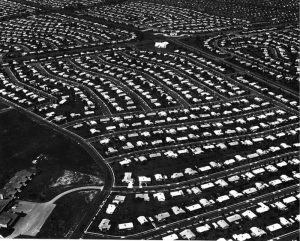

Bucks County experienced its highest percentage growth during the 1950s. The county’s population more than doubled during that decade, a growth rate never equaled before or since. That growth concentrated in Lower Bucks County, spurred by the state’s decision to extend the Pennsylvania Turnpike from Philadelphia eastward to connect with the New Jersey Turnpike. In 1954, the state opened the turnpike from Valley Forge to Bristol, and two years later completed the bridge across the Delaware River into New Jersey. The turnpike exits onto Route 1 serving Bensalem, and Route 13 serving Bristol and Levittown, spawned both industrial parks and housing developments. By far the largest and best-known of the new developments was Levittown, the massive assembly-line suburb built by William Levitt (1907-94). Levittown was so large that it encompassed land in the townships of Bristol, Middletown and Falls, as well as the borough of Tullytown. Buyers snapped up Levitt’s affordable houses priced from $9,000 to $17,500 as soon as they came on the market, and began moving into their homes in June 1952. Eventually, Levittown brought tens of thousands of new residents into Lower Bucks.

By 1980 population growth had shifted upward to Central Bucks. That growth was most pronounced for townships sitting in the path of Route 202. As a very old route crossing the county on a diagonal path, Route 202 enabled suburb-to-suburb commuting that had become popular by the 1970s. The combined population of five townships arrayed along Route 202 in Central Bucks (Solebury, Buckingham, Doylestown Township, New Britain, and Warrington) grew by 60 percent in just two decades between 1980 and 2000.

Contributing to the housing boom in Central Bucks, in the 1970s developers launched a spate of lawsuits against township zoning codes. For example, in 1976 builders sued Buckingham Township and forced a change in zoning that had previously only allowed homebuilding on lots of one acre or larger. That set in motion a rash of lawsuits in other communities, where builders challenged zoning laws as exclusionary, demanding that the municipality “cure” the zoning’s alleged defect and allow the project favored by the builder. Typically, the developers who won lawsuits against overly restrictive zoning codes had little interest in building affordable housing at high density. Instead, they built on quarter-acre or half-acre lots to appeal to middle and upper-middle class households. Merely the threat of a lengthy, costly curative amendment challenge often persuaded municipalities to negotiate with developers. In 1998 one Bucks County coalition labeled curative amendments “the single greatest vehicle for development sprawl” and “nothing more than a way to circumvent our communities’ land use plans.”

Less Development in Upper Bucks

As new subdivisions multiplied in Central Bucks, Upper Bucks remained far less developed. Its rolling hills and farmlands continued to appeal not only to farmers who tended its fields, but also to others who enjoyed its unspoiled beauty. During the 1940s, well-to-do families from Philadelphia and New York had bought land and hired managers to operate their farms, which they dubbed “country estates.” During the 1980s, a new generation of wealthy New Yorkers started buying land and old stone houses to serve as retreats from life in Manhattan. They paid local residents to stock their refrigerators and clean their swimming pools before weekend visits. They had little reason to change the unspoiled landscapes that had drawn them there. The comparatively modest growth in Upper Bucks around the turn of the twenty-first century concentrated mainly around Quakertown in the northwest corner of the county.

As different as they remained, the three sections of Bucks County shared a common demographic pattern: population growth has concentrated in the townships, while the boroughs’ share of the county population has declined. Early residents in the county established boroughs as small, dense settlements carved out of larger townships, often where travelers stopped overnight at inns or taverns. They became the county’s market towns. Since many boroughs were entirely built out by the mid-twentieth century, their housing styles and floor plans did not appeal to suburban buyers in the late twentieth century. Many boroughs had limited space to build large new developments. Whereas in 1970, the boroughs taken together had housed 17 percent of Bucks County’s population, by 2010 they accommodated less than 13 percent. Bristol Borough, which had played such an important role in the county’s history, lost 20 percent of its population from 1970 to 2010. Not all boroughs declined at comparable rates, but overall the boroughs gained a much smaller share of the county’s population growth compared to the townships.

Social Disparities

The early Quakers’ belief in the equality of all people in God’s eyes did not prevent social disparities from emerging. Most significant was the plight of enslaved people in Bucks. Although early settlers mostly employed family members to work their farms, some owned slaves, including William Penn who held slaves at Pennsbury Manor. After the Pennsylvania legislature adopted the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in 1780, slave-holding declined rapidly. The federal census of 1790 counted 261 enslaved persons in Bucks County; by 1810 those records showed only eleven African people remained enslaved in the county.

In 1837 the Bucks County Anti-Slavery Society held its first meeting, focused mainly on eliminating slavery beyond the county borders. Quakers in all three sections of the county took part in the Underground Railroad. Activists often transported runaways to farmlands in Lower Bucks owned by the Philadelphia abolitionist Robert Purvis (1810-98) and his brother Joseph Purvis (1812-57). From there, the escaping Africans rode northward by wagon or stagecoach, sometimes stopping at the Mount Gilead African Methodist Episcopal Church in Central Bucks halfway between Doylestown and New Hope. Other times, they rode all the way to Upper Bucks to the safe house in Quakertown owned by Richard Moore, who in turn sent them up the valley of the Lehigh or the Susquehanna River.

Rather than holding enslaved people, most Bucks County farmers relied on indentured servants whose numbers grew so large that the county set aside a township for them. Early records note a “township allotted for servants” called “Freetown.” That township eventually included parts of East and West Rockhill Townships, and the Boroughs of Perkasie, Sellersville and Telford.

At the opposite end of the social scale were merchants who made fortunes in Philadelphia and built lavish Bucks County estates along the Delaware River. Abraham Bickley III (1731-82), the descendant of a wealthy Quaker shipping merchant, at age 18 inherited the family fortune and in 1754 built Pen Ryn, a spacious and dignified mansion in Bensalem, flanked by formal gardens, stables and barns.

Another example was Andalusia, built in the 1790s by Philadelphia merchant John Craig (1754-1807), who engaged the noted architect Benjamin Latrobe (1764-1820) to design an elegant mansion in Bensalem Township across the border from Philadelphia, naming the estate to reflect Craig’s business as an importer of commercial goods from Spain.

The Grundy Mansion, another overlooking the Delaware River, was originally built to a modest scale in 1818. But William Hulme Grundy (1836-1893), who moved his woolen mill from Philadelphia to Bristol, bought the property in 1884. He spent a year transforming it into a Queen Anne mansion. The property remained in the hands of that prosperous family for more than seventy years until 1961, when it became a house museum for visitors.

Race and Immigration

During the first half of the twentieth century, as working-class families moved into Lower Bucks County for jobs in shipbuilding and other industries along the Delaware River, the population of the area remained overwhelmingly white. After World War II, when the developer William Levitt began building his massive Levittown development for workers at the Fairless Hills steel plant, he deliberately and openly restricted sales to white buyers.

The obvious racial imbalance inspired two important efforts in the early twentieth century to open the housing market to people of color. In the 1920s a white farmer, Frank K. Brown, set aside eighty acres near Route 1 that he named “Linconia” and invited African American families to build homes there. Another racial pioneer, builder Morris Milgram (1916-97), acquired fifty acres near Linconia and in 1954 opened a housing development called Concord Park to attract both Black and white buyers. Over time, the two interracial developments in Bensalem Township blended together to become “Lin-Park.”

Population Gains Through Immigration

Immigrants also contributed to the county’s diversity in the late twentieth century, especially in Lower Bucks. In Bristol, Ukrainian and Russian immigrants arrived in the 1990s. Bensalem and Warminster also took in many new arrivals between 1990 and 2010, including Russians and Eastern Europeans. In those two townships, the large number of immigrant arrivals not only replaced the households who had moved out, but also accounted for all of the population gains registered during those two decades. The 2010 census counted fifty-one thousand foreign-born across Bucks County, with Asians and Hispanics providing the largest numbers of newcomers in the county as a whole.

Despite some active efforts to promote racial inclusion and the noticeable expansion of immigrant communities, in the early twenty-first century Bucks remained the whitest among the Pennsylvania suburban counties outside Philadelphia. In 2010 only 3.6 percent of Bucks County residents were Black in a state with more than 10 percent African Americans. Foreign-born residents made up about 8 percent of the population, the lowest among the suburban counties outside Philadelphia.

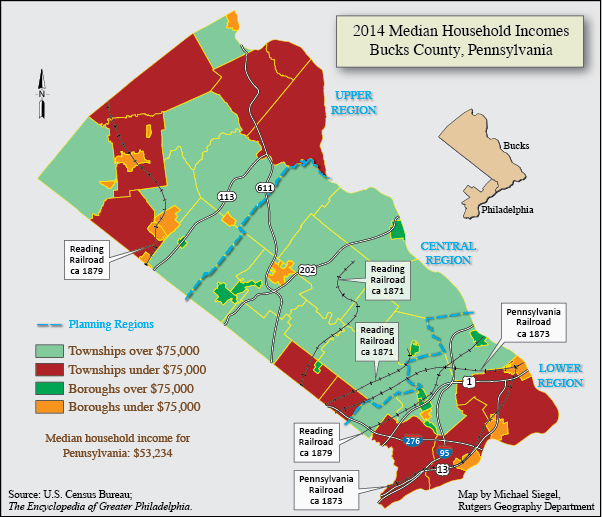

The county’s median household income in 2010 was $70,999. That median figure, however, masked considerable disparities. Working-class families heavily populated older suburbs in Lower Bucks County, partly because they could buy modest houses at lower prices than newer, larger suburban dwellings. The boroughs and townships of Upper Bucks County also tended to be affordable because of the age and styles of their housing stock. In contrast, wealthy townships like Solebury, Upper Makefield, Buckingham, Wrightstown, and Warwick clustered in Central Bucks. There the higher housing prices and household incomes generated greater tax resources to fund municipal services.

Educational Disparities

Among the county’s thirteen school districts, the affluent schools serving New Hope and Solebury Township in Central Bucks spent $26,275 per student in 2015. In comparison, the two school districts serving the Lower Bucks boroughs of Bristol and Morrisville spent about $10,000 less per child. Other low-spending districts could be found in Upper Bucks, particularly Quakertown and Pennridge, two districts that spent less than $17,000 per child. Those inequalities were even more pronounced than the dollar figures portray, considering that lower-spending districts were serving larger shares of low-income children. In the older boroughs of Bristol and Morrisville, two-thirds of school children were eligible for subsidized lunches, compared with only 7 percent of children in the New Hope-Solebury district. Comparisons of local budgets invariably showed that the small boroughs were disadvantaged because their land areas were built out so they cannot easily add new development to enhance their tax base.

Partisan politics reflected the county’s sectional differences. The manufacturing suburbs of Lower Bucks reliably voted Democratic during the post-World War II era. Even in the 2016 presidential election, when pundits expected disaffected white working-class voters across Lower Bucks to support Republican Donald Trump (b. 1946), only Bensalem Township did so. In contrast, the affluent suburbs of Central Bucks, along with the largely agricultural areas of Upper Bucks, leaned Republican. The exceptions to that pattern occurred in the town centers of Central Bucks like Doylestown, Newtown, and New Hope, where Democrats outpolled Republicans.

Sectional Differences in Response to Continuing Growth

In the late twentieth century, Upper Bucks remained less developed and more rural than other parts of the county. In addition to farms, several parks—the largest being Nockamixon State Park—provided large areas of protected open space. Longtime residents watched the development boom in Central Bucks and dreaded the prospect of tract housing, office complexes, shopping centers, and sprawling parking lots advancing northward, swallowing horse farms, woodlands, and wetlands. When pressure increased from developers wanting to build on open parcels, residents mobilized during the 1980s to preserve the green spaces that defined the character of their landscapes.

Starting in 1989, Bucks County began participating in a statewide program to protect agricultural land by acquiring agricultural conservation easements. Together, the county and state governments paid landowners to purchase the development rights on specific parcels. While landowners could subsequently sell that land, the restrictions against development remained in force, guaranteeing that the land would remain in agricultural production. Although the program covered the entire county, it was most active in Upper Bucks, particularly in Bedminster Township, and by 2007 had met its starting goal of protecting ten thousand acres.

While Upper Bucks townships mobilized to slow development, communities in Lower Bucks worked to repurpose industrial lands abandoned by manufacturers that moved away. Brownfield remediation became an important priority for communities trying to convert abandoned industrial areas to new uses. For example, Falls Township promoted industrial re-uses that emphasized green technology, particularly at the abandoned U.S. Steel plant.

In Bristol, local officials sought to repurpose an abandoned airplane plant that later served as a soap factory but completely shut down in the late 1980s. They welcomed an experienced redeveloper of brownfields who bought the forty-three-acre site in 2003 and converted it into offices. In 2015 Bensalem’s leaders launched an ambitious plan to redevelop 675 acres of waterfront property, whose first element was to be a riverside “urban village” called Waterside constructed on a forty-acre brownfield site. In addition to commercial and industrial reuses, builders proposed new residential developments in communities of Lower Bucks, including Bensalem, Lower Makefield, and Middletown Townships, as infill development or redevelopment of abandoned or underutilized sites.

Development Pressure in Central Bucks

The townships in Central Bucks, meanwhile, experienced by far the most intense development pressure. Many residents resisted by opposing proposals for infrastructure—especially highways, sewers, and trash disposal facilities—that would support larger populations. In the mid-1990s when state highway planners proposed converting Route 202 into a four-lane, limited-access expressway between Doylestown and Montgomeryville, Buckingham Township sued in federal court. The lawsuit stalled the project long enough that the state planners offered a lower-impact alternative of a two-lane “parkway” intersected by crossroads at grade level. When that alternative Route 202 Parkway finally opened in 2012, flanked by attractive bicycle and jogging trails, local residents hailed it as a project that met their needs but was unlikely to generate massive levels of new traffic.

Some older boroughs in Central Bucks reacted to the population influx by encouraging developers to build new homes on vacant lots in established neighborhoods—a strategy known as infill development. Doylestown, for example, began working with in-fill developers in the 1990s to bolster the borough’s tax base and to discourage sprawl by keeping development in areas where infrastructure and services already existed. Watching the population age while younger homebuyers favored smaller homes and walkable communities, planners for Newtown, Yardley, and other older Central Bucks communities worked to revitalize their town centers.

While some townships worked to preserve open space, others encouraged new development to reclaim brownfields, while still others tried to steer population and commerce into historic town centers where infrastructure already existed to serve them. Those differing strategies reflected the contrasting sectional identities that marked Bucks County across more than three centuries.

Carolyn T. Adams is Professor Emeritus of Geography and Urban Studies at Temple University and associate editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2018, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Bucks County Atlas, 1876 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Bucks County Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory)

- Edward Hicks (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

- Edward Willis Redfield (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

- Levittown, Pa. Exhibit (State Museum of Pennsylvania)

- "Walking Purchase" of Bucks County Land from Lenni Lenape (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- When Men Were Sold: The Underground Railroad in Bucks County (HathiTrust)

- William Langson Lathrop (Philadelphia Museum of Art)