Civil Rights (African American)

By James Wolfinger and Stanley Keith Arnold | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Black Philadelphians have fought for civil rights since the nineteenth century and even before. Early demands focused on the abolition of slavery and desegregation of public accommodations. The movement gained greater power as the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth and the World War I-era Great Migration brought tens of thousands of African Americans to the Philadelphia region. This exponential growth in the African American population gave Black Philadelphians the numbers and resources necessary to effect political change. Such efforts were never limited to the ballot box, access to which had been legally gained by constitutional amendment, but were instead linked to community needs for adequate housing, economic opportunity, and social and educational services. As African Americans gained greater rights, especially in the post-World War II period, Black Philadelphians shifted more to emphasizing the need to achieve results based on their legal equality. The struggle to maintain civil rights and translate those rights into concrete results extended beyond the classic period of the 1960s and continued to shape Philadelphia into the twenty-first century.

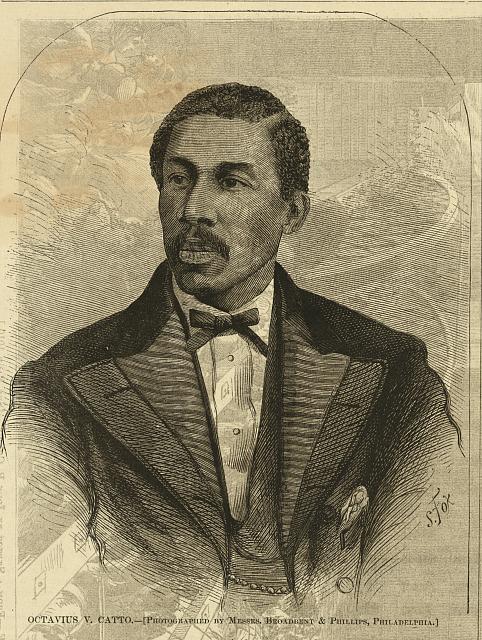

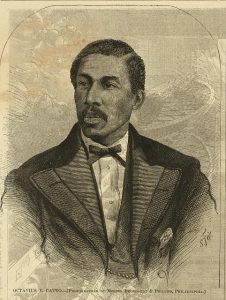

Civil rights activists in the nineteenth century focused on the abolition of slavery, securing voting rights, and gaining equal access to public accommodations. Richard Allen (1760-1831), who was born into slavery and became a prominent minister, founded the Free African Society that pushed for the abolition of slavery. Octavius Catto (1839-71) helped raise troops to fight in the Civil War and afterward led the campaign for voting rights, until he was assassinated while trying to exercise the franchise in 1871. Catto also worked with William Still (1821-1902) to desegregate the city’s streetcars, which led the Pennsylvania state legislature to pass a law in 1867 requiring streetcar companies to carry passengers regardless of color. Such activism helped lead to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which declared African Americans were entitled to equal treatment in public accommodations. Reverend Fields Cook (1817-97) tested the law and won a case against Philadelphia’s Bingham House Hotel when he was denied a room in 1876.

The civil rights movement gained greater momentum in the early twentieth century with the Great Migration. The Black population in Philadelphia surged from some 63,000 in 1900 to over 134,000 twenty years later. New arrivals lent their energy to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the National Urban League, and the city’s Black newspaper, the Philadelphia Tribune, (published by E. Washington Rhodes [1895-1970], established 1884). Through these organizations, they demanded greater access to jobs and adequate housing. Yet a brutal race riot over housing desegregation in 1918 that left two people dead and dozens injured demonstrated that Philadelphia was not the land of hope that many prayed they had found.

Expanding Residential Access

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, African Americans deepened their commitment to securing civil rights. In the 1920s, they expanded their access to residential areas in North, South, and West Philadelphia. They also supported a flowering of Black culture with authors such as Jessie Redmon Fauset (1882-1961) from Fredricksville in Camden County, New Jersey, and venues such as the Dunbar Theater at Broad and Lombard in Philadelphia, giving Philadelphia a smaller version of the Harlem Renaissance. The Great Depression devastated African American efforts to secure more housing and create a vibrant community, and in the process, radicalized Black political activism. In the early 1930s, African American unemployment crested at 61 percent, and tens of thousands of people lost their homes. In response, Black Philadelphians joined the Democratic Party, the National Negro Congress, and the Communist Party. They engaged in “Don’t buy where you can’t work” campaigns to pressure employers to end discrimination. And they demanded that political leaders meet a number of pressing needs: public housing to make up for the lack of decent and affordable housing, access to government-funded jobs, and an Equal Rights Bill (passed by the state legislature in 1935) to once again guarantee access to public accommodations.

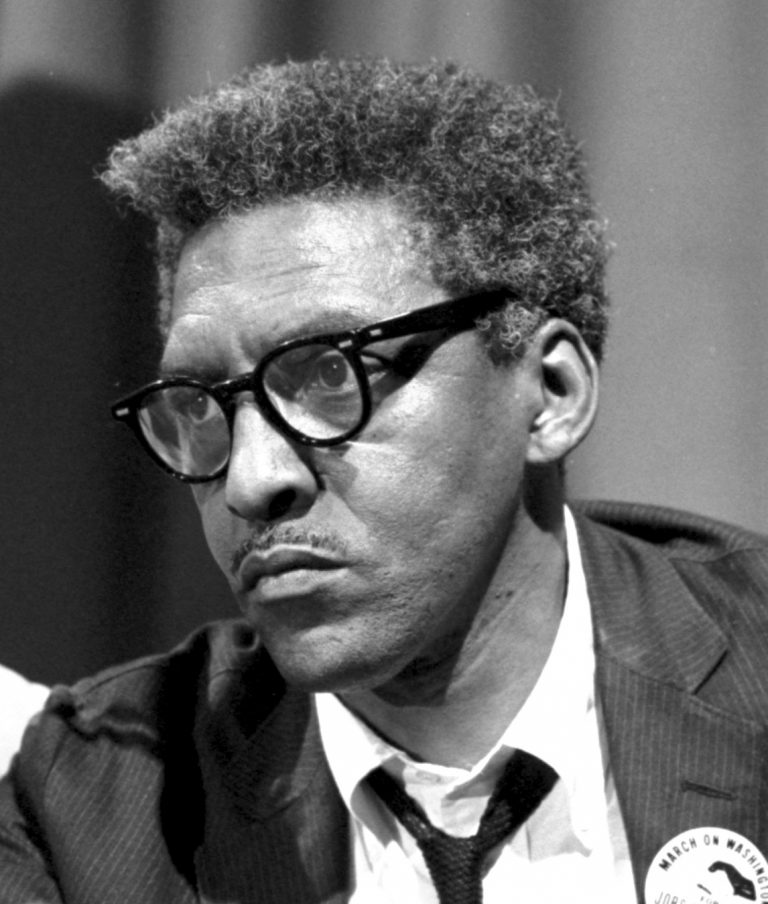

Demands for civil rights in the area of jobs, housing, and political recognition continued into World War II. As the federal government poured billions of dollars into Philadelphia industries, African Americans flocked to the city. The Black population grew from some 250,000 in 1940 to 376,000 by the end of the war decade, and many of these residents supported the national Double V campaign that called for victory over fascism abroad and over Jim Crow at home. A presidential executive order, prompted by A. Philip Randolph’s (1889-1979) March on Washington Movement, prohibited discrimination in hiring at industries receiving defense contracts and was a reminder that the federal government could be an ally in pushing for civil rights. Nonetheless, many companies tried to maintain a segmented system that confined Black workers to specific jobs. Employment practices at the Philadelphia Transportation Company, for example, led to a campaign promoted by the NAACP and its leader Carolyn D. Moore (1916-1998) (who had started in the organization in Norristown, Pennsylvania) to secure driving jobs for African Americans. When the federal government ordered the desegregation of the workforce in August 1944, white workers staged one of the largest hate strikes of World War II, shutting down the city for nearly a week. African Americans also had to continue their struggle in the city’s neighborhoods, where redlining and other discriminatory loan policies restricted African Americans to the most dilapidated communities. Federal Housing Administration policies as well as violence perpetrated by some white Philadelphians kept new public housing segregated as well.

The experience of World War II transformed civil rights in Philadelphia as the concerted efforts of the NAACP and local interracial organizations energized the Black community. Although there were fears that interracial strife would grow after the war, a strong economy and the diligence of the civil rights community prevented the rise of racial violence. Economic concerns took particular precedence in this era, as African Americans who had been hired in defense-related industries feared they would lose their jobs. Civil rights activists such as the Reverend E. Luther Cunningham (1909-1964) seized the moment and in 1948 secured passage of a municipal Fair Employment Practices ordinance that the state later adopted in similar form. New Jersey already had such a law on the books (passed in 1945), and Delaware added its own version of the law in 1960. Black Philadelphians also helped elect Democrat Joseph Clark (1901-90) as mayor in 1951, which cemented the political reorientation of the city and led to the implementation of the Home Rule Charter that provided for a Commission on Human Relations, one of the first agencies in the nation dedicated to preventing discrimination.

Decades of Job Losses

Although the new Democratic administration paid greater attention to African American rights and increased civil service opportunities, deindustrialization and persistent housing segregation showed the need for continued civil rights agitation. Philadelphia lost some 250,000 industrial jobs between the 1950s and the 1980s, and as workplace opportunities evaporated many African Americans were disproportionately affected because they could not follow the jobs to the suburbs. Many white Philadelphians moved to suburban developments such as Levittown, Pennsylvania. Suburbanization freed up housing stock for some middle-class Black residents to move into city neighborhoods that had previously been off limits, but racist lending practices and white violence meant most suburban housing excluded Black settlement. In 1957, a race riot broke out when white homeowners protested the arrival of the Myers family in Levittown.

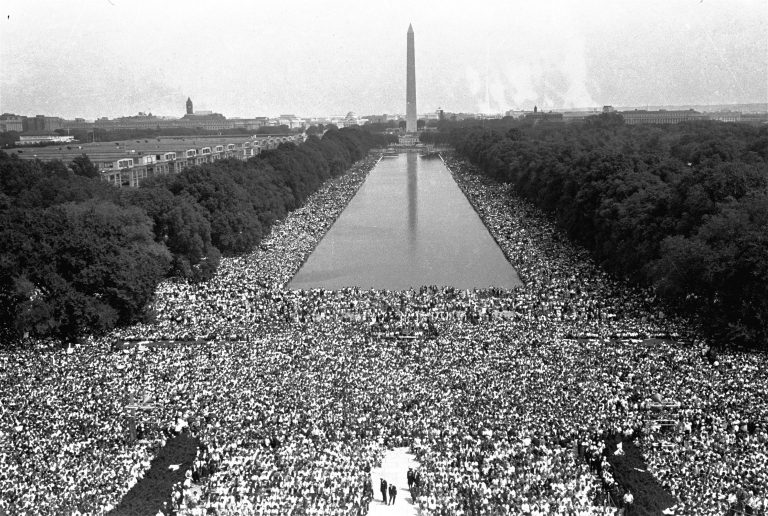

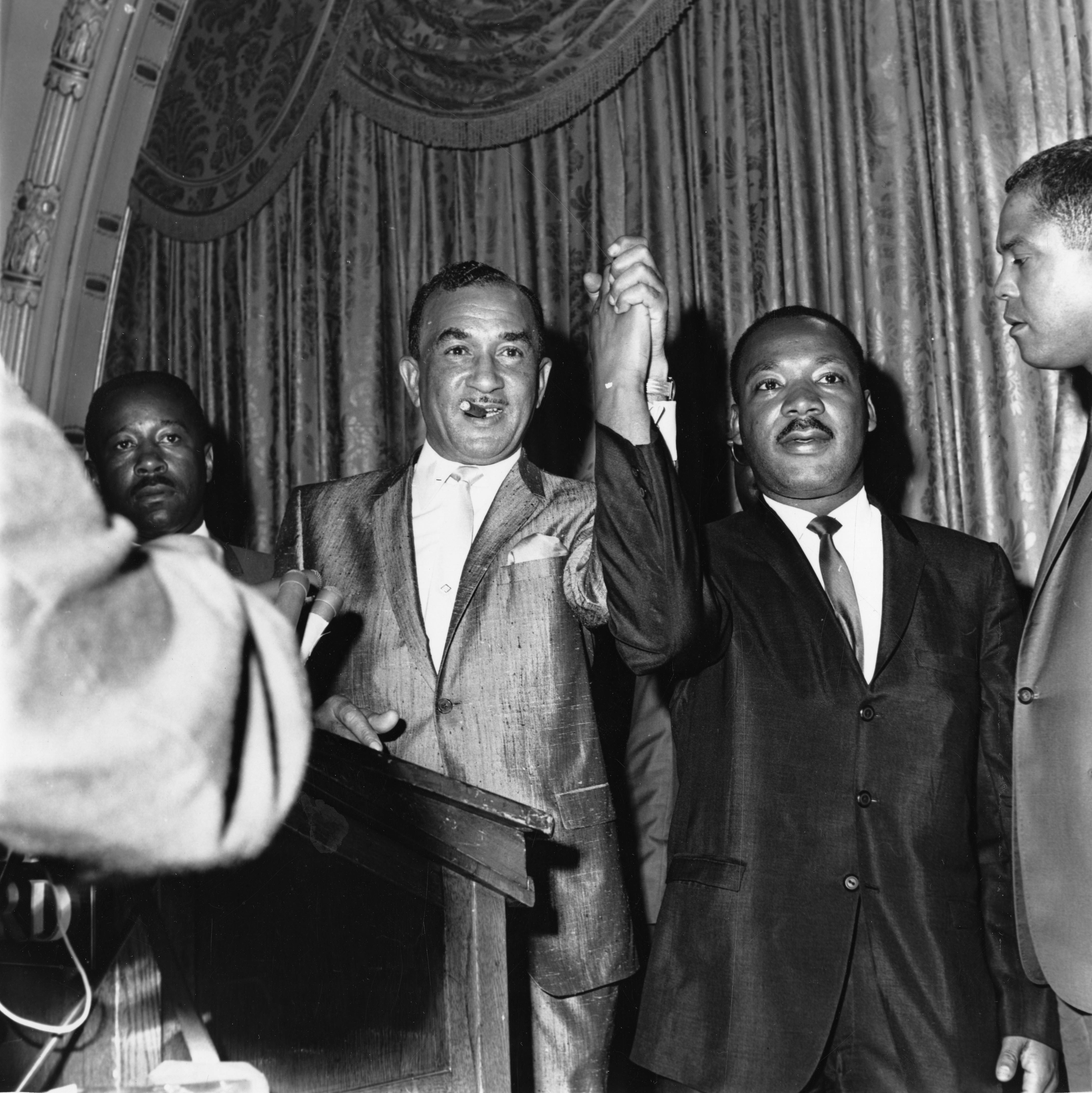

White intransigence sharpened Black Philadelphians’ commitment to a civil rights movement that transformed Philadelphia in the 1960s. Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929-68) had been introduced to Satyagraha (Mahatma Gandhi’s movement based on passive political resistance) at Philadelphia’s Fellowship House, an interracial organization in the late 1940s. King studied at Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, and lived in Camden, New Jersey, from 1949 to 1951. As a result, King was well acquainted with Philadelphia’s civil rights community. Local civil rights activists provided moral and material support to King, who visited the city several times in the 1960s. Inspired by the national movement, local civil rights leaders such as the Reverend Leon Sullivan (1922-2001) and NAACP branch president Cecil B. Moore employed new tactics. In 1960, Sullivan and other Black ministers launched a boycott of Tasty Baking Company, one of the city’s largest businesses, over its refusal to hire Black workers. The success of the boycott influenced Moore to initiate street protests against racial discrimination in the construction industry and in food markets that did not hire Black employees. This activism drew greater power with the passage of federal affirmative action legislation and found support from white allies in the Northern Student Movement, Fellowship House, and other area organizations.

While increasing protests contributed to a rising level of consciousness among Black Philadelphians, they were unable to stem the tide of frustration in the city’s poorest communities, especially in North Philadelphia. In the early 1960s, North Philadelphia had the city’s highest poverty and unemployment rates and tense relations with the police. On August 28, 1964, rioting broke out after an altercation between two Black motorists and two police officers. Hundreds were arrested and injured, and the uprising indicated the emergence of a new militancy among many Black Philadelphians. Some activists turned to more militant organizations such as the Nation of Islam, the Black Panthers, and the Black People’s Unity Movement in Camden. Although the Philadelphia area had a long history of interracial civil rights organizing, an increasing number of activists influenced by Black Power ideology criticized the role of whites in the movement.

The Black Power Movement

By the late 1960s, the Black Power movement had significant influence in the civil rights community. Both traditional civil rights activists and younger Black militants coalesced around the issue of education. Thousands protested the exclusion of African Americans from an all-white private school, Girard College, located in North Philadelphia. The movement against educational racism involved parents (mainly African American women), educators, and students. In addition to enduring inferior schools, Black students criticized dress codes that excluded traditional African garb and demanded a curriculum that included Black history. In late 1967, Black students launched a major protest at Board of Education headquarters and were attacked by police. The clash exemplified persistent tensions between the Black community and the police.

While street protests continued in the late 1960s, an increasing number of civil rights activists sought public office. Buoyed by the passage of significant federal civil rights legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968, these activists believed that they could considerably influence the political process. C. Delores Tucker (1927-2005) became the first Black Pennsylvanian appointed to the office of secretary of state. David P. Richardson (1948-1995) was elected to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives in 1972. In 1984, W. Wilson Goode (b. 1938) became Philadelphia’s first Black mayor. Although this new generation of political leaders had its roots in activism, their different power bases reflected an increasing maturation of the movement. Tucker had been active in the mainstream civil rights struggle and the rapidly emerging feminist movement. Richardson began his activism as a community organizer, while Goode’s rise was propelled by his support among the city’s Black religious establishment. Goode’s success was in part fueled by the work of the city’s first Black deputy mayor, Charles W. Bowser (1930-2010), who had run unsuccessfully for mayor in the 1970s. In turn, Goode’s administration paved the way for future Black mayors John Street (b. 1943) and Michael Nutter (b. 1957). While Black officials took power at a more formal level, a growing number of community based organizations recognized the limits of their offices. The Kensington Welfare Rights Union, for example, articulated the demands of poor and working-class people of all races beyond what was provided in legislation.

Although the election of President Barack Obama (b. 1961) demonstrated the gains made by civil rights activists, Black Philadelphians recognized the many problems they still faced. In the 2000s, Philadelphia’s civil rights movement witnessed the emergence of organizations that addressed crime, joblessness, education, and immigration among other issues. In all, the changing demographics and economic environment of the Philadelphia region represented new challenges and extensions of old ones for the next generation of civil rights activists. Yet despite these challenges, the history of Philadelphia’s civil rights movement demonstrated the gains African Americans made.

James Wolfinger is Professor of History and Education at DePaul University. He is the author of Philadelphia Divided: Race and Politics in the City of Brotherly Love and Running the Rails: Capital and Labor in the Philadelphia Transit Industry. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Stanley Keith Arnold is associate professor of history at Northern Illinois University. He is the author of Building the Beloved Community: Philadelphia Interracial Civil Rights Organizations and Race Relations, 1930-1970. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Girard College names interim president (WHYY, June 8, 2012)

- Black History Month youth essay contest doubles as way to honor Germantown's 'Unsung Heroes' (WHYY, February 17, 2014)

- Thousands march to 'Reclaim MLK' in Philly (WHYY, January 19, 2015)

- Activists relate to King's shift from dreamer to radical (WHYY, January 16, 2017)

Links

- Civil Rights in a Northern City (Temple University)

- Civil Rights Resources (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Civil Rights: A Movement is Born in Philadelphia (Philadelphia: The Great Experiment)

- African American Museum in Philadelphia

- Philadelphia Tribune

- Octavius Catto Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

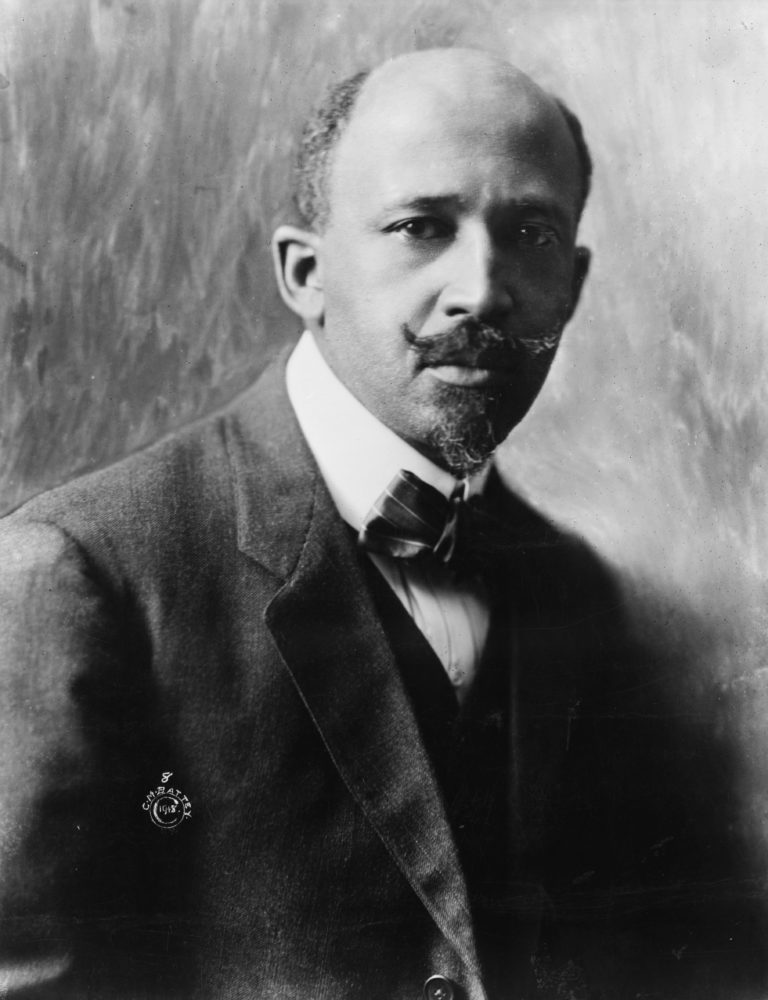

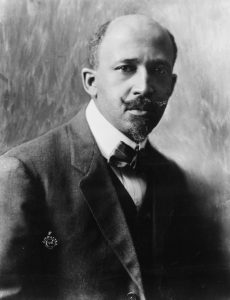

- Legacy of Courage: W.E.B. DuBois and the Philadelphia Negro

- African American Baseball in Philadelphia Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)