Montgomery County, Pennsylvania

Essay

The early Europeans who settled in what would become Montgomery County in the eighteenth century tended prosperous farms, forges, and mills. They depended on the Philadelphia market to sell their products and on its port to connect them to the wider colonial world. Subsequent generations built a dense transportation network that linked county laborers, suppliers, and consumers with each other and with the city, fueling the county’s prosperity across the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Beginning in the 1950s, however, county residents depended less on Philadelphia for employment, entertainment, shopping, and other daily activities. By the close of the twentieth century, Montgomery County had become an economic engine in its own right, boasting the largest population and by far the largest job base among the counties surrounding Philadelphia.

Lenape people, along with some Dutch and Swedes, inhabited this land before William Penn (1644-1718) acquired it in 1681 and sold what he called the Welsh Tract to Quakers fleeing from persecution in Wales. The newcomers gave Welsh names like Gwynedd and Bala Cynwyd to their communities. English Quakers also acquired land in the area that eventually became lower Montgomery County. Many Germans arrived during the eighteenth century, including Schwenkfelders who settled there as a group.

Penn encouraged early settlers to form townships and practice self-government. Among the earliest to incorporate were areas located nearest to the port of Philadelphia. They included Cheltenham Township, incorporated in 1683, Plymouth in 1701, Abington in 1702, Whitemarsh in 1704, and Lower Merion in 1714. Those early incorporations were hardly surprising, since originally those townships were included within Philadelphia County. After the American Revolution people in the upper part of Philadelphia County petitioned the state Assembly for a separate county, complaining about the inconvenience of traveling all the way to Philadelphia to conduct business at the county seat. In 1784, state authorities carved Montgomery County out of the original Philadelphia County and placed the county seat in Norristown.

From the county’s earliest days, farmers participated in long-distance commodity trading through the Philadelphia port. They sent much of their wheat crop to Philadelphia to be milled into flour for export to Europe. Later the railroad system opened broader domestic markets to county farmers, but at the same time brought greater competition from elsewhere. Local farmers eventually reduced their grain crops in the 1880s when cheap Midwestern grain flooded East Coast markets. Montgomery County farmers shifted more heavily toward dairy production, because rail lines could quickly carry perishables to broader markets.

Building a Dense Transportation Network

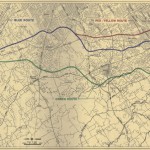

Beginning in the early 1800s, the county embarked on an era of turnpike construction. Companies built hard-surface, all-weather roads to serve forges and mills, and the freight hauling necessary to operate them. They maintained those roads by selling stock and collecting tolls. Across the nineteenth century, turnpike companies built at least two hundred miles of such roads in Montgomery County.

Germantown Pike had served from 1687 as a simple cart road from Philadelphia through Germantown, and northward to Plymouth Meeting. Between 1801 and 1804, investors lengthened and improved it, transforming the road into the Germantown and Perkiomen Turnpike. Eventually investors extended the road as a turnpike all the way to Reading, completing that project in 1815. Another major north-south route originated as a road connecting Philadelphia to Bethlehem during the 1700s; in 1804 it became a toll road, the Bethlehem Turnpike.

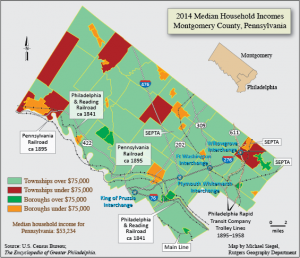

Starting in the 1830s county residents could travel by rail as well. Residents of Lower Merion Township gained easy access to Philadelphia when the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad’s Main Line passenger service crossed through the lower corner of Montgomery County on its way outward to Chester County. Taken over by the Pennsylvania Railroad during the period of rail consolidation, it eventually became one of the busiest commuter rail lines on the East Coast.

The Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown Railroad (PGN) began operating within Philadelphia County in 1832, and by the spring of 1835 it had made its way outward to Norristown. (PGN became part of the Reading Railroad system in 1869.) In 1841, when the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad opened its line along the Schuylkill River to the coal fields in northeastern Pennsylvania, it began hauling anthracite to power factories in Pottstown and Norristown as well as Philadelphia.

Rail Competition Builds

In 1884, the Pennsylvania Railroad built a competing line along the Schuylkill River to haul both freight and passengers. After World War II the fortunes of anthracite coal declined as the nation relied more on oil and natural gas, and both rail lines eventually ceased hauling coal.

Rail lines pushed development northward beyond the well-traveled southern portion of the county. The North Pennsylvania Railroad line (which later became the Lansdale Regional Rail Line) made Cheltenham Township the city’s gateway to the northern suburbs and gained importance as a local carrier of passengers along Bethlehem Pike, with branch lines from Lansdale to Doylestown (1856), from Glenside to Hatboro (1872), and on its Jenkintown-Beth Ayres-Langhorne-Bound Brook line (1874-76).

To attract passengers, rail investors promoted leisure travel. Shortly after the Civil War, the Perkiomen Railway Company started running a passenger line from Valley Forge north along the Perkiomen Creek up to Pennsburg Borough. In the 1920s the Perkiomen Valley became a favored vacation spot served by rail. The Reading Company bought the line in 1944, but the advent of the automobile forced passenger trains on this route to cease operations by 1955.

With leisure travelers in mind, investors in the Pennsylvania Railroad guided real estate development in Humphreysville, a town that straddled the border between Montgomery and Delaware Counties. The railroad company acquired large tracts of land in the area and built a posh hotel for summer visitors, creating by the 1880s a booming summer resort business. To burnish the reputation of the new development, the railroad rebranded Humphreysville in 1871, giving it the Welsh name of Bryn Mawr. With a similar intent to develop Main Line suburbs as affluent enclaves, the railroad company also renamed Athensville in 1873, preferring the Scottish name of Ardmore.

In the 1880s trolley companies began serving passengers for short trips. The first horse car lines ran on DeKalb Street in Norristown in 1884, and Pottstown soon got streetcars as well. Like the railroads, some trolley companies lured new customers by offering leisure travel. Willow Grove Park operated for eighty years as an amusement park from 1896 until 1975. The Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company conceived the park as a way to encourage weekend customers to patronize the trolley lines. One of the biggest attractions was the music pavilion, where John Philip Sousa (1854-1932) and his band played annually from 1901 to 1926, along with other important bands and orchestras.

Another trolley company, the Philadelphia Transportation Company, ran lines from Germantown Avenue to Bethlehem Pike. In 1898 they opened the Chestnut Hill Amusement Park (also known as White City) at the corner of Bethlehem Pike and Paper Mill Road. They intended to provide a park for Philadelphia’s working classes by charging a trolley fare of only a nickel, far less than their competitor’s thirty-cent fare to Willow Grove Park. Nearby residents complained that the new park lowered the tone of the area, however, and by 1912 it closed. A handful of wealthy Chestnut Hill families living near the amusement park had pooled their money, bought the park for about $500,000, and immediately shut it down.

The trolley companies prospered for only a half century. By the 1950s, all these routes had closed and the tracks had disappeared to make way for automobiles.

Mills, Mines, and Manufacturing

Many streams flowed into the Schuylkill River, including the Wissahickon, Plymouth, Sandy Run, Skippack, Pennypack, and Perkiomen Creeks. Early settlers erected dams and built mills to produce grain, lumber, oil, paper and powder. In 1795 the county boasted ninety-six gristmills, sixty-one sawmills, six fulling mills, and ten paper mills. The Langstroth paper mill opened on the Pennypack in Moreland township in 1794. Riverside paper mill in Whitemarsh Township began in 1856 to produce a fine grade of book, card, and envelope paper. Lower Merion Township was especially noted for its mills, including plaster, grist and saw mills.

Water power also enabled early settlers to exploit the area’s rich iron ore deposits. Valley Forge was named for the Mt. Joy iron forge built on Valley Creek in 1742. Those ironworks on Valley Creek devoted a large part of their production to the Revolutionary War effort, which prompted British forces to target that location in September 1777, burning the forge and carrying off supplies. Not long afterward, General George Washington (1732-1799) arrived at Valley Forge in December 1777 to winter his troops there.

Pottstown on the Schuylkill River initially relied on grain mills for local livelihoods. Local mills transported their flour to both Philadelphia and Reading markets. However, by the 1850s the iron and steel industry had surpassed grain mills in economic importance. A bridge-building company founded in 1877 as Cofrode & Saylor was acquired by Bethlehem Steel in 1931, providing thousands of jobs. Pottstown-made iron and steel contributed to major national and international projects like the Panama Canal and Golden Gate Bridge.

Conshohocken, another important industrial town on the Schuylkill River, initially produced spades, saws, iron pipe, and machinery in the 1840s. Alan Wood Iron and Steel Company built the Schuylkill Iron Works there in 1857, and the plant became a mainstay of the borough’s economy. So successful was that enterprise that the company built its own railway in 1907—the Upper Merion and Plymouth Railroad Company—a wholly owned subsidiary operating on both sides of the Schuylkill River. Lee Tire and Rubber Company, founded in 1912, made automobile tires and accessories there until 1980.

The borough of Ambler depended on grain milling to power its early economy, but it suffered losses when the coming of the railroads made it possible for Philadelphia merchants to buy cheap Midwestern grain and grind it themselves. In 1896 Henry Keasbey (1850-1932) and Richard Mattison (1851-1936) built an asbestos plant in Ambler and launched the industry that powered the town for almost a century. They used asbestos mined in Quebec to manufacture asbestos-treated fabric used for wrapping steam pipes as well as asbestos fireproof roof shingles. In the late twentieth century, public health officials publicized the health dangers of asbestos and that industry collapsed, leaving Ambler to once again renew itself.

The dense rail network that emerged in the latter half of the nineteenth century allowed individual towns to specialize in manufacturing and fostered a resilient economy whose diversity of products and services kept the area strong across the economic upturns and reversals of the decades. The variety of products included automobile works in Ardmore, worsted and felt textiles in Bridgeport, shovels and spades in Cheltenham, flags and banners in Collegeville, men’s clothing in Lansdale, and cigars in Schwenksville.

Social Disparities

Even with its diverse and productive economic base, Montgomery County always included residents who did not share in its prosperity. The early European settlers who worked modest-size farms owned some African-descended slaves, though in small numbers. The first U.S. census in 1790 reported a total of 118 enslaved people in the county. By the 1810 census, that number had dropped to three. Many of the county’s Quaker, Mennonite, and Schwenkfelder landowners opposed slavery, and some actively undermined that system.

Starting in the 1830s, thousands of escaping slaves traveled through Montgomery County by the Underground Railroad. Abolitionists would conceal them in homes and barns until the evening hours when they could take night trains on the Norristown Railroad to Philadelphia, where a well-organized network could set them on the path to Canada. One resident in Plymouth Township, George Corson (1803-1860), hid escaping African Americans on his property and also built Abolition Hall as a meeting place for the anti-slavery movement on Butler Pike, near its intersection with Bethlehem Pike. Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) and other famous abolitionists visited there.

Farm workers came mainly from Germany, Britain, and Ireland through an indenture system. Known as “redemptioners,” they bargained with ship captains to give them free passage across the Atlantic; in exchange, the ship captains sold their labor to buyers who came to the Philadelphia docks. The purchaser would buy an immigrant’s labor contract for a specified number of years of service. After working off that contract, the immigrants were free to pursue their livelihoods as independent citizens. Not all succeeded in supporting themselves in farming or trades, sometimes ending up in the county’s poorhouse.

Religion exercised significant influence on daily life, including on education. So strongly did residents prize faith-based education that proponents of universal public education met considerable opposition in Montgomery County. When Pennsylvania passed the Common School Law of 1834, the state allowed residents of local school districts to decide whether to adopt the state requirements and become part of the state system. A majority of local school districts in Montgomery County initially opposed joining the state system, not because they refused to support public education but because they did not want their schools secularized. German Lutherans as well as the Amish, Catholics, Episcopalians, and Quakers preferred faith-based schools. Not until 1853 did the last district in the county join the state system.

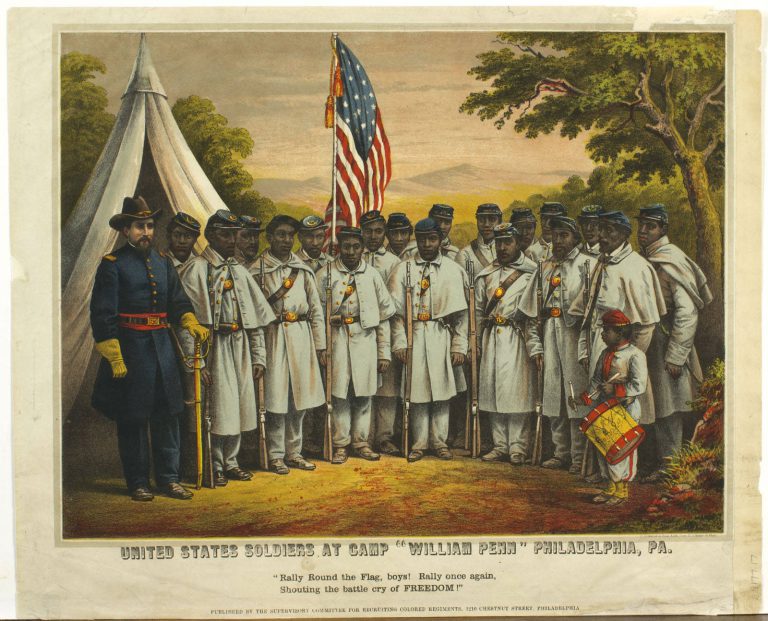

Camp William Penn

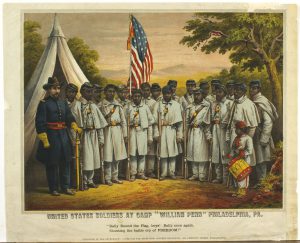

The county’s diversity stemmed not only from differences between towns, but even within towns, one of the best examples being Cheltenham Township immediately across the county border from Philadelphia. One prominent nineteenth-century resident, railroad tycoon and financier Jay Cooke (1821-1905), contributed significantly to that town’s social mix. Cooke had helped finance the Civil War by selling government war bonds. Having been involved in both the abolitionist movement and the Underground Railroad, Cooke along with fellow businessman Edward M. Davis (1811-87) leased land for the U.S. government to operate Camp William Penn, a thirteen-acre training compound for African American soldiers. Frederick Douglass helped recruit volunteers to form so-called “colored regiments,” and in 1865, Harriet Tubman (1822-1913), the legendary Underground Railroad operator, gave a stirring speech to one of the last detachments of soldiers trained there. The camp opened in the summer of 1863, and by the time it closed in 1865 it had trained about eleven thousand soldiers. Cheltenham Township subsequently drew African American residents who regarded it as hospitable.

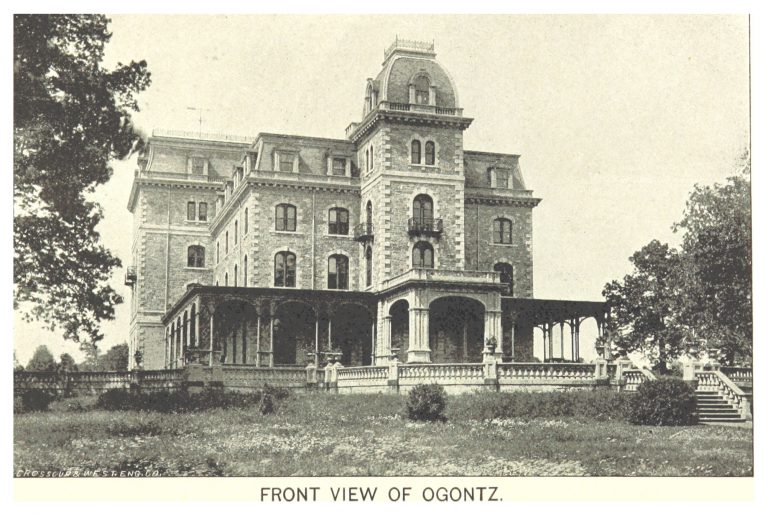

After the Civil War, Jay Cooke and Edward Davis turned to land development that served their own social class. They promoted Cheltenham Township as a place where rich industrialists and merchant families could build mansions befitting their newfound wealth. While Philadelphia families with inherited wealth generally preferred the Main Line or Chestnut Hill, many self-made millionaires built estates in Cheltenham, including a number designed by the noted architect Horace Trumbauer (1868-1938). Subsequent generations often converted Trumbauer’s monumental estates into schools, colleges, seminaries, and other religious institutions.

Even while Gilded Age industrialists chose Cheltenham for their lavish estates, the township gained significant numbers of lower-income Italians who came to work in quarries in the township’s Edgehill section (later known as Glenside). Also in the twentieth century, Koreans established themselves in large enough numbers that Cheltenham became the Korean epicenter of the metropolitan region. Other Asian immigrants arrived, along with many African American residents, so that by the end of the twentieth century Cheltenham was one of the two most diverse municipalities in Montgomery County.

The other markedly diverse municipality was the county seat of Norristown. In the mid-nineteenth century, its mills and factories had drawn large numbers of Irish immigrants, followed by Italians. The Great Migration from the American South to northern cities during and after World War I brought many African American residents to work in Norristown. During the second half of the twentieth century, Latino immigration, especially from Mexico, became the overwhelming source of the increase in Norristown’s foreign-born population. By 2000, Montgomery County had attracted a percentage of foreign-born residents (9 percent) that was smaller than the 11 percent foreign-born in Philadelphia, yet higher than the three other suburban counties in Pennsylvania.

Development Patterns

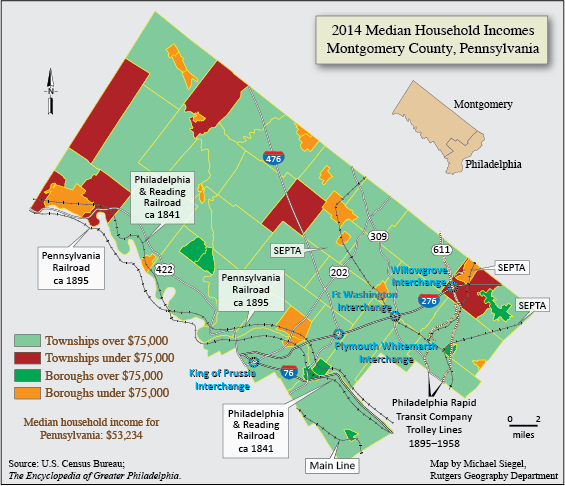

In the 1950s, the construction of the Pennsylvania Turnpike played a significant role in shaping the county’s development. Philadelphia’s business leaders saw the turnpike as an opportunity to link the city to the national highway network, and they vigorously supported construction of the Schuylkill Expressway in 1958 to connect downtown Philadelphia with the turnpike at Valley Forge. What they did not anticipate, however, was the turnpike’s impact in creating a major east-west route across Montgomery County that bypassed Philadelphia entirely, creating new employment and shopping centers along its path and enabling a pattern of daily trips from suburb-to-suburb that eventually surpassed the suburb-to-city travel pattern established during the rail era.

The turnpike exit serving Valley Forge/King of Prussia turned a small village in the 1950s into the most significant job center in Montgomery County. Located at the confluence of the turnpike with Route 202, Route 422, and the Schuylkill Expressway, King of Prussia drew companies in aerospace, defense, and security industries like General Electric and Lockheed Martin, along with many pharmaceutical companies. This prime location also gave rise to the King of Prussia Mall. In 1963 the Kravitz Company began building a strip of anchor stores (Korvette, JC Penney, John Wanamaker, Gimbels) around a supermarket. Starting from that midmarket retail cluster, the mall gradually expanded into one of the nation’s largest shopping centers and shifted toward luxury goods for higher-income shoppers.

To the east of King of Prussia, a pair of turnpike exits created a growth center spanning Plymouth and Whitemarsh Townships. At the Plymouth Meeting exit, an interchange with Germantown Pike provided access to Norristown in 1954, while the second exit opened in 1955 headed north as the Northeast Extension of the turnpike. In 1950, the townships of Plymouth and Whitemarsh had barely begun to suburbanize, but their populations grew dramatically once the turnpike arrived, doubling from 1950 to 1960 and tripling by 1970. The highway interchange also drove business and retail development in the area. The James Rouse Company of Baltimore built a shopping center aimed at middle-income consumers in 1966 at Plymouth Meeting, anchored by Strawbridge & Clothier and Lit Brothers department stores. Plymouth Meeting office complexes attracted many companies, scoring a coup in 1985 when Swedish furniture company IKEA purchased and renovated space for its first U.S. location.

East of Plymouth-Whitemarsh, the turnpike intersected with Route 309 at its interchange in Fort Washington. There a huge business complex, the Fort Washington Office Park, opened on over five hundred acres in 1955. McNeil Pharmaceuticals, a division of Johnson & Johnson, located there, as did Rohm and Haas Chemical Company (which subsequently moved a short distance north on Route 309 to Lower Gwynedd Township).

Willow Grove Naval Air Station

Finally, near the eastern edge of Montgomery County, the Willow Grove turnpike exit at the intersection with Route 611 served the already-existing employment center at Willow Grove Naval Air Station, an airfield built originally in 1926 when Harold Pitcairn (1897-1960) tested airplanes there. The field served as a military base in World War II. (Its advantageous turnpike location later helped the surrounding area to survive the drastic military cuts imposed on the Naval Air Station in the early twenty-first century.) Willow Grove Park Mall opened in 1982 a little more than a mile from the turnpike exit on the former site of the Willow Grove Amusement Park, which had closed in 1975.

The 1980s witnessed the completion of the Route 422 expressway stretching through the county’s quiet west end. Completed in 1985, it connected Pottstown in the north and Collegeville in midcounty with the King of Prussia megaplex. That made the Route 422 corridor attractive to developers. Businesses, most notably pharmaceutical companies, built facilities employing hundreds along Route 422 near Collegeville. Pfizer and Dow Chemical shared a global research and development campus. GlaxoSmithKline located a research and development facility nearby. Wyeth also came to Collegeville. So many pharmaceutical jobs located there that one GlaxoSmithKline vice president referred to the Collegeville area as “the legal drug capital of northeastern America.”

An important path connecting other towns to King of Prussia was Route 202, an east-west route that increased population along its path during the 1980s, when low mortgage interest rates spurred residential construction. Route 202 was a convenient path across the midcounty suburbs carrying local traffic to workplaces, shopping centers, and other destinations inside the county, giving them less incentive to travel into Philadelphia. The boroughs of Lansdale and North Wales became home to multiple facilities owned by Merck Sharp and Dohme, creating a strong employment base in midcounty.

By the opening of twenty-first century, Montgomery County received more daily commuters traveling to its employment hubs than it sent outward. It epitomized the pattern of suburb-to-suburb commuting. It even enjoyed a positive commuting balance with Philadelphia, receiving more daily workers from Philadelphia than it sent into the city. As in earlier eras, the diversity of the county’s modern economic base remained an important strength. The county developed advanced manufacturing specialties like precision instruments, business machines and electronics, along with industrial chemicals and pharmaceuticals. It added high tech jobs in the fields of computer science, information technology, and telecommunications. Service jobs were also abundant in education, health care, retail, financial and professional services.

Coping with Economic Success

The county’s enviable economic growth created winners and losers among its towns. Highways made it convenient to locate production near off-ramps instead of in older population centers. Many companies operating in the county’s older manufacturing centers moved to new facilities. Newer retail developments lured customers away from older shopping districts, causing their deterioration. Over time, the shift of employment and retailing into job centers defined by highway interchanges generated marked differences in taxable resources available to different local jurisdictions.

Not only did older industrial towns lose jobs and employers, they also faced environmental costs left behind when manufacturing plants closed. However, some real estate investors saw opportunities in brownfield sites. After an industrial landmark, Lee Tire Factory, closed in Conshohocken in 1980, developer Brian O’Neill (b. 1960) transformed the vacant factory into an office and light industrial complex called Spring Mill Corporate Center. His brother Michael O’Neill (b. 1963) transformed a 1929 chemical plant, adding an office extension for the Quaker Chemical corporate headquarters. These projects triggered an office and condominium boom in Conshohocken, helped by the town’s advantageous location at the intersection of the Schuylkill Expressway and the Blue Route.

In Ambler, the closing of the former Keasbey and Mattison asbestos company in the 1970s also left behind a major brownfield site. After nearly ten years of environmental remediation and financial problems, the Ambler Boiler House rose from the neglected site as a multi-tenant office building that provided a new workplace within a two-minute walk of a regional rail station. Shortly after that, a nonprofit organization bought the historic downtown Ambler Theater and spent millions restoring its original character. That project anchored additional main street development.

Even the U.S. government left environmental contamination in its wake when it de-commissioned the Willow Grove Naval Air Station, leaving the groundwater in and around the base tainted from years of chemical dumping. When the township of Horsham launched plans in 2015 to develop a multimillion-dollar residential-retail-office complex to replace the military base, its first challenge became environmental remediation.

Planning for the Future

The twentieth century transformed a county that had once boasted a sizable rail network into a suburban landscape shaped largely by highways. Travel from suburb to suburb increased, creating a pattern that was ill-served by rail lines constructed to carry passengers back and forth to Philadelphia. According to the 2015 American Community Survey, 80 percent of Montgomery County workers got to work by driving alone. More than half of all county residents had access to two or more vehicles, and 95 percent had access to at least one vehicle.

Facing this reality of auto dominance in the early twenty-first century, municipalities adopted different development strategies. Some towns sought to take advantage of highway-based transportation patterns. For example, planners in the county seat of Norristown saw their town’s resurgence tied to the very turnpike that had earlier undermined their commercial vitality. For decades, the King of Prussia and Plymouth Meeting malls and suburban industrial parks arrayed along the turnpike had drawn commerce away from Norristown. At the turn of the twenty-first century, Norristown boosters lobbied the state to build a new exit off the turnpike at Norristown in order to spur redevelopment. In 2016 the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission committed to build that interchange, projected for completion by 2020.

Other towns tried to limit auto dependence by creating walkable environments within town centers. Pottstown, for example, worked to reinvent itself as a walkable main street community, restoring its disused train station as a bank and transforming a long-vacant shirt factory into a mixed-use arts center along with affordable housing. By promoting their sidewalks, historic architecture, street trees and storefronts, Pottstown leaders hoped to attract young adults to an urban-style setting.

Despite the successes of some plans adopted by individual municipalities, the county failed to address the broader issue of the massive daily commute caused by so many workers living at significant distance from their workplace, unable to find affordable housing near the job centers where land and housing prices were high. Some communities had adopted zoning laws making it impossible for entry-level workers to find housing near their jobs. In 2006, the Montgomery County Planning Commission began urging municipalities to increase the housing stock accessible to moderate-income workers. However, planners could do little more than urge local officials to promote what they labeled “workforce housing,” since municipalities carried responsibility for land-use and zoning under Pennsylvania law. As a result, housing choices remained limited in many towns and progress towards diversification was slow at best.

The history of Montgomery County more than justified the early settlers’ confidence that they need not depend entirely on Philadelphia markets, wealth, and employers to achieve prosperity. By the opening of the twenty-first century, they had built an economic base and quality-of-life in many communities that ranked among the highest in the metropolitan region.

Carolyn T. Adams is Professor Emeritus of Geography and Urban Studies at Temple University and associate editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Cosby case dominating Montgomery County DA race (WHYY, October 26, 2016)

- Norristown millennials jump into the political fray (WHYY, May 11, 2017)

- Lower Merion remembers desegregation and the end of Ardmore Ave. school (WHYY, September 12, 2013)

- Montco approves plans for 800 miles of bike paths (WHYY, August 14, 2018)

- Montco Republicans square off in primary debate (WHYY, March 8, 2019)