Camden County, New Jersey

Essay

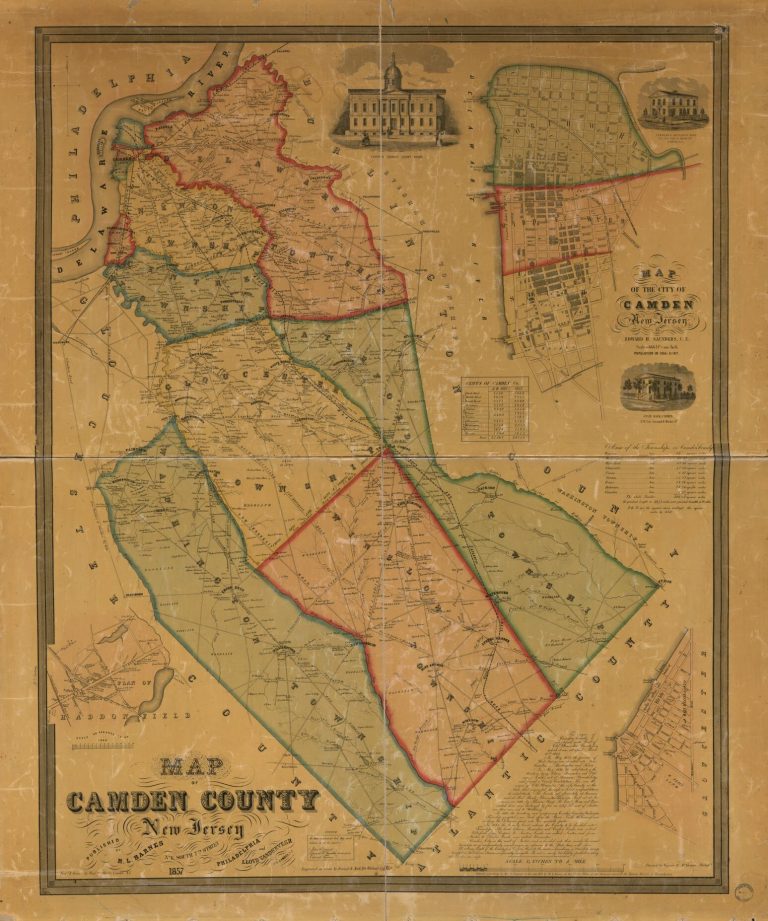

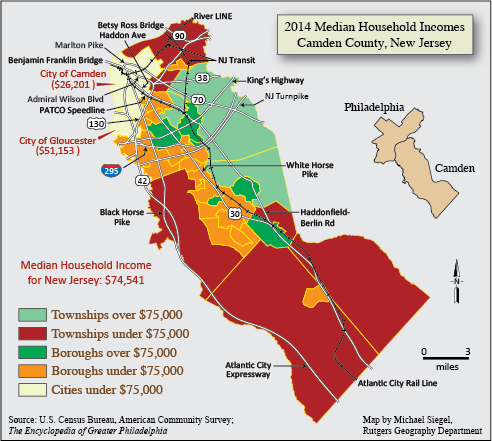

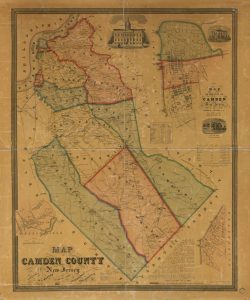

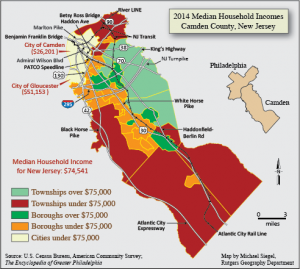

Formed in 1844 from parts of what had been Gloucester County since 1686, Camden County maintained throughout its history a prominent role in the greater Philadelphia region, sustaining its close association with the city of Philadelphia and serving a central role in the social and economic life of South Jersey. Always a diversified area, the county’s more rural areas to the east of Philadelphia suburbanized in the mid-twentieth century even as the county seat and historic county keystone, Camden City, fell in influence and power. By the early twenty-first century, despite considerable effort to reverse the trend, the county reflected every element of the modern balkanized metropolitan area: an impoverished urban core, fraying older suburban areas fringing Camden, and more-affluent outer suburbs.

Early settlement in the area that became Camden County stemmed from European competition to exploit the material resources of the region then designated as West Jersey. Although Swedes and the Dutch settled there first, the desire to be competitive spurred West Jersey’s British trustees, including William Penn (1644-1718), to sign a Concessions and Agreements document in 1677 granting assurances of religious freedom, equitable taxation, and representative government. Aimed at Quakers seeking refuge from persecution, the document induced the settlement of a contingent of migrants from Ireland, in an area known as the Irish Tenth, whose boundaries were contiguous with modern Camden County. Initially coexisting peacefully with native inhabitants, the Lenni Lenape, the European settlers over time displaced native inhabitants as trade and settlement grew in close association with the city of Philadelphia after its establishment in 1682.

A ferry operating as early as 1688 provided the earliest means of communication and transportation between the two colonies on the Delaware River. Operated in its early years by members of the Cooper family, the area of modest settlement on the New Jersey side was known for nearly a century as Cooper’s Ferry. Under Jacob Cooper’s direction, an area of some one hundred acres built up with the intent of making the area Philadelphia’s most prominent suburb. Cooper named his project Camden Town, after Charles Pratt, First Earl of Camden, a British judge known for his defense of the American cause. The effort faltered but did not collapse during the American Revolution, when British troops occupying Philadelphia foraged the area for food and supplies.

Settlement took a big step forward when ambitious entrepreneurs based in Gloucester City laid out city streets in 1820, leading to the incorporation of Camden City in 1828. Early manufacturing plants along the Delaware River boosted the city’s standing and put it in competition with the Gloucester County seat at Woodbury for influence in the region. After rural interests succeeded in carving a new Atlantic County out of the eastern portions of Gloucester County in 1837, Camden enthusiasts pressed their own case for a new county. Divisions hardened, however, as political partisans fought for state as well as local control, and the creation of the new Camden County, finally, in 1844, was bitterly contested. A new courthouse designed by the noted Philadelphia architect Samuel Sloan (1815-84) in 1853 signified the city’s stature, but it was Camden’s emergence as the heart of improved transportation networks, not politics, that explained its rise from a mere hamlet at the time of the Revolution to a city of 9,479, more than a third of the county’s population, at mid-century.

Transportation Networks

A number of entrepreneurs sought to build up rivals to Camden through development expected to follow from the establishment of turnpikes and railways. A number of these enterprises failed, including the Moorestown and Camden Turnpike, chartered in 1849 with the intent of boosting suburban development on the northeastern bank of Cooper’s Creek. More successful was the advent, in 1834, of the Camden and Amboy Railroad with connections to New York City, not just from southern New Jersey but also from Southeast Pennsylvania, for those traveling by ferry to Camden and then north. A second railroad, the Camden and Atlantic, organized in 1836, further enhanced the city as a transportation center, as area residents made their way to the Jersey Shore.

As transportation corridors extended out from Camden at the core, trade picked up in older communities. Originally settled by Quakers seeking religious freedom in 1682, Gloustertown. rose from a tiny fishing village to become the center of local political and military organization in the years immediately before the American Revolution. Early manufacturing activity there was promising, but lack of a rail connections to Camden, until 1873, retarded growth, despite the area’s incorporation as Gloucester City in 1868. With that rail connection in place, the city grew by nearly 50 percent in the ensuing decade to 5,347 people. The area north of Camden also flourished with gristmills and sawmills established along the Pennsauken Creek in an area designated as Delaware Township. In 1854 a group of investors, seeking to capitalize on a proposed rail line passing through a cluster of country estates owned by Philadelphia dry goods merchants and known locally as Merchantville, laid out additional lots intended to spur growth. With the arrival of the Camden and Amboy in 1869 they realized returns on their investments, and in 1874 the tiny hamlet—at seven-tenths of a square mile—officially formed as Merchantville Borough, separating itself from Stockton Township, which had itself formed out of the north portion of Delaware Township in 1859. In 1892 another portion of Stockton, which had fostered its own industries, withdrew to form Pennsauken Township. Finally, in 1899 the city of Camden annexed the remaining part of what had once been Stockton Township.

Camden County grew steadily throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, rising fourfold from a population of 25,422 in 1850 to 107,643 in 1900. Even as rail connections prompted town growth along the Delaware River, railroads boosted suburban development to the east. The Camden and Atlantic line’s decision to locate a stop and telegraph station on Collins Farm Road in 1871 prompted local residents six years later to incorporate as Collingswood. Spurred by investments, including the creation of the 61-acre Knight Park, by Philadelphia import-export merchant and sugar refiner Edward Collings Knight (1813-92) and other Collings family members, the area realized its aspirations to form a desirable residential enclave. Describing itself as supporting “the clean, pure life essential to social advancement,” Collingswood was one of the first communities in New Jersey to elect to go dry under 1873 legislation that provided the local option to do so. Just to the east, Haddonfield, whose incorporation stretched back to 1701 and whose early history included the New Jersey legislature’s adoption of the state seal at the Indian King Tavern in 1777, also grew as a result of the arrival of the rail connection between Camden and Atlantic City that materialized in 1853. After investors with connections both to turnpikes and rail lines formed the Haddonfield Improvement Company to market building lots in the area, Haddonfield grew sufficiently to break away from Haddon Township to form its own borough, in 1875. Farther along the Camden and Atlantic City line, rail officials opened a station at Long-A-Coming, derived from the name used by Native Americans who used the Lonaconing Trail to describe the route that connected the Jersey Shore to the Delaware River. As the area grew, it assumed the new name of Berlin, not because it drew settlers from Germany, although Germans were among the railroad’s directors, but as a community specifically created for Philadelphia Germans seeking to escape nativist attacks.

The opening of the Delaware River (subsequently named Benjamin Franklin) Bridge in 1926 scrambled established transportation patterns for the region, forcing the Reading and Pennsylvania Railroads to consolidate their once highly competitive rail connections between Camden and the Jersey Shore and spurring greater reliance on automobiles for travel. A grand boulevard connecting to the bridge, designed in the City Beautiful style and named in 1929 to honor Rear Admiral Henry Braid Wilson (1861-1954), a Camden native who served in the Spanish-American and First World Wars, was intended to bind Camden City to surrounding towns, even prompting the idea of consolidating city and suburbs. Such hopes were quickly dashed by established nearby towns protective of their independence, and outward movement of settlement as well as traffic remained modest through the Depression and war years. Indeed, it was largely the undeveloped character of Delaware Township, which hugged the extension of the Admiral Wilson, the Marlton Pike (Route 70), that drew investments for regional destinations. The Garden State Race Track, opened during World War II on previously foreclosed land, prompted a number of additional glitzy entertainment venues, including the Cherry Hill Inn on farmland purchased by the banker and racetrack owner Eugene Mori (1898-1975) and the luxurious Rickshaw Inn opposite the racetrack’s main entry gate on Route 70, a local landmark marked by its plate-gold roof and Asian decor.

Employment Expands to the Suburbs

Until the mid-1950s, much of Delaware Township remained farmland, with the exception of a grouping of fine brick homes with generously proportioned lots and streets named for elite suburbs on Philadelphia’s legendary Main Line in the town’s Colwick section. That changed in the mid-1950s, as developers carved out new neighborhoods laced with tract housing in much of the 24-square-mile township. The location of a new RCA electronics plant on a ridge known as Cherry Hill, on land sold by Mori as he sought tax relief, brought newcomers to the area, many of them engineers from New York, even as it marked a shift of resources out of Camden. Even more important, again at Eugene Mori’s instigation, the first enclosed regional mall on the East Coast opened on October 11, 1961. Designed by shopping center pioneer Victor Gruen (1903-80) and developed by James Rouse (1914-96), the Cherry Hill Mall was not responsible for the choice of the new name given the township the same year, but it helped establish Cherry Hill as a central destination for all county residents. By 1965, Cherry Hill’s assessed property value, up from $9.5 million in 1950 to $156.2 million, exceeded that of Camden, making it the richest community in the county and all of South Jersey.

Employment opportunities outside Camden also grew in Pennsauken, which boasted the region’s busiest airport during the 1930s, until larger planes required longer runways and air travel shifted to Philadelphia. Both before and after World War II, Pennsauken attracted companies like Kieckhefer Container, which established its business at what had once been a yacht club on the Delaware River, employing some six hundred workers throughout the 1930s, and Randall Manufacturing, the makers of plumbers’ enamelware, hired another five hundred. Nearby, Cities Service established refining facilities covering most of Petty’s Island. After the war, Pennsauken attracted a host of midsize companies to a newly established industrial park on the Delaware waterfront. Between 1958 and 1970 manufacturing jobs in Camden County outside the city increased from 6,184 to 21,316, a number on a par with Camden itself. Even as the city lost close to half its manufacturing base in the 1960s, suburban manufacturing employment increased at a rate of 85 percent.

Population Growth

Blessed with an array of housing options and employment opportunities, the suburbs boomed in the mid-1960s and afterwards. With a population of 255,727 in 1940, Camden County climbed to 392,035 twenty years later. It added another 64,000 people over the next decade, when growth slowed considerably. As Irish, Italian, and other white ethnic families made the transition from factory work to white-collar occupations in Philadelphia and Camden, they moved to new homes aimed at a burgeoning suburban middle class. In a conscious effort to protect the newly acquired benefits of suburban life, these towns introduced building restrictions, through practices that came to be called exclusionary zoning. In Delaware Township, Mayor Christian Weber and his colleagues altered the township’s zoning code to require larger lots, as Weber asserted, “there will be no row houses, twin houses or prefabricated homes in the township.” Similarly, Collingswood placed controls on garden apartments with the clear intention of keeping out renters who might prove a tax burden to the township.

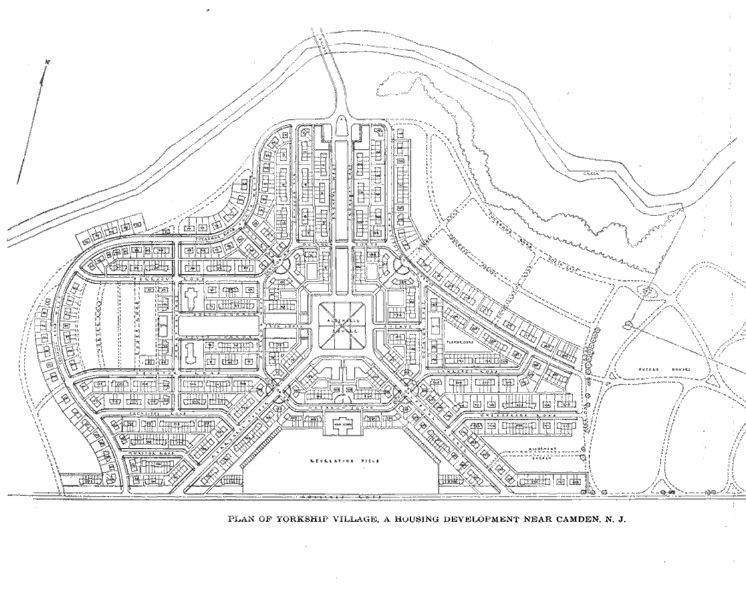

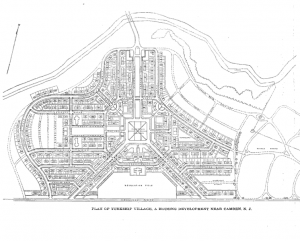

Due to its close proximity to shipbuilding facilities on both sides of the Delaware River, Camden County became home to several distinctive planned communities during World Wars I and II. Seeking to alleviate a severe shortage of housing options for ship workers employed at Camden’s New York Ship facility, the U.S. Shipping Board’s Emergency Fleet Corporation designated 225 acres of farmland at the eastern edge of Camden to accommodate 1,400 new housing units. Laid out according to “Garden City” principles established by Ebenezer Howard (1850-1928) in England in the early twentieth century, the new community allocated generous amounts of open space, including a central town square lined with shops, to support modest homes sited close to public ways with the intent of enhancing sociability among workers. Known originally as Yorkship Village, the area was annexed into Camden after World War I and subsequently became known as Fairview.

Several decades later, as another war approached, area planners utilized a new version of a planned community for war workers by laying out Audubon Park. Composed of some five hundred prefabricated units and supported by Camden #1, the Industrial Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers of America, Audubon Park operated according to a pioneer “mutual plan” under which residents bought shares in the mutual benefit company that owned the land. Designed by the prominent Philadelphia-based architect Oscar Stonorov (1905-70), who had been codesigner of Yorkship Village, Audubon Park combined elements of city density with easy access to the amenities of suburban life. Such could also be said of the second mutual home development in Camden County, Bellmawr Park, some five hundred units carved out of an estate dating back to the seventeenth century. Both projects were meant to house war workers with construction costs being provided by the federal government’s Works Progress Administration.

Historically, African Americans had lived throughout the county: in pockets of Camden, in an area of Cherry Hill known as Batesville separated from other settlements by a country road, in Haddonfield just off of the Haddonfield-Berlin Road, in Chesilhurst, and most visibly in the historically Black town of Lawnside (originally known as Free Haven, then Snowhill when it was closely associated with Underground Railroad activity). Laid out initially in 1840 by Haddonfield Quaker and abolitionist Ralph Smith, the area offered small lots to free Black people at low cost. Incorporated in 1926, Lawnside became widely known as a rich source of Black entertainment for the region as well as a thriving community of upwardly mobile residents.

Elsewhere, zoning restrictions, often combined with overt hostility, blocked Camden’s African American population, which reached a majority in the decade following civil disturbances that erupted in the city in 1971, from accessing homes in the suburbs. Housing choices in the 1970s and beyond thus became racially skewed in spite of the national fair housing legislation adopted in 1968. Spurred by discrimination in housing in Mount Laurel, just across the Camden County line in Burlington County, lawyers for plaintiffs seeking a zoning change to allow multiple-unit construction achieved a state supreme court ruling that every community should make available its “fair share” of affordable housing. While the ruling anticipated opening the suburbs to a broader class of residents, executing it proved difficult. Forty years after the first Mount Laurel ruling, Camden still had four times its share of affordable housing, while nearby communities Cherry Hill, Pennsauken, and Haddonfield fell well short of fulfilling their obligations.

Over time, suburban development shifted even farther east and away from Camden, a pattern evidenced especially in Voorhees, which came to be perceived as more exclusive than the once-premier destination of Cherry Hill. A town of just some 6,000 in 1970, Voorhees boomed following the opening in 1970 of the Echelon Mall, doubling its population the next decade and reaching a population of 28,000 by 2000, after which growth slowed considerably. Some former Camden residents who had settled along bus lines in nearby Pennsauken or the western portion of Cherry Hill in the 1960s chose to move farther out. As one sign of such decisions, the Beth El synagogue, which traced its origins as Camden’s first conservative congregation to 1920, moved first to Cherry Hill in 1967 and subsequently to Voorhees in 2009.

To the far east, Winslow Township, the largest jurisdiction in the county at fifty-eight square miles remained largely farm country for its eleven thousand residents as late as 1970. Nestled at the edge of the Pine Barrens, where environmental restrictions circumscribed growth, the township exploded in the 1980s as developers cleared land for larger, ex-urban homes that had come into demand. The area added another ten thousand residents each in the 1970s and 1980s, achieving a population of just under forty thousand in 2010. Connected both to the shore communities by the Atlantic City Expressway and other population centers to the north through Routes 30 and 73, Winslow offered a rare combination of easy access to employment as well as premier recreational and entertainment facilities.

Social Disparities

Outward movement from Camden continued in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries as Black and Hispanic families followed the pattern of earlier outmigration, to the west sides of Cherry Hill and Collingswood and especially to Pennsauken. As the minority population grew there, and with it the number of children eligible for free school lunches, local residents seeking to incorporate newcomers while still hoping to moderate the pace of racial turnover persuaded town officials to establish a Stable Integration Review Board. Formed in the mid-1990s with the purpose of encouraging white residents to buy homes and stay put, the initiative drew support of both Black and white residents. The effort, which lasted more than a decade, had limited effect, as by 2015 the white population had fallen from 55 percent in 2000 to under 20 percent. Meanwhile, the African American population increased to 33 percent and Hispanic to 49 percent.

As Camden County made the transition into the twenty-first century, it witnessed a number of initiatives aimed at achieving more balanced growth. When New Jersey took the extraordinary step of assuming day-to-day control of the city of Camden for seven years starting in 2002, it required the formation of a regional impact council aimed at stemming the spread out of Camden of problems such as crime and blight, while offering hope that the difficult issues of affordable housing might be taken up on a regional basis. Local officials only reluctantly formed a council composed of the mayors of nearby jurisdictions two years after it was mandated, and they failed to pursue its stated goals with any rigor. As a result, efforts to diversify the housing stock of communities outside Camden proceeded largely as a result of the threat if not actual exercise of court actions. More hopefully, Collingswood invested in multiunit developments near the PATCO Speedline into Philadelphia, thereby fulfilling the smart growth goals behind such transit planning. An effort to convert the deserted race track in Cherry Hill into a compact town center linking homes and apartments to shopping along Garden City ideals proved less successful, as resulting development created largely big box retail well beyond walking distance of residential construction.

As of 2010 Camden County’s relatively diverse population had reached 513,657: 65 percent white, 20 percent African American, 14 percent Hispanic, and 5 percent Asian. The city of Camden remained the county’s largest entity, at 77,344, with Cherry Hill not far behind at 71, 045. Eighty-eight percent of county residents had completed high school, while more than 30 percent held a bachelor’s degree or higher.

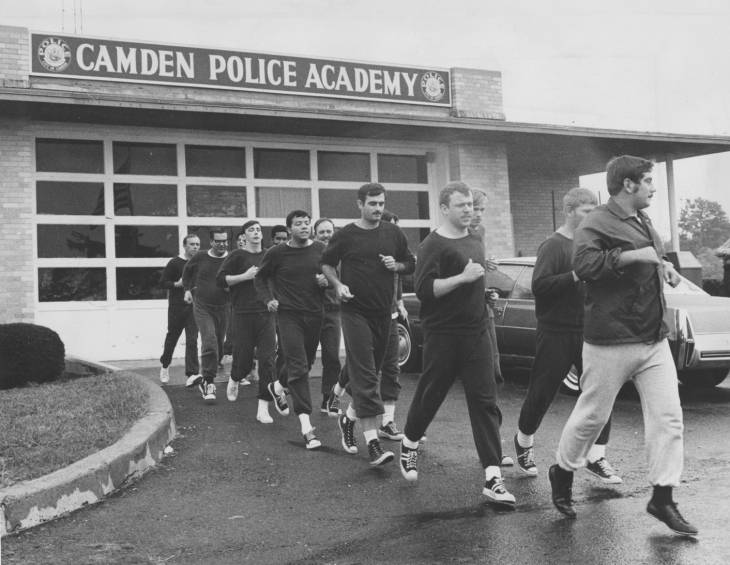

In its modern form, Camden County proved reliably Democratic, as evidenced by complete control of its chief county agency, the Board of Chosen Freeholders. A holdover from the colonial era, the Freeholders advanced some modern concepts, taking over the function of policing Camden in 2012 and advancing an ambitious building program through the Camden County Improvement Authority, including hospital and university construction projects and highway improvements. Figures associated with county politics, most notably South Jersey’s most prominent political broker, George Norcross (b. 1956), and his brother Donald (b. 1958), a state senator and subsequently Camden County’s congressional representative, parlayed a generous state incentives program to relocate businesses from different parts of the county into Camden. Facilitated by Republican governor Chris Christie (b. 1962), the reinvestment program did not immediately alter the high level of poverty in Camden, but it nonetheless altered Camden’s image as well as its skyline as a city rising. With affordable housing still largely concentrated in Camden, no one predicted a reversal of population outmigration from the city any time soon, leaving Camden County still racially and socially divided.

Howard Gillette Jr. is Professor Emeritus of History at Rutgers University-Camden and co-editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University