Rock and Roll (Early Years)

Essay

For most Americans in the mid-1950s, rock and roll seemed to come out of nowhere, a raucous new musical style that suddenly burst on the scene. In reality, rock and roll had been taking shape for decades, as uniquely American vernacular musical styles such as jazz, blues, gospel, and country music cross-pollinated. The process unfolded in urban as well as rural settings, in both Black and white communities. Mostly, it took place out of the mainstream of popular culture until the mid-1950s, when the new music took the pop music world by storm. The first national hit records featuring the blending of country music and rhythm and blues—the essence of early rock and roll—came out of Philadelphia in 1953 and 1954.

Philadelphia was well positioned to play a leading role in popular music. The city had long been one of the nation’s most important musical centers, with strong traditions in both European-derived and African American music dating back to the eighteenth century. In the early twentieth century Philadelphia saw a dramatic increase in its Black population as a result of the Great Migration. By the 1940s, Philadelphia’s large and diverse Black population had created thriving scenes in jazz and gospel music. From these traditions a new kind of music emerged in the 1940s, in Philadelphia and across the nation. Usually played in small combos called “jump” bands, the music featured rollicking dance rhythms coupled with fairly simple blues-based harmonies and melodies. The adaptation of this style, known as “rhythm and blues” or “R&B,” by white musicians essentially created rock and roll.

In Philadelphia in the late 1940s and early 1950s, jump bands played dance halls, nightclubs, and corner bars in Black neighborhoods throughout the city. The better groups also toured and got record deals. Two such bands were Jimmy Preston (1913–84) and His Prestonians and Chris Powell (1921–70) and His Blue Flames. In 1949 both the Preston and Powell groups recorded a song called “Rock The Joint,” a spirited tune that rock historians consider a seminal recording in the emergence of rock and roll. Like most R&B music of the time, the records were targeted to a primarily African American audience. It was not until a white Philadelphia-area country-and-western group adapted “Rock The Joint,” along with other R&B numbers, that Americans at large took notice.

Bill Haley (1925–81), from Boothwyn, near the city of Chester, was a country- and-western musician heavily influenced by the Western Swing style, particularly the music of Bob Wills (1905–75) & His Texas Playboys. Haley’s group, The Saddlemen, played throughout southeastern Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey in the late 1940s. Haley also worked as a DJ at Chester radio station WPWA, which often featured his group. The Saddlemen developed a following and began to make records for local labels in the late 1940s. These recordings were firmly in the country-and-western tradition, but around 1951 Haley began to introduce elements of R&B into the group’s live performances. Audiences responded very positively and over the next few years the group transitioned to a new hybrid style, later dubbed “rock and roll.” In came instruments like drums and saxophone and out went the cowboy hats and the name “The Saddlemen.” The group became “Bill Haley and His Comets.”

In the spring of 1952 Haley’s group recorded a version of “Rock The Joint” for the Philadelphia-based Palda label, later renamed Essex. The record received a lot of radio play, mostly in the Northeast. Other R&B-flavored recordings followed, including Haley’s composition “Crazy Man Crazy.” Released in April 1953, “Crazy Man Crazy” became a national hit, one of the first songs to introduce mainstream America to rock and roll. Bill Haley and His Comets then moved to Decca Records, a major label, where they had even greater success. In May 1954 Decca released their tune “Rock Around the Clock,” but it did not sell very well. That summer, however, their cover of the R&B tune “Shake, Rattle & Roll” became a huge hit. Then “Rock Around the Clock” was featured prominently in Blackboard Jungle, a movie about juvenile delinquency that caused quite a stir when released in early 1955. “Rock Around the Clock” became a massive hit, the teenage anthem of the age. It sold millions of copies and stayed on the pop charts for months, making Bill Haley and His Comets worldwide stars. Their popularity continued with the 1956 release of the movie Rock Around the Clock, which featured lip-synched performances by the band, along with appearances by other rock-and-roll artists.

By this time, however, another white singer who was combining rhythm and blues with country and western and gospel music was also on the rise: Elvis Presley (1935–77). Bill Haley continued to have hits into the late 1950s, but he was largely eclipsed by Presley and other emerging rock and rollers. At the same time, Black artists such as Little Richard (b. 1932), Fats Domino (b. 1928), and Chuck Berry (b. 1926), who had been playing R&B all along, began to enjoy popularity as well. By the late 1950s, Bill Haley’s time had passed, though he continued performing through the 1960s and 1970s.

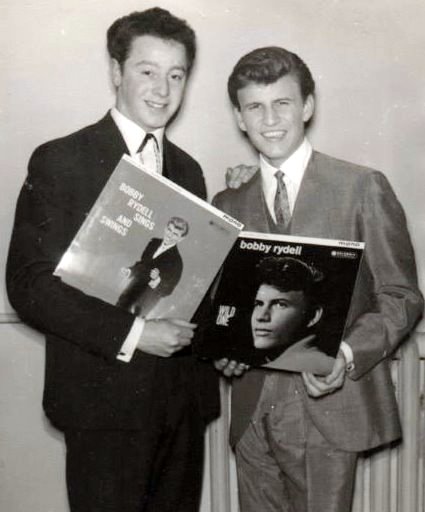

As Haley’s star was fading, Philadelphia’s was on the rise. American Bandstand, the teen music and dance show that began as a Philadelphia radio program in the late 1940s and then was a locally broadcast TV show from 1952 to 1957, went national in 1957. Under the direction of its charismatic host, Dick Clark (1929–2012), Bandstand became America’s most influential outlet for the youth pop music market. Clark had close working relationships with (and in some cases, business interests in) Philadelphia independent record labels and regularly featured their artists on Bandstand, giving these artists’ careers a major boost. Cameo Parkway Records had a long string of hits in the late 1950s and early 1960s, with local artists such as Charlie Gracie (1936-2022), Bobby Rydell (1942-2022), the Dovells, the Orlons, Dee Dee Sharp (b. 1945), and Chubby Checker (b. 1941). Checker’s “The Twist” sparked a long-running dance craze. Chancellor Records, another Philadelphia record company, produced South Philadelphia teen idols Frankie Avalon (b. 1940) and Fabian (b. 1943).

As a result of all this activity, Philadelphia was the epicenter of the rock and roll industry in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Its heyday ended in early 1964, however. Two events—occurring on the same weekend—signaled the beginning of the end of the city’s preeminence. Dick Clark, looking to build his media empire, moved American Bandstand to Los Angeles. The show’s inaugural broadcast from California was Saturday, February 8, 1964. The following night the Beatles made their epochal first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, ushering in the “British Invasion.” English bands largely swept American artists, including many Philadelphia hit makers, off the charts for several years. (Philadelphia’s low profile in popular music was relatively short lived. The city came into prominence again in the 1970s when Philadelphia International Records became the trendsetter with its unique, homegrown style of soul and R&B known worldwide as the “Sound of Philadelphia.”)

The emergence of rock and roll in the mid-1950s had a major impact on American popular culture. Rock historians often point to the pivotal moment on July 5, 1954, when Elvis Presley recorded the blues tune “That’s All Right” at Sun Records recording studio in Memphis. This was certainly a turning point in rock-and-roll history, and Presley’s transformative role in the early development of the music is undeniable. But rock and roll’s first breakout artist was Bill Haley, a Philadelphia-area country-and-western musician who in the early 1950s took his music, and the world, in a new musical direction.

Jack McCarthy is a music historian who regularly writes, lectures, and gives walking tours on Philadelphia music history. A certified archivist, he directs a project for the Historical Society of Pennsylvania focusing on the archival collections of the region’s many small historical repositories. He has served as consulting archivist for the Philadelphia Orchestra and the 2014 radio documentary Going Black: The Legacy of Philly Soul Radio and gave several presentations and helped produce the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s 2016 Philadelphia music series “Memories & Melodies.” (Author information current at time of publication.)

Continue to Rock Music and Culture, 1960s to Present.

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Charlie Gracie to bring rock legacy to Main Street Music (WHYY, February 24, 2012)

- Chubby Checker sings praises of Settlement school's music lessons for low-income kids (WHYY, March 7, 2012)

- Pennsylvania's tallest residential building to rise on South Broad (WHYY, December 17, 2013)

- Chubby Checker's Philly past (WHYY, March 20, 2015)

- Frankie Avalon will lead Philly's Columbus Day Parade (WHYY, October 9, 2015)

Links

- "Rock the Joint," Jimmy Preston and His Prestonians, 1949

- “Rock The Joint,” Chris Powell and the Blue Flames, 1949

- “Crazy Man Crazy,” Bill Haley & His Comets, 1953

- “Rock Around the Clock,” Bill Haley & His Comets, 1954

- Dick Clark on the early history of American Bandstand, 1998 (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- American Bandstand Historical Marker (ExplorePAhistory.com)

- Rock 'n' Roll: Beginnings to Woodstock Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)