Delaware County, Pennsylvania

Essay

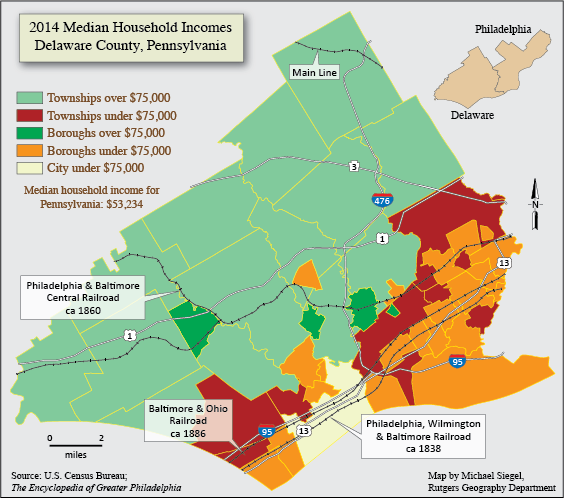

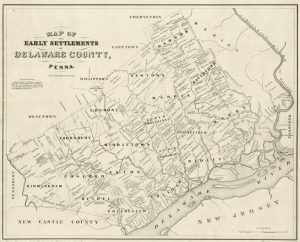

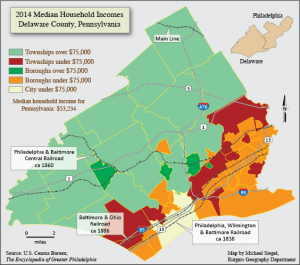

Carved out of Chester County in 1789 (with the remainder of that county lying to its southwest), Delaware County long served as a distinct but close neighbor to the City of Philadelphia. Linked to the Philadelphia port from the eighteenth century onward, the eastern part of the county, including Chester and its neighboring municipalities along the Delaware River, was almost indistinguishable from nearby Philadelphia neighborhoods while much of the rest of the county remained agricultural into the late twentieth century. In the mid-nineteenth century, the introduction of regional railways fostered new town centers at commuter stations. The westernmost section remained predominantly rural until the late twentieth century, when the county began to experience the effects of large-scale development. That mixed settlement pattern created some of the widest social disparities observable in any suburban county in the Philadelphia metropolitan area.

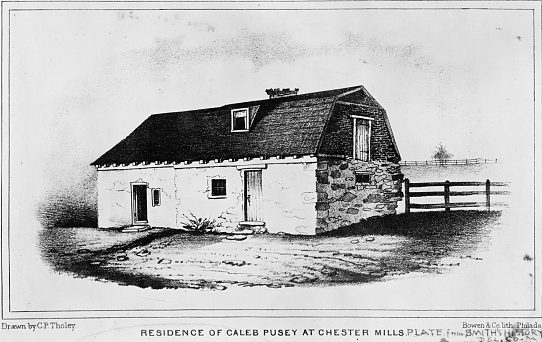

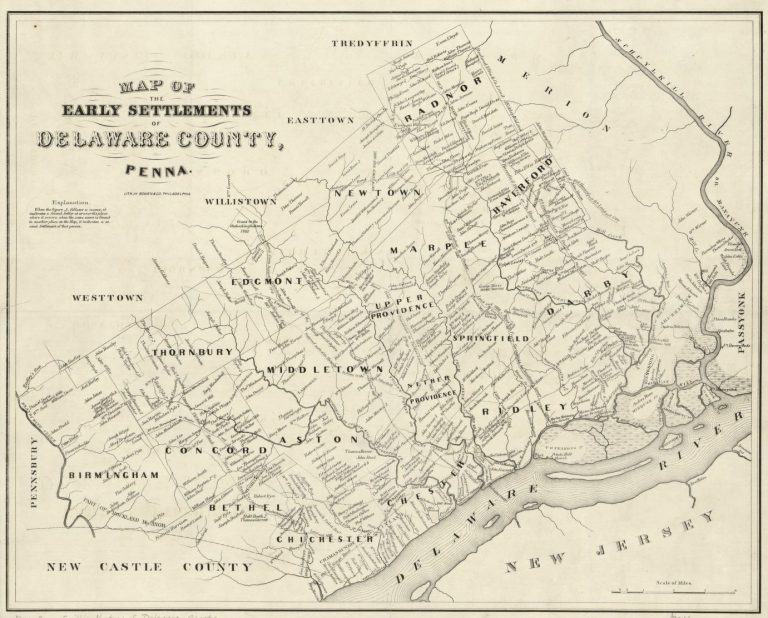

Lenni Lenape were the original inhabitants of the area that became Delaware County. In the early seventeenth century, Swedish farmers settled in the area, while Dutch trappers came to trade pelts. Later in that century, William Penn (1644-1718) gained control of the area as part of a land grant from the English king. Arriving in the new territory in 1682, Penn initially made the existing Swedish settlement of Upland his “shire town,” renaming it Chester after a county in England. Only when an established landowner there refused to sell him enough property for the town to expand did Penn turn north to locate his provincial capital, Philadelphia, twelve miles up the Delaware River.

Although no longer the provincial capital, Chester remained a county seat and continued to serve that role after Delaware County separated from Chester County in 1789. During its early history it remained a small market town, hemmed in by farms and the river. In 1850, when the county courthouse and jail became dilapidated and too costly to fix, residents established a new county seat in mid-county and named it Media. That prompted many prominent county citizens to relocate from Chester to Media, where they built fine brick homes and offices surrounding the new courthouse.

William Penn encouraged the formation of self-governing communities in his new territory. The earliest townships became incorporated well before Delaware County separated from Chester County, some even before 1700. Penn’s followers named their settlements after the places in England that they left behind or adopted Biblical or descriptive names. In Delaware County, these included Darby, Swarthmore, Ridley, and Lansdowne as well as Middletown, Bethel, and Concord. Quakers from Wales settled along the “Welsh tract” on the county’s northern border, where they founded several villages, including Haverford, Radnor, Tredyffrin, and Bryn Mawr, all named for places in Wales.

Some settlers clustered in market towns and manufacturing centers that prospered largely due to their connections to Philadelphia. Living at increasing densities, residents wanted reliable water supplies, well-maintained roads, docks, and other transportation and commercial facilities, and peacekeeping by hired constables. They secured those services by carving out small self-governing boroughs from large townships. Most such population centers sat near the border with Philadelphia, with housing stock and population mix very much like adjacent areas of the city. By the 1880s and 1890s, a number of them had seceded from large eastern townships like Darby, Upper Darby, and Ridley and successfully established themselves as independent boroughs. Over time this historic pattern of intense fragmentation in southeastern Delaware County brought disadvantages to the smallest jurisdictions.

Transportation Routes and Settlement Patterns

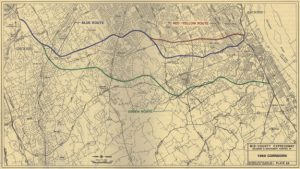

The county’s earliest east-west transportation routes made a lasting impact on development, spawning settlements and boosting their populations over time. One of the most important routes ran along the Delaware River connecting Philadelphia with Wilmington, Delaware. Well before the American Revolution, travelers used a roadway that crossed the southern border of the county between those two cities. In 1851 the state chartered a privately owned company to maintain a section of that roadway as the Darby and Ridley Turnpike (also known as the Chester Pike) and collected tolls to support its upkeep. Eventually, with the creation of the U.S. Highway System in 1926, this route became U.S. Route 13.

Railroads boosted settlements along the Delaware River when, in the first half of the nineteenth century, the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad (PW&B) ran a line along the river. Construction began between Baltimore and Philadelphia in 1837, and by 1850 the extended route connected Delaware County to Washington, D.C., in the south and New York City to the north. In 1870 the PW&B built a line north of the river called the Darby Improvement, aimed at skirting areas prone to flooding and serving growth in this largely undeveloped southeast corner of Delaware County. Around rail stations on that line, developers built new towns such as Ridley Park, Sharon Hill, and Norwood.

The Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad reinforced development along the Delaware River by starting its own service from Philadelphia to Baltimore in 1838 on tracks owned by PW&B. When the Pennsylvania Railroad bought control of PW&B in 1884, the new owner barred its competitor from using its right-of-way. That forced the B&O to build another rail line only a few miles north of the PW&B, completed in only two years. In 1887 the B&O also came into possession of an important north-south rail route when its subsidiary, the Baltimore and Philadelphia Railroad, acquired a rail spur originally built by the Thomas Leiper (1745-1825) family to haul quarried stone from their property on the Crum Creek. The B&O network boosted industrial development by providing direct passenger and freight service to the massive Baldwin Locomotive Works in Eddystone on the Delaware River.

Halfway up the county from the Delaware River, settlers in the early eighteenth century began constructing an east-west route known as the Baltimore Pike, making it among the earliest public roads in the English colonies. Later known as Route 1, this road spurred growth in towns along its path, including Media, Swarthmore, Wallingford, and Lansdowne.

In the northern tier of the county, a major east-west route was created in 1848 when private investors built a toll road called the Philadelphia and West Chester Turnpike. During the 1850s, private enterprisers added a horse-drawn rail line along part of the turnpike, and by the 1890s they had introduced trolley service that ran all the way from West Chester to Upper Darby down the middle of the road that became known as West Chester Pike, later Route 3. These east-west routes of roads and rails made commuting to Philadelphia possible. Developers built communities for the new professional classes to inhabit Victorian-style homes. Almost overnight, builders gobbled up any farmland within walking distance of commuter railroad stations. In 1850, when Media was established, the population of Delaware County was 24,679, according to that year’s census. By 1910 it had grown to 117,000.

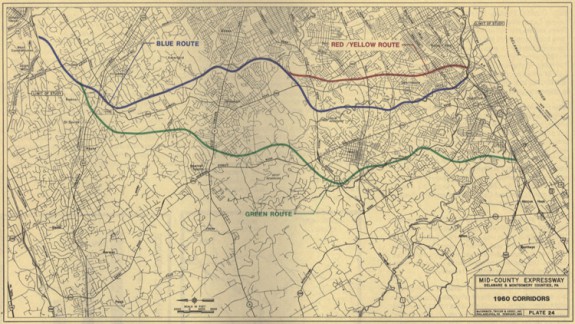

In the late twentieth century, planners added an important new north-south route to the county’s already-dense transportation network. The southernmost section of Interstate 476, known as the “Blue Route” because of its color designation on planning maps, extended through the middle of the county to link the Pennsylvania Turnpike north of Delaware County to Interstate 95 at the county’s southern border. The protracted, thirty-year negotiation over the route, caused mainly by vigorous opposition from residents living in its path, meant that suburban development had already overtaken most of the land adjacent to the highway by the time it opened in 1991. While the Blue Route did not change the settlement patterns much in mid-county, it did increase traffic and commerce at interchanges with the major east-west routes. Some observers credited the Blue Route with spurring redevelopment near the southern end of the highway on the Chester waterfront, including a professional soccer stadium, a Harrah’s casino, and a race track.

Manufacturing and Commercial Centers

Although farming dominated Delaware County throughout the eighteenth century, many paper, cotton, woolen, lumber, and grain mills proliferated along four creeks: Darby, Crum, Ridley, and Chester. Along the Delaware River, early investments in shipping, shipbuilding, brickworks, and iron foundries prompted further industrial development after the Civil War, especially shipbuilding in and around Chester. John Roach & Co., founded in 1864, ranked as the largest shipbuilding company in the United States during the 1870s. By 1900, a third of the county’s population lived in Chester, and the waterfront industrial complex contributed significantly to the country’s defense during both world wars, particularly Sun Shipbuilding Company, founded in 1916 by Joseph N. Pew (1886-1963).

The Baldwin Locomotive Works moved from Philadelphia to the borough of Eddystone on the Delaware River in 1906, and by 1916 it was building army tanks for use on the battlefields of Europe during World War I. Sun Oil Co., also owned by the Pew Family, built an oil refinery in 1901 in Marcus Hook at the southern tip of the county. There the convergence of rail, roads, a deep-water port, and the nation’s growing thirst for petroleum gave rise to the refineries that became the borough’s dominant industry. Other manufacturers located on the Delaware River included Scott Industries, which produced paper and foam products, and American Viscose Co., which made rayon and other synthetic fibers. Ford Motor Co., Boeing Helicopter, and Westinghouse Electric also flourished along the river, drawing workers from all over the country.

From the 1950s onward, Delaware County manufacturers fell victim to the same forces that had already begun to dismantle Philadelphia’s industrial base. From 1970 to 2000, Delaware County lost 54 percent of its manufacturing jobs. Of the manufacturing employment that remained, over a third (38 percent) was in aerospace manufacturing, largely due to Boeing’s continuing presence.

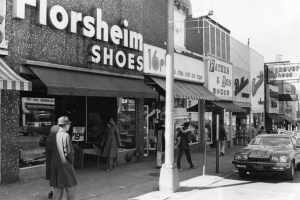

Unlike manufacturing jobs, the service jobs that replaced them were scattered more broadly throughout the county. Retailers, restaurants, and services followed the spread of population into communities that offered desirable housing styles and schools. Health care provided another important source of employment, dominated by general medical and surgical hospitals, but also including physicians, residential facilities treating intellectual disabilities, community care for the elderly, and nursing homes.

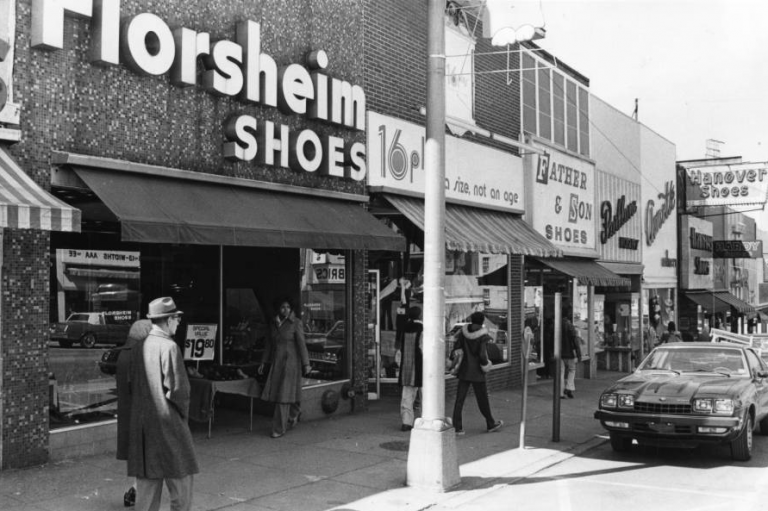

In some cases, shopping malls served as focal points for development. For example, the Springfield Mall, a 590,000-square-foot, two-level facility opened in 1974 along Baltimore Pike, near its busy intersection with Pennsylvania Route 320. Its original anchors included a John Wanamaker department store. Although the mall declined during the 1980s, it recovered strongly after the Blue Route opened in 1991, helping to spawn a nearby development of age-restricted townhomes, condominiums, and golf course, as well as the Springfield Health Plex and hospital. Shopping centers and retirement communities like these brought increased traffic and commerce to the county’s major east-west corridors like U.S. Route 1 and West Chester Pike.

Population Growth and Change

Beginning as early as the 1830s and continuing through World War II, early industrial opportunities along the Delaware River drew thousands of Irish Catholic workmen to mill and factory jobs in Upper Darby and Clifton Heights across the border from West Philadelphia. Polish and Italian workers came in the twentieth century to work in factories or to run small businesses. Irish, Polish, and Italian immigrants built churches and parochial schools that flourished until the 2000s, when they started to decline along with the county’s aging Catholic population.

Some companies built housing for their workers. The Washington Print Works built Eddystone Village, named for a lighthouse in England. The village, just north of Chester, subsequently became the Borough of Eddystone. Flooring manufacturer Congoleum Nairn Inc. built housing for its workers in Trainer on the Delaware River west of Chester City. In other instances, independent developers built housing for workers in the county’s older settlements, ranging from apartment buildings to row houses to small cottages, in Chester, Clifton Heights, Eddystone, Ridley, and Nether Providence before and during both world wars.

When manufacturing declined, housing values in many blue collar neighborhoods also declined. As these neighborhoods became more affordable, they drew growing numbers of minority and immigrant residents, especially in the last few decades of the twentieth century. By the 1990s, African Americans comprised 80 percent of the population of the city of Chester and some of the inner suburbs along the border with Philadelphia, such as Yeadon, Colwyn, and Darby Borough. Because of its transportation system and large rental housing stock, Upper Darby—the county’s largest municipality in both area and population—became a major catchment area for immigrants from Eastern Europe, Asia, and Latin America. Asians from the Indian subcontinent constituted the majority in tiny Millbourne, the county’s smallest municipality at just .07 of a square mile, nestled between Philadelphia and Upper Darby Township.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, many municipalities remained more than 90 percent white. They included townships in the northern and western suburbs like Newtown Square, Edgmont, Chadds Ford, and Bethel. Perhaps more surprisingly, some boroughs in southeastern Delaware County with homes priced affordably for a broad range of both white and nonwhite buyers remained over 90 percent white in 2000 (for example, Eddystone, Norwood, Prospect Park, and Ridley Park). The result was a pattern of racial and ethnic separation into predominantly white or Black towns, through a combination of zoning ordinances and informal real estate practices that materialized despite objections from fair housing activists as early as the 1970s.

Social Disparities Amid Changing Political Landscape

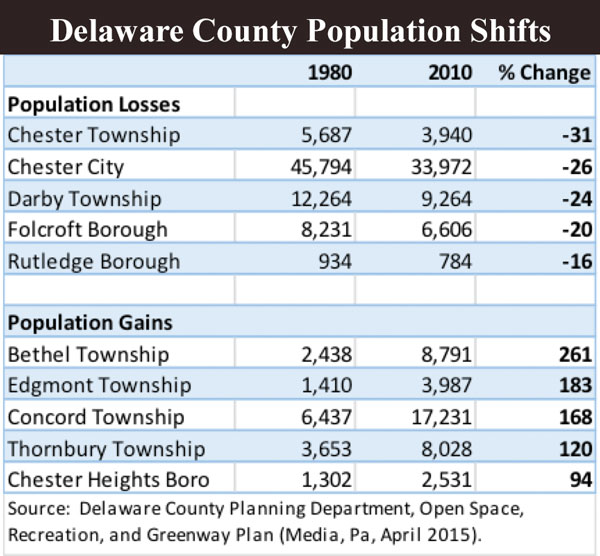

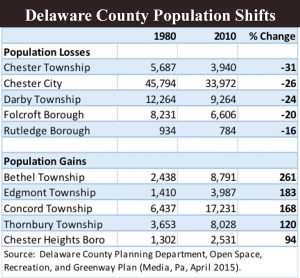

The final decades of the twentieth century witnessed dramatic population shifts in Delaware County, with some older communities losing population while newer suburbs to the west and north gained. Those population shifts mirrored the widening income gaps between communities. By 2014, fast-growing Bethel Township boasted a median household income of $123,349, while the shrinking number of residents in Chester City survived on a median household income of only $28,607.

These contrasting development patterns created differences in tax resources and therefore in municipal services. Compared to area townships, boroughs were especially disadvantaged because their very small landmasses (in some cases only one square mile or less) were entirely developed, leaving little room to create new taxable property. Their municipal budgets were too small to fund first-rate services. With stagnating tax bases, school districts collected fewer dollars to spend on public education. Among the fifteen school districts in Delaware County in 2015, the three highest-spending districts spent over $22,000 on each student; these were the districts of Radnor Township, Rose Tree Media, and Marple-Newtown, all serving children in the northern suburbs and mid-county. The four lowest-spending districts (William Penn, Penn-Delco, Southeast Delco, and Upper Darby) spent less than $16,000 per student. Three of those four low-spending districts hugged the western boundary of the city of Philadelphia.

To make such stark inequalities worse, the lower-spending districts were educating higher shares of low-income children. For example, in 2015 only 9 percent of the school population in high-spending Radnor Township had incomes low enough to qualify for free- and reduced-prices lunches. That same year, low-spending districts like Southeast Delco and William Penn served student bodies in which 82 percent and 70 percent, respectively, qualified for the lunch program. Both these districts served multiple towns too small to operate their own schools and densely developed so that they had little prospect of adding new property to bolster their tax base. Southeast Delco educated children from three boroughs plus one township, while the William Penn School District served six small boroughs crowded together at the Philadelphia border. Despite levying relatively high property tax rates compared to their neighbors, these older communities remained consistently underfunded.

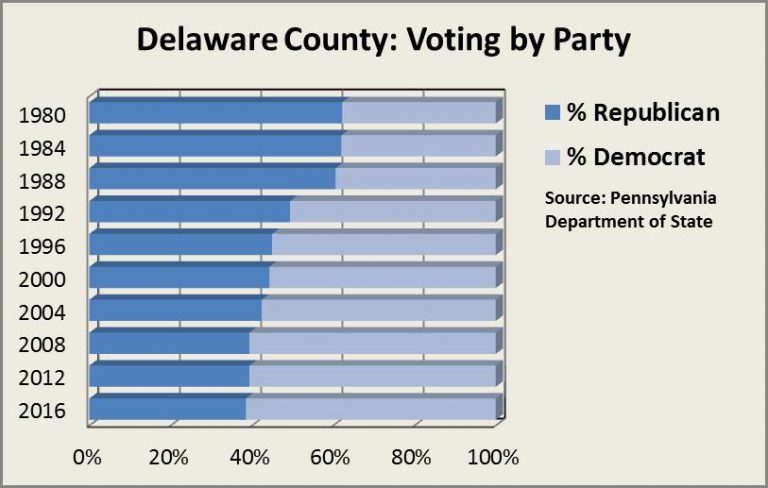

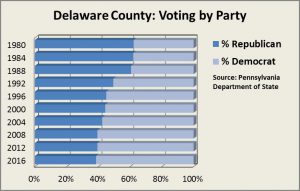

According to the 2010 census, the county population was roughly 80 percent white and 18 percent Black, with Asians and Hispanics making up the rest. The growing proportion of minority residents appeared to have an impact on political attitudes and behavior. Historically the Republican Party dominated county politics starting before the Civil War and continuing through most of the twentieth century. Republican-dominated municipal governments were able to keep many communities virtually all white for decades but, as in Upper Darby and Millbourne, the racial makeup of some communities started to change at the end of the twentieth century. The political makeup of some municipal governments such as Media and Swarthmore also slowly changed, while gerrymandering of state and congressional election districts helped the Republican Party maintain its grip on the county as a whole. In national elections, the voters shifted in 1990s toward Democratic candidates. County voters who had given majorities to Republicans Ronald Reagan (1911-91) and George H.W. Bush (1924-2018) favored Bill Clinton (b. 1946) in the 1990s and continued supporting Democratic presidential candidates in subsequent elections.

Twenty-First Century Development Patterns

While the populations of many communities in eastern Delaware County remained stable or declined over time, at the end of the twentieth century the western suburbs experienced growth and sprawl. The county’s last valuable unprotected wetlands, woodlands, and farms were located in the western and northern municipalities where new development rapidly replaced open land. As the population in that area continued to grow, so did the need for open space. To preserve farms and woodlands, the county government published a plan in 2013 for economic development and land use that encouraged infill development to preserve and rehabilitate existing infrastructure and housing stock wherever possible while also protecting green spaces.

Key to that strategy was revitalizing the Delaware riverfront. Nearly twenty-five million people lived within a two-hour drive from the heart of Delaware County’s waterfront industrial area, making that location potentially attractive to businesses that relied on quick access to markets up and down the East Coast. Moreover, the nearby Philadelphia International Airport provided passenger and cargo service to waterfront producers.

County planners favored guiding residential investments on the eastern side of the county into transit-oriented developments around regional rail lines and bus ways, for example, at Sixty-Ninth Street (Upper Darby/Millbourne), in Darby, Lansdowne, Media, Parkside, Ridley Park, and Swarthmore. For the western and northern suburbs, planners advised a shift in development patterns away from the sprawling single family homes popular in the 1990s and 2000s, to more dense housing patterns such as townhomes.

No matter how carefully the county government documented the need for and potential benefits of such development strategies, the structure of local government in Pennsylvania gave primary responsibility for regulating land-use to local governments, which controlled zoning. County governments played only a limited role, mainly advising and supporting local planning efforts. Not surprisingly, affluent townships like Radnor and Middletown devoted the most open space for both recreational and passive uses. Local governments in those communities, along with other affluent townships like Concord, Nether Providence, and Upper Providence persuaded citizens to approve bond issues for millions of dollars to purchase and preserve open space. In contrast, leaders in the older suburbs, especially the small boroughs, faced greater obstacles. These small, densely-populated communities possessed few undeveloped parcels. Moreover, local leaders felt pressed to develop any available spaces in order to bolster their precarious tax bases.

One large-scale example of the trend to direct new investment into already-developed locations involved repurposing Granite Run Mall in Middletown Township, near the center of the county. That mall, opened in 1974 as a middle-class shopping venue, failed to compete against e-commerce and the retailers occupying Springfield Mall. By summer 2015, an investment partnership that included longtime developer Bruce Toll (b. 1943) demolished the retail spaces located between two large anchor stores, in order to replace them with high-end retailers and restaurants. The plan would transform the site into a mixed-use town center called “The Promenade at Granite Run.” This new incarnation included not only retail but also hundreds of residential apartments, a renovated movie theater, bowling alley, and seven thousand square feet of pediatric offices operated by Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Delaware County’s long arc of development created dramatic contrasts: from a gritty industrial belt along the Delaware River, to Victorian towns built around rail stations, to pastoral landscapes painted by Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009) in Chadds Ford on the county’s western edge. These stark differences created both challenges and opportunities for county leaders. The broad variation in the age, character, and social composition of different communities, while making coordinated planning difficult, also insured that Delaware County offered living choices for newcomers of almost all backgrounds and means. The combination of abundant rail transportation, high-density town centers, and surviving open spaces made the county a prime candidate to adopt a “smart growth” plan aimed at concentrating future development in existing settlements in order to preserve natural landscapes.

Jodine Mayberry is a retired journalist. She was a legal writer and editor for West Publications, a division of Thomson Reuters, for 18 years. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Carolyn T. Adams is Professor Emeritus of Geography and Urban Studies at Temple University and associate editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Sudden Sunoco closing rattles Delco workers, residents (WHYY, December 2, 2011)

- Casey stumps for defense jobs in Delco (WHYY, December 12, 2011)

- ConocoPhillips employees leave Delco plant after first round of layoffs (WHYY, January 26, 2012)

- $5 million grant to help Delco refinery workers find new jobs (WHYY, March 27, 2012)

- Boeing announces layoffs at Delco plant (WHYY, June 10, 2013)

- Dems pushing for further gains in Delaware County (WHYY, September 3, 2013)

- Granite Run Mall destined for reconstruction as open-air 'town center' (WHYY, March 10, 2015)

- As Delco judge ponders Chester Upland schools' fate, parents left in the lurch (WHYY, August 24, 2015)

- Two Delaware County Catholic parishes to weigh a merger (WHYY, February 8, 2016)

- DelCo officials rail against bill to put gambling in restaurants, bars to fund Pa.'s coffers (WHYY, June 8, 2016)

- DelCo township actually decreases property taxes (WHYY, December 14, 2016)