Philadelphia and Its People in Maps:

The 1790s

By Paul Sivitz and Billy G. Smith

Essay

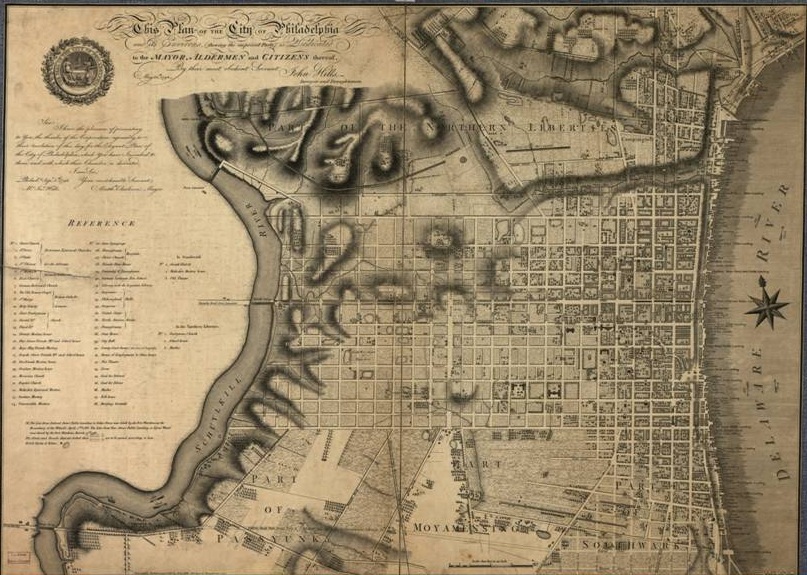

Philadelphia was the premier urban city in North America during the Early National era, a city so admired that people nicknamed it the “Athens of America.” Between 1790 and 1800, it was the official political capital of the United States. It served as a major commercial hub of the nascent nation and became its financial center during the 1790s. Philadelphia was the focal point of intellectual and high culture in the new country as well. As the largest metropolitan area in America, it had a significant impact on region, acting as a magnet for people, wagons, goods, money, and produce from New Jersey and southeast Pennsylvania and sending out its products and setting up commercial and other connections in the region in turn.

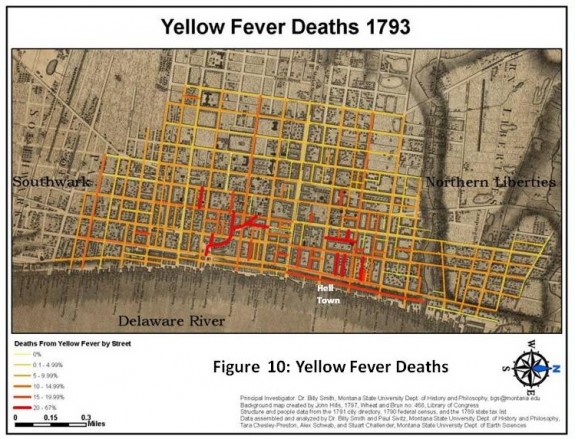

The capital of the United States officially moved on December 6, 1790, from New York City to Philadelphia, where it remained for the next decade before moving again to the District of Columbia. The Pennsylvania city was a fitting capital. Not only was it geographically located near the midpoint of the new nation, but it also had served as the unofficial political center for the past fifteen years. The Second Continental Congress signed the Declaration of Independence in the city in 1776, and the United States Constitutional Convention met there in 1787. Philadelphia also served as the residence of Congress during most of the Confederation Era (1776-1787). While many Philadelphians wanted to keep the capital in their city after 1800, political compromises over the national debt and related issues and the desire of southerners to move the capital to an area bounded by slave states, among several concerns, led Congress to move the capital southward. A series of deadly yellow fever epidemics plaguing Philadelphia in the 1790s also persuaded politicians to move.

The first federal census takers in 1790 counted 44,096 residents in the city of Philadelphia and its adjacent suburbs of Southwark and the Northern Liberties, making it the most populous urban center in the new nation. A decade later, the federal census recorded 67,811 people in Philadelphia. The city thus grew at an exceptionally rapid rate of more than 4 percent annually during the 1790s, despite very high death rates, especially during the yellow fever epidemics responsible for at least 9,000 deaths. High birth rates accounted for some of the growth. In addition, more than 23,000 passengers landed in the port during the 1790s, while approximately 17,500 others landed in nearby Wilmington, Delaware. Most came from Ireland and the area that is now Germany. Migrants escaping revolutions in France and in St. Domingue (now Haiti) likewise arrived in significant numbers. People from rural New Jersey and southeastern Pennsylvania also frequently moved to the city or its outskirts in search of work. Widows and unmarried women likely constituted a disproportionate number of the migration from the nearby countryside, where they found little employment.

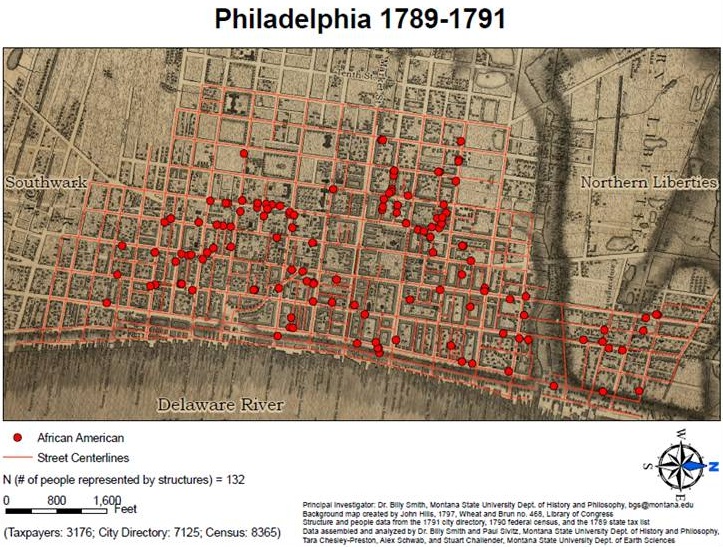

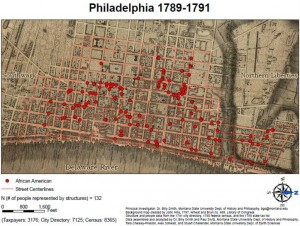

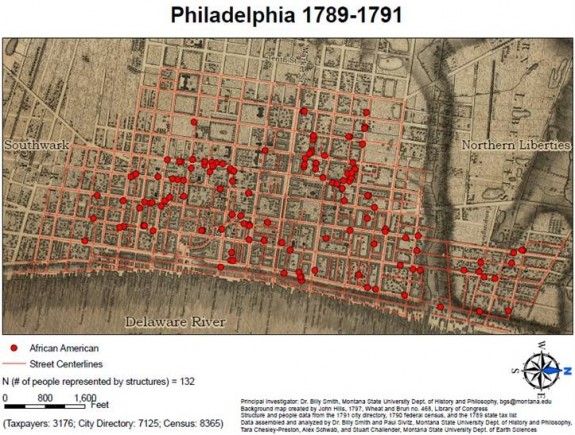

African Americans Drawn to City

Philadelphia served as a special draw for African Americans from the nearby region as well as the southern states. Their numbers tripled between 1790 and 1800, growing from 2,150 (about 5 percent of the city’s population) to 6,436 (approximately 9 percent.) Most black migrants had freed themselves, either legally or illegally. Some earned their liberty by serving in the Continental army or navy during the American Revolution. Others, like Richard Allen (1760-1831) and Absalom Jones (1746-1818), purchased their freedom from their masters. Still others simply ran away from their masters, fleeing bondage and firmly declaring their own liberty. They often found refuge and assistance among the growing number of black Philadelphians. People like Allen and Jones helped build one of the first and most vibrant free black communities in the new nation.

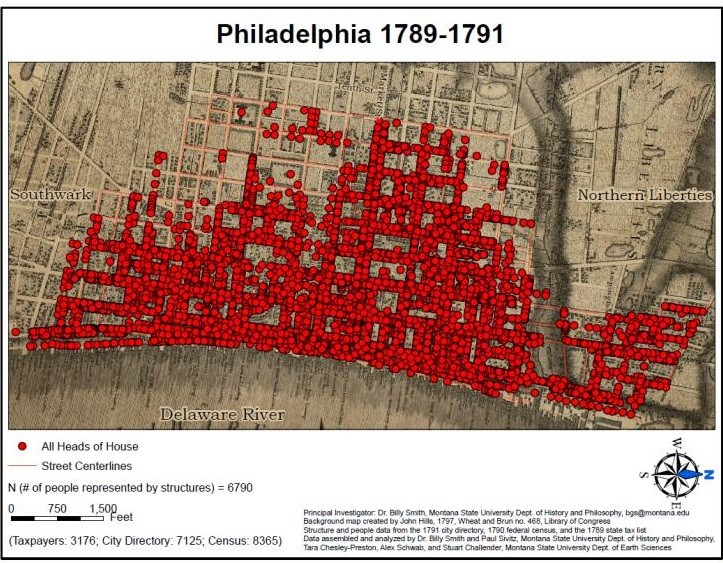

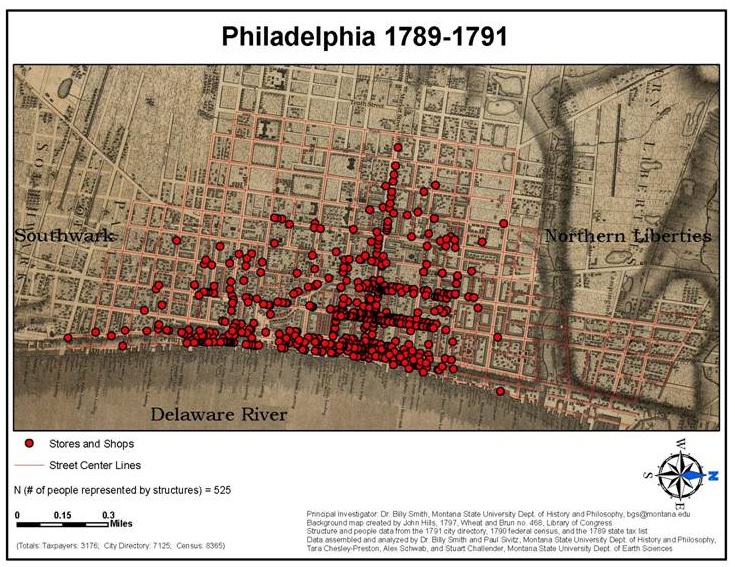

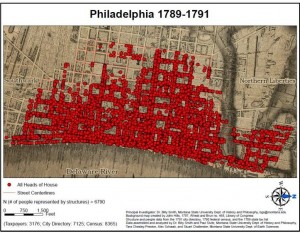

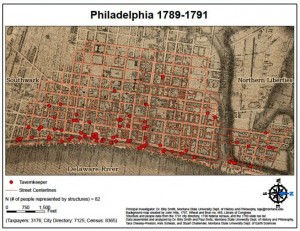

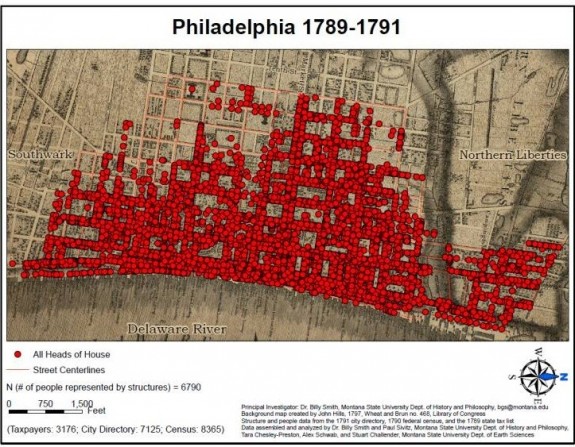

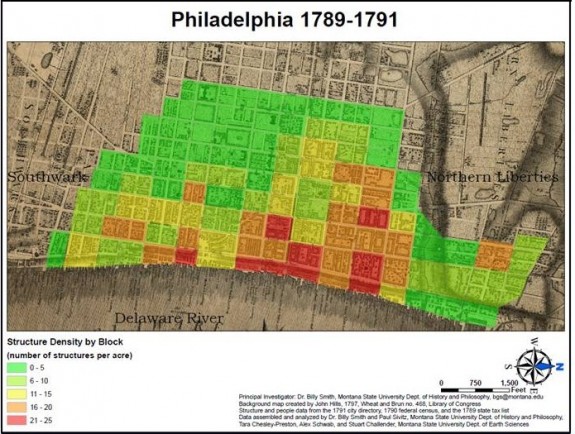

The maps and text below employ relatively new geographic methods to help interpret the past. They use the technology of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to locate every householder in Philadelphia recorded in the census of 1790 or the City Directory of 1791. In the maps, each dot represents a head of household. By visualizing how people organized themselves, we can learn a great deal about the everyday lives of the people of Philadelphia.

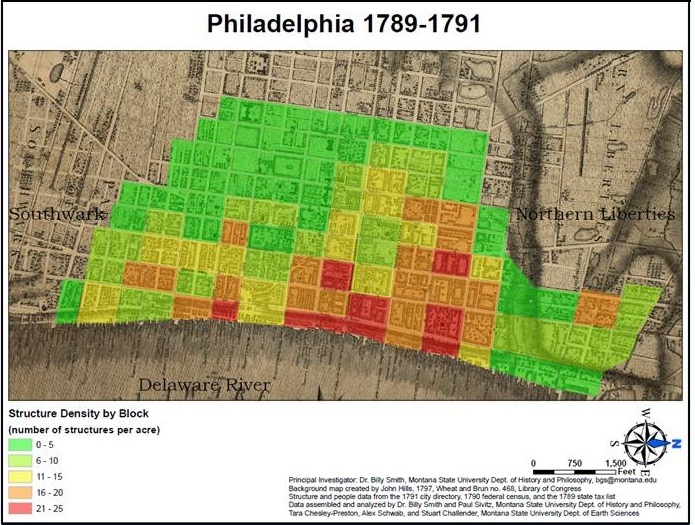

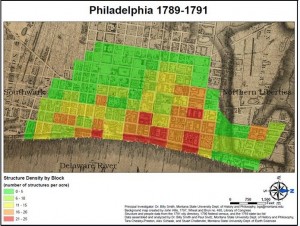

Population Density. For a small city (by modern standards), Philadelphia was surprisingly densely settled during the 1790s. Rather than spread westward from the Delaware River to the Schuylkill River, as William Penn had hoped, Philadelphians subdivided the large blocks with numerous alleys, lanes, and courts and crowded up and down the Delaware River. Since most residents traveled on foot (only wealthy ones rode horses or carriages), they could not move very far away from their workplace or from the markets and stores where they purchased food.

Density of Structures and People. By 1800, the population density measured well over 50,000 residents per square mile, reaching levels of nearly 93,000 near the wharves and just south of the center city. Those figures far exceed density in American cities today; they even approximate some of the worst crowding in immigrant areas of New York later in the nineteenth century. In the map above, the blocks in darker red contained the greatest concentration of people and houses while yellow indicates the least crowded areas.

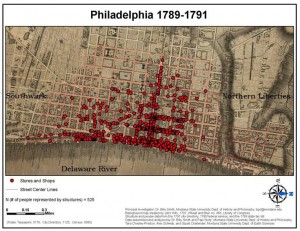

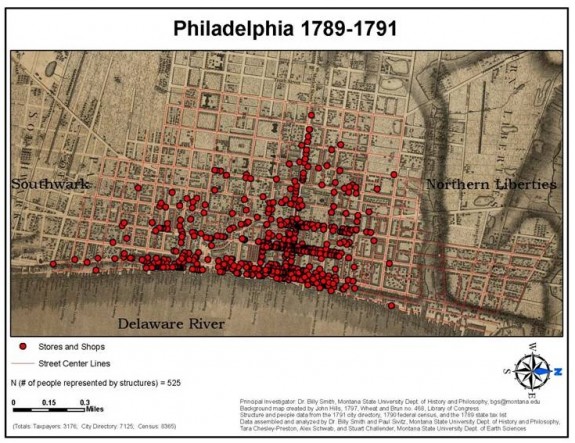

The Elite Corridor of Market Street. Merchants congregated near the sites where they engaged in business, especially along the wharves of the Delaware River. Hundreds of ships docked at the piers each year, unloading imported goods from Europe and sugar from the West Indies and loading wheat and flour onboard. Merchants also gathered near the “elite corridor” (in the phrase of geographers) of Market Street. Shops selling luxury items predominated, including artisans like coachmakers, saddlemakers, goldsmiths, and clockmakers, as well as stores selling imported fashionable goods. Ironmongers—the equivalent of hardware stores—could afford the high real estate of center city, selling all kinds of metal supplies for artisans, housing constructors, and ship builders.

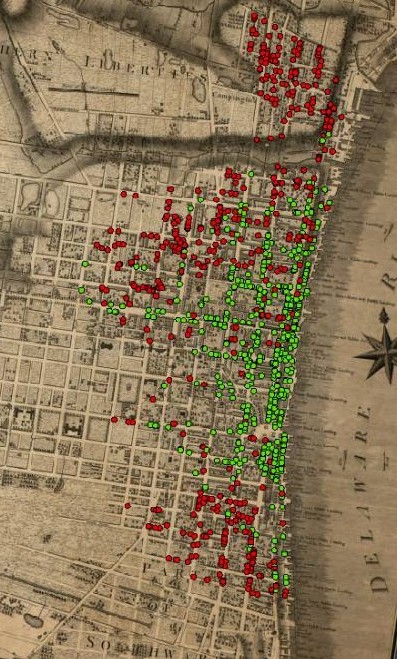

Residential Patterns by Class. A person’s position in the socioeconomic structure often determined the parts of the city in which they could afford to live. Merchants, a wealthier group of citizens represented by the green dots in the map at right, established their business along the wharves of the Delaware River as well as along Market Street. Laborers, the largest occupational group in the city, and comprised of men near the bottom of the class structure, are represented by red dots. Renting inexpensive quarters, married laborers often lived with their families (five people on average) on only a single floor of a three-story structure. Unmarried workers shared rooms in boarding houses. Laborers congregated in the northern, southern, and western areas.

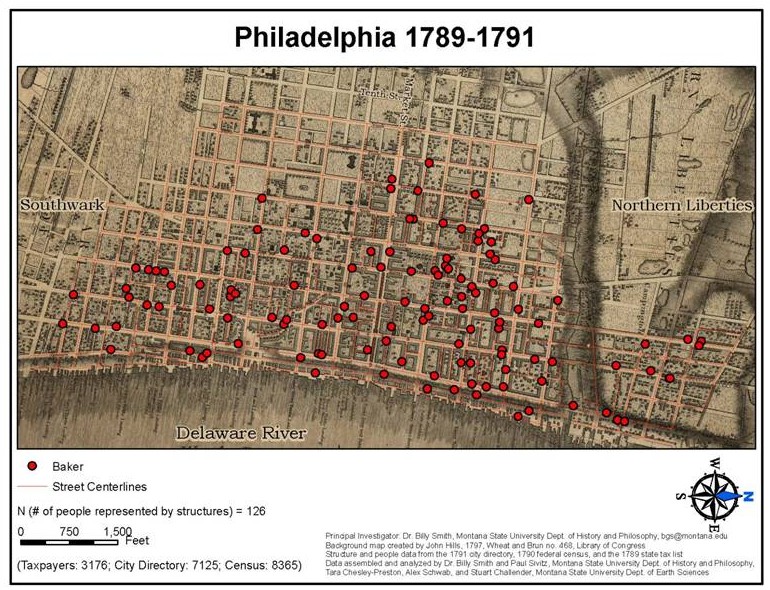

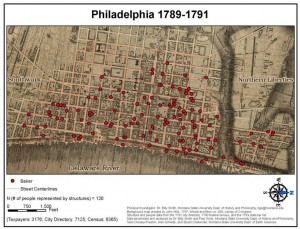

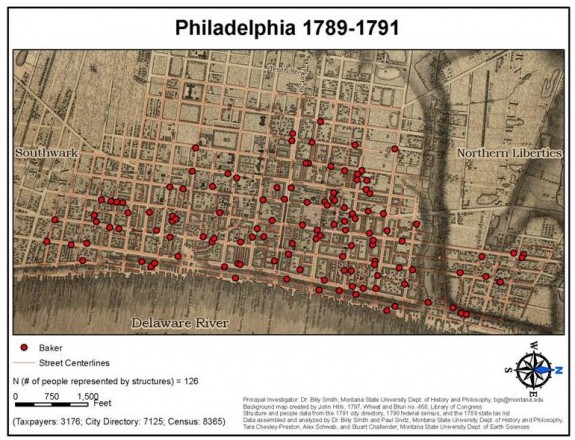

Bakers. Bakers provided inhabitants most with the staff of life. Since most Philadelphians bought bread every day, bakers spread throughout the city for the convenience of consumers. Women in poorer households made the dough and then paid the baker a small fee to bake it. Philadelphians bought most of their fresh foods in the three open-air markets, the most prominent one being in the eastern blocks of Market Street. Serving the southern part of the city, the “New Market” (or Headhouse) stood in Second Street. It has been restored and is designated a National Historic Landmark.

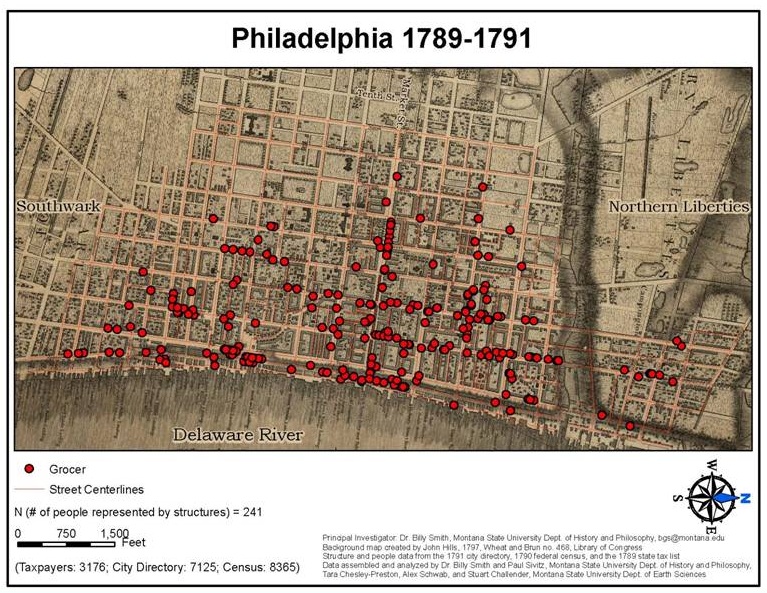

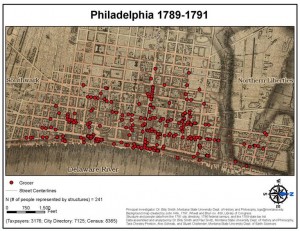

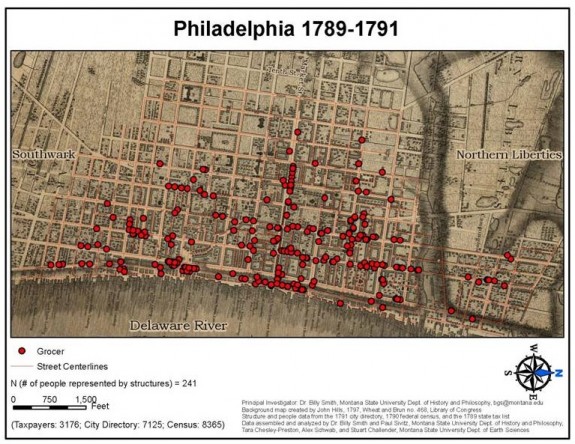

Grocers. Like bakers, grocers appeared throughout the city, although they were less prevalent in the northern and southern suburbs, where poorer people gathered. Accounting for 4 percent of the occupations of householders in the city, grocers sold dried goods, like tea, coffee, and sugar.

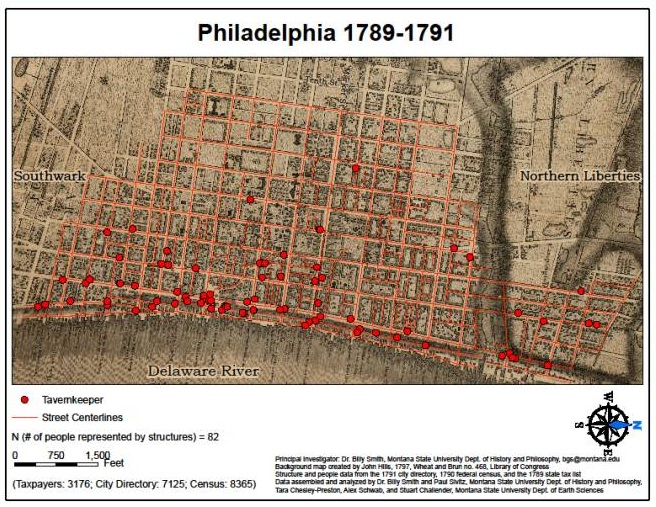

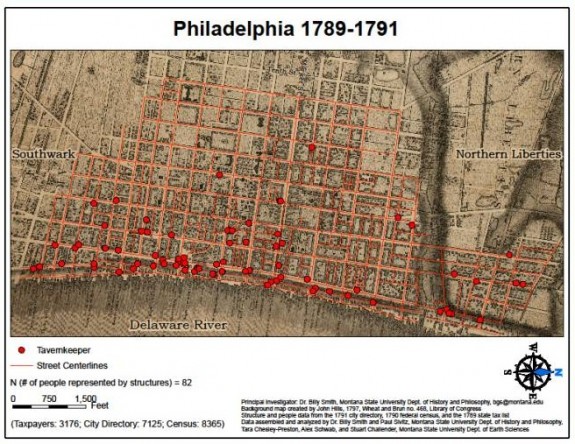

Tavernkeepers. Like most Americans at the time, Philadelphians were a hard-drinking group of people during the 1790s. About 180 tavernkeepers, innkeepers, and beerhouses served the population. Rum produced locally from the molasses imported from the West Indies was a popular drink, as was beer. Many of those establishments settled along the waterfront, where mariners, stevedores, shoemakers, porters, and laborers joined merchants and attorneys in conversation and drinking.

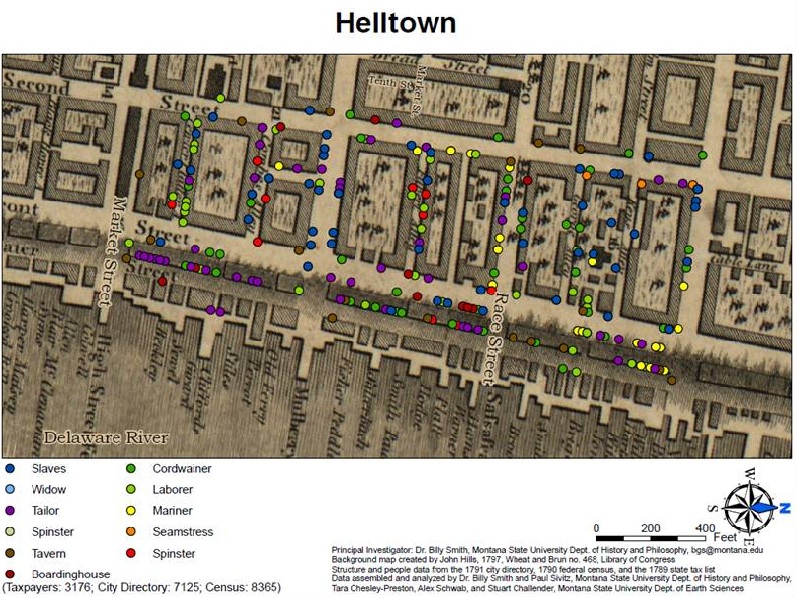

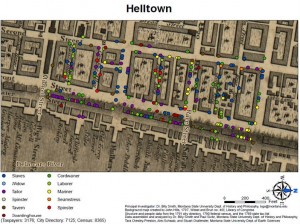

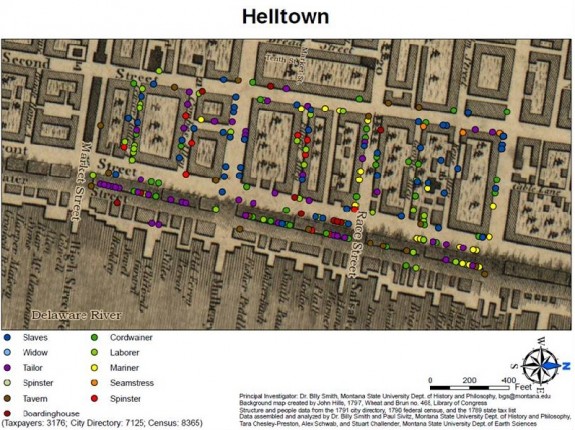

“Hell Town.” The three blocks along the waterfront north of Market Street was called “Hell Town” because it was such a rough neighborhood. It was home to many down-and-out Philadelphians: vagrants, criminals, prostitutes, itinerants, fugitive slaves and servants, the insane, incapacitated, and homeless. These men, women, and children accounted for one out of every ten people in the city, and they often appeared on the dockets of the almshouse, workhouse, prison, and hospital. Also located in this area was the Three Jolly Irishmen, one of the most notorious taverns in the city.

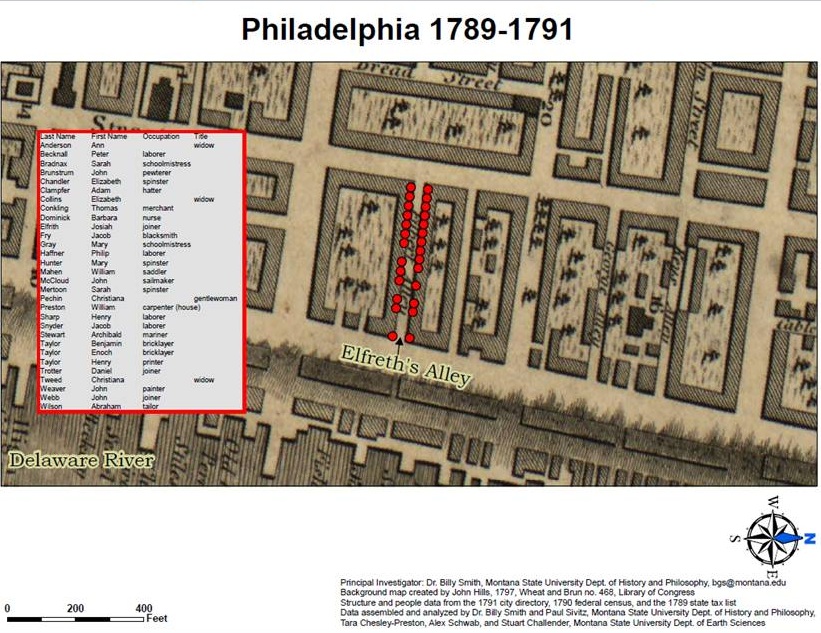

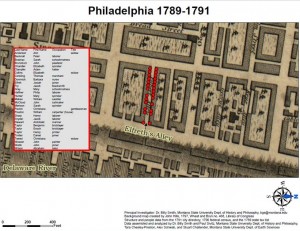

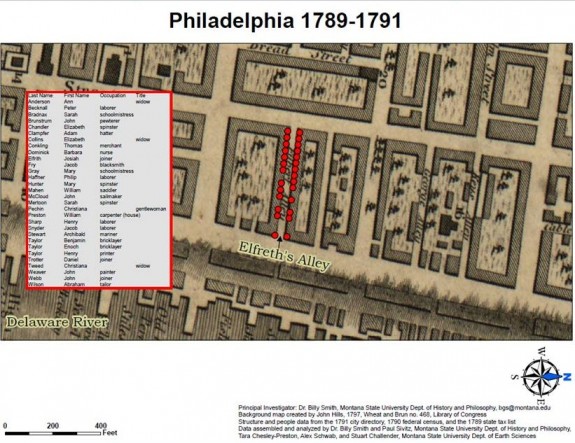

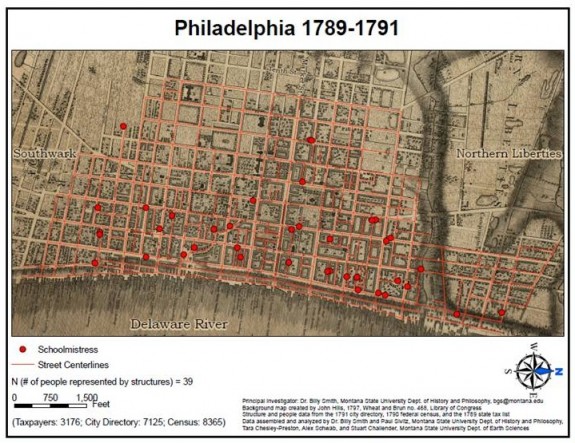

Elfreth’s Alley. Dating from the early eighteenth century, Elfreth’s Alley is perhaps the oldest continually inhabited alley in the nation. In 1790, thirty households with 123 people crowded into the alley. Most of them belonged to the lower classes: laborers, mariners, schoolmistresses, joiners, tailors, and bricklayers. In 1960, Elfreth’s Alley was designated a National Historic Landmark.

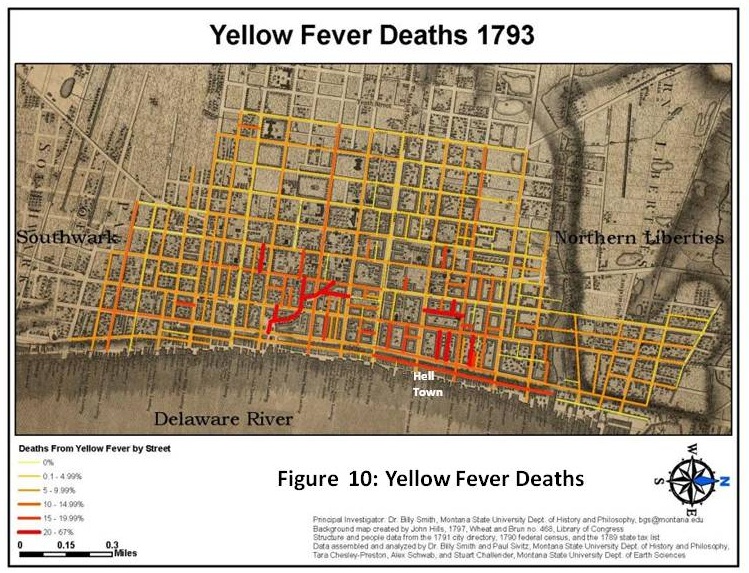

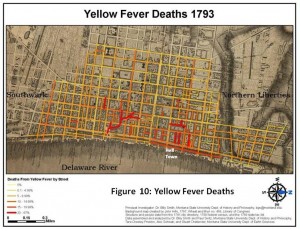

Yellow Fever broke out in epidemic proportion in 1793, 1797, 1798, and 1799. The most severe, and one of the most deadly in American history, occurred in 1793, when an estimated 5,000 inhabitants died. This map records the intensity of the fever, with darker colored lines marking the streets with highest mortality. Yellow fever was most deadly near the northern wharves, where poorer people lived, and where Hell Town was located. It also took a heavy toll along Dock Creek. Both areas furnished breeding places for the Aedes aegypti, the type of mosquitoes that transmit the disease. Wealthier people fled the city while the less affluent stayed behind. As a result, the affliction was class specific, killing the middle and lower classes more often than the elite.

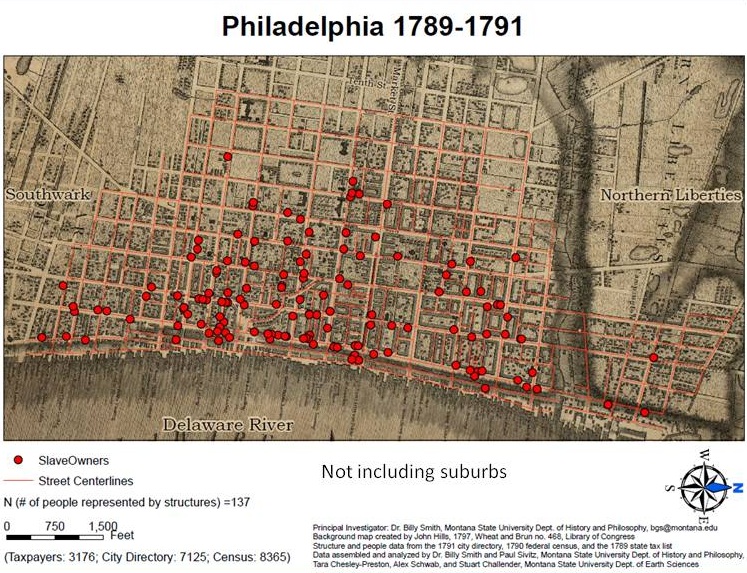

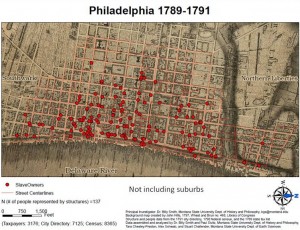

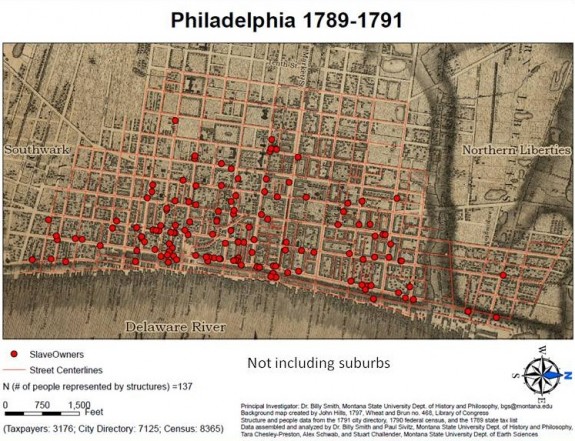

Slaves and Slave Owners. In 1780, Pennsylvania became one of the first states to pass a gradual emancipation law. A decade later, federal census takers recorded 301 slaves in urban Philadelphia, and that number continued to decline rapidly throughout the 1790s. As this map shows, slavery helped create a racially integrated city, at least as measured by residential patterns. Slave owners spread widely, with a slightly heavier concentration of them south of Market Street. Most black bound people lived in stables, attics, or basements, or occupied small out-of-the-way rooms in their owner’s home.

African American Heads of Household. Black Philadelphians congregated in two major groupings. A few blocks north of the State House (subsequently named Independence Hall), a sympathetic white Quaker was willing to rent housing to free black people. Another group settled on Fifth Street, in the city’s southwestern section.

Most free black people lived in households containing between seven and fifteen people, as compared to the 6.2 average size of all households in Philadelphia. When given a choice, African Americans seemingly decided to live with others of their own race rather than in households headed by white men, who might expect to exercise control over their lives. During the 1790s, the expanding, vibrant community of black residents established the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first free black Christian church in the Western World. The original church was an old blacksmith’s shop, which they moved to Sixth Street, in the midst of where many black free householders resided. Their neighborhood concentration surely facilitated the establishment of the church.

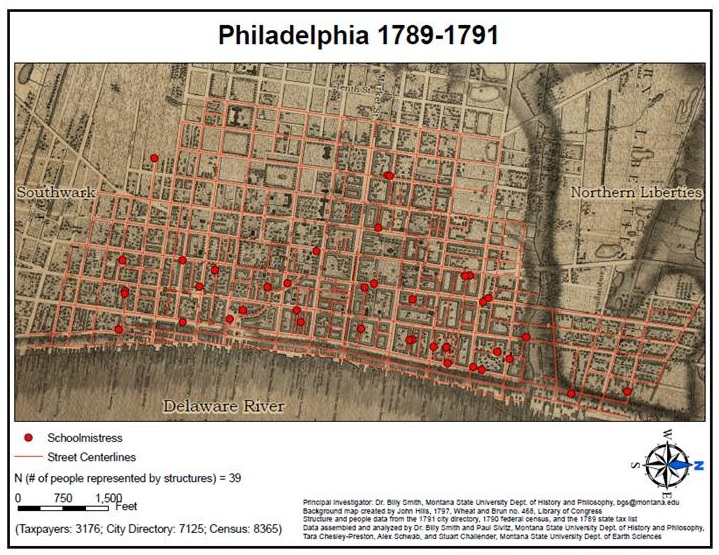

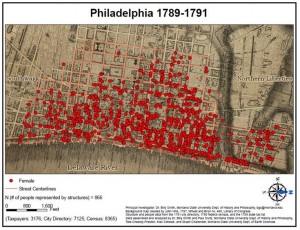

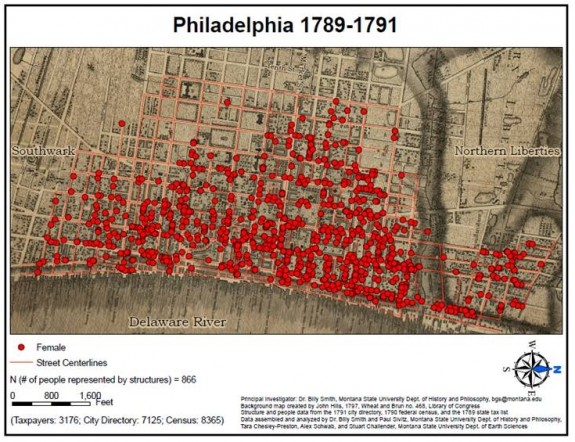

Female Heads of Household. Women headed one of every eight Philadelphia households. They spread across the city, with a slight concentration in the northern blocks where housing cost less. Employment opportunities for women, whether single or married, were limited by the society’s definition of proper gender roles. Approximately half of female household heads engaged in two types of work: (1) running a boardinghouse, inn, tavern, or lodging house, or (2) operating a small store or a huckster shop, mostly catering to other women.

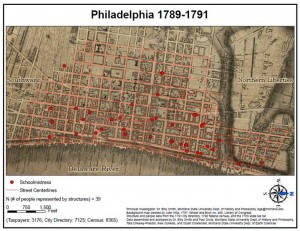

Schoolmistresses. About 10 percent of female household heads taught schools, either running their own establishments or tutoring in one of the Young Ladies’ Academies that mushroomed in urban centers after the American Revolution. The new ideal of womanhood held that women should be at least minimally educated so that they could teach their sons to be responsible citizens in the new republic. As a result, a higher proportion of women, especially those from affluent families, became literate.

One of every five female household heads produced cloth items, toiling as spinners of thread, tailors, stocking weavers, or mantuamakers. A few operated brothels, popular in a seaport city filled with numerous peripatetic males like sailors. Some household heads identified as “gentlewoman” may have been sufficiently wealthy, perhaps having inherited money from their husband or father, to not have to labor for wages. Many widows and other women who lived in families earned wages essential to keeping the household afloat as housekeepers, clothes washers, cooks, seamstresses, and hired servants.

Paul Sivitz earned his PhD from Montana State University in 2012. His research focuses on early America, the history of science, and mapping late eighteenth-century Philadelphia. Currently, he teaches at Idaho State University.

Billy G. Smith is Professor of History at Montana State University. Much of his research focuses on poorer people and runaway slaves in early America as well the experience of everyday life. Ship of Death: The Voyage that Changed the Atlantic World is forthcoming from Yale University Press.

Maps Copyright 2012, Paul Sivitz and Billy G. Smith, published with permission.

Essay Copyright 2012, Rutgers University.