South Philadelphia

Essay

From the film Rocky (1976) to the Italian Market, South Philadelphia’s image as an urban village has been entwined with Italian immigration. While South Philadelphia’s large Italian immigrant community marked the neighborhood in many ways, an array of ethnic, racial, and religious groups have resided in South Philadelphia since the seventeenth century, making its history the history of immigration and working-class striving in Philadelphia. Drawn here due to the availability of work, each group fought to carve out a space for itself by establishing homes, families, and social institutions in this neighborhood that stretches from South Street to the I-76 expressway and from the Delaware to the Schuylkill Rivers.

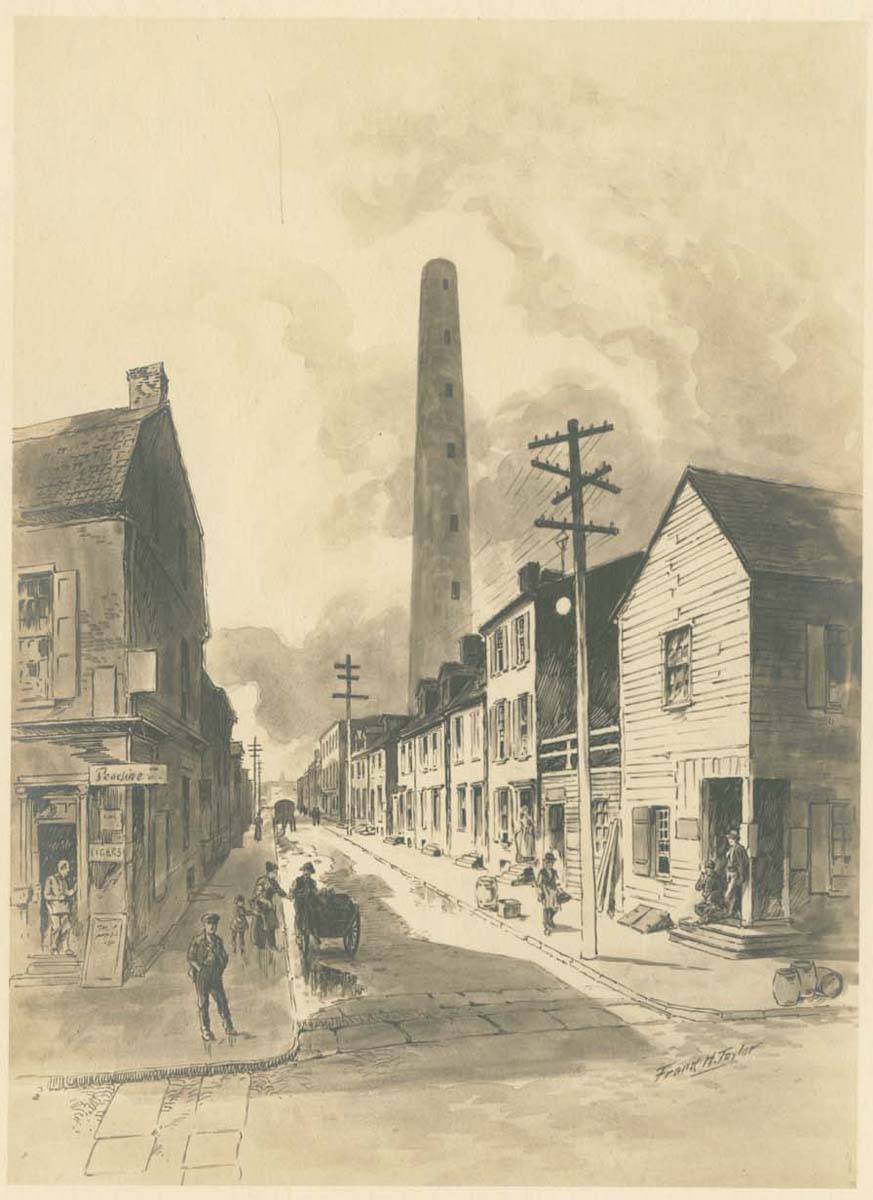

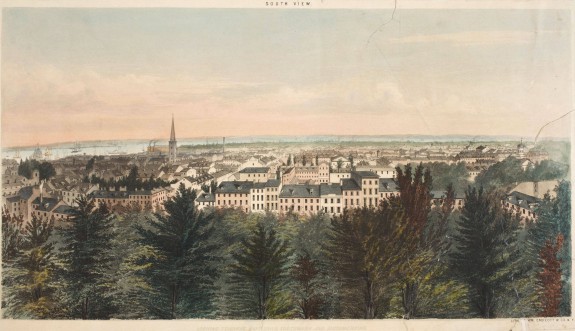

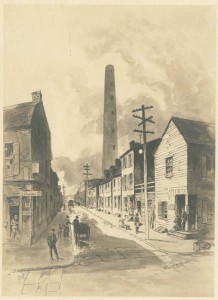

South Philadelphia’s roots lie with Lenni Lenape Indians who utilized the Delaware shoreline as source of food. European settlement began with the New Sweden colony, centered in Delaware. The second oldest Swedish church in the U.S., Gloria Dei, now known as Old Swedes Church (Columbus Boulevard and Christian Street) was built between 1698 and 1700. After a brief period of Dutch habitation, the English settled here, with King Charles II (1630-1685) granting William Penn (1644-1718) a charter for Pennsylvania in 1681. When Penn began planning Philadelphia, South Philadelphia was rural farmland outside the city center. It remained that way through the eighteenth century, made up of several separate districts including Southwark, Moyamensing, and Gray’s Ferry, names which still describe areas within the neighborhood.

As the nineteenth century progressed, the ethnic composition of South Philadelphia changed. Irish immigrants, who had been among the first settlers of Philadelphia, began to move south in the late eighteenth century, drawn by jobs like coal heaving along the banks of the Schuylkill, and they settled especially in Southwark and Moyamensing. Sharing cramped, dilapidated quarters with the Irish were free African Americans who accounted for 24 percent of Moyamensing’s residents in 1830. As nativism swept the nation, both Blacks and the Irish were targets of violence in Philadelphia, spurring the Black community to fight for civil rights in the mid-nineteenth century, with South Philadelphia as an important node. Octavius Catto (1839-71), one of Philadelphia’s first African American civil rights activists, migrated from the South and became a teacher at the Institute for Colored Youth (Tenth and Bainbridge Streets). In addition to raising regiments of Black soldiers for the Union Army in the Civil War, he, along with other activists, battled for the desegregation of the streetcar lines. Catto’s murder in 1871 after the first desegregated mayoral election made this victory bittersweet. His funeral, the largest for a Black person in Philadelphia to that time, helped accelerate the rise of the Republican Party, which ruled Philadelphia until the mid-twentieth century.

A Persistent Reputation

Even after South Philadelphia joined the larger city under the Consolidation Act of 1854, its image as an impoverished and dangerous area remained. The New York Tribune sensationally reported that the districts of Southwark and Moyamensing “swarm with these loafers, who, brave only in gangs, herd together.” Moyamensing Prison (1400 S. Tenth Street), opened in 1835, was another sign of the neighborhood’s poverty and social and literal distance from the city center. In operation until 1963, it housed everyone from a drunken Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) to serial killer H.H. Holmes (1861-1896) and Samuel Roth (1893-1974), a smut publisher whose later obscenity conviction ascended to the U.S. Supreme Court.

With the turn of the twentieth century, new immigration added even more complexity to South Philadelphia. Jewish people, for example, represented the largest foreign-born group by 1910. By 1930, they had organized several labor union headquarters and over 140 synagogues. By creating these institutions, immigrants laid claim to the neighborhood. While race, ethnicity, and religion distinguished these groups from each other, one thing they shared was class. The working class dominated South Philadelphia, though, as in all immigrant neighborhoods, some individuals rose in status to become merchants who owned stores and other operations that catered to local needs. While ethnic enclaves dotted the landscape with pockets of homogeneity, competition among ethnic and racial groups for housing and work led to racial conflict. In July 1918, a race riot in South Philadelphia resulted in four days of white violence against Blacks, leaving three people dead and hundreds seriously injured.

Although Italian immigration to Philadelphia began in the eighteenth century, it was only in the 1880s that large numbers of Italians settled here, often through the intercession of employment brokers—padrones—who brought them to the U.S. to help build the Philadelphia subway system and to work as stone cutters, masons, and fruit and vegetable sellers. Not made to feel welcome at the Irish Catholic churches, in 1852 the community established the first Italian national parish in the U.S., St. Mary Magdalen de Pazzi Roman Catholic Church (712 Montrose Street). This helped cement an Italian national identity out of the regional identities held by most Italian immigrants, who at the time of their arrival considered themselves as Abruzzese or Pugliese, rather than Italian. They forged strong social ties in South Philadelphia as they founded churches, gathered in bars, and spoke their native tongues.

Reign of Frank Rizzo

While the Italian community of South Philadelphia boasted a number of famous figures, like opera singer Mario Lanza (1921-59) perhaps the most politically influential was Police Commissioner and two-term Mayor, Frank Rizzo (1920-91). Growing up on South Rosewood Street, Rizzo capitalized on the law-and-order response that followed the urban uprisings of the late 1960s to assert community control for Philadelphia. Criticized by people of color, gays and lesbians, and progressives, Rizzo built a base of white support that included South Philadelphia but expanded beyond it by fanning fears of racial integration. For example, in 1967-68, Rizzo supported white South Philadelphians, many identifying as Italian, who pressed for closing the predominantly Black Edward Bok Vocational School (1901 S. Ninth Street) because of supposed Black violence against whites. However, in their response, the white group used racist language and attacked Black students who attended the school, suggesting that the real goal was maintaining the whiteness of the neighborhood. Black students rallied in protest, but changes increased the percentage of white students attending Bok and helped set Rizzo on his political trajectory.

During the 1970s and afterward, many Italians left South Philadelphia for the southern New Jersey suburbs. Deeply felt ties to South Philadelphia remained, nurtured through visits to family, friends, and churches for festivals, and trips to restaurants and specialty stores. Looked at in this way, South Philadelphia’s affective borders extend far past the river. Demographic change accelerated in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, continuing the neighborhood’s tradition of being an ethnic and racial patchwork. The Italian Market reflected these changes. Originally, Irish immigrants sold produce along this stretch of Ninth Street (between Wharton and Fitzwater Streets). Italian grocers displaced them, taking ownership of the area as seen in its name and marketing. By the late twentieth century, though, the Italian Market shifted again, with Hispanic and Latino-owned businesses, like tacquerias and a tortilleria, abutting Italian specialty groceries and butchers.

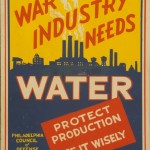

While South Philadelphia retained a distinct identity, it also forged deep ties to the region. In the early twentieth century, Italian immigrants worked as migrant laborers in the Vineland, New Jersey, fields that produced tomatoes for Campbell’s Soup, located in Camden, New Jersey. By the twenty-first century, their descendants owned the farms, which employed Mexican and Vietnamese workers to pick the produce that is sent to the large Food Distribution Center on Pattison Avenue in South Philadelphia, completing the circle. Transportation also joined South Philadelphia to the rest of the world, though the work opportunities this afforded were accompanied by serious upheaval for some. The Walt Whitman Bridge, named for Camden’s famed poet, connected South Philadelphia to New Jersey in 1957, but its construction demolished one of the poorest areas of South Philadelphia, known as “The Neck” (below Oregon Avenue, near Third Street), where residents lived a nearly rural lifestyle even though they were just a few miles from Center City. Similarly, Hog Island, once a shipbuilding facility, became the Philadelphia International Airport. Located between two rivers, residents have long counted the ports and waterways as a source of employment and large tankers and ships—some in service and some rusted to hulks—can be seen from Columbus Boulevard. The Navy Yard (4747 S. Broad Street), converted to office space, anchors the southern end of the neighborhood.

For Sports, Go South

South Philadelphians play as well as work. From the construction of Sesquicentennial Stadium in 1926 to the Spectrum in 1967, Veterans Stadium in 1971, and Xfinity Live! (Eleventh Street and Pattison Avenue) in 2012, when residents of the region have wanted to see a baseball or football game or go to a concert, they have come to South Philadelphia. This tradition dates back to the city’s founding, as Philadelphia’s first theater, the Southwark Theater (Fourth and South Streets) opened outside the city limits in South Philadelphia to evade Quaker disapproval. In a neighborhood that has enjoyed rowdy public celebrations since the nineteenth century, the best known is the Mummer’s Day Parade on New Year’s Day, when local social clubs create ornate floats and march symbolically from South Philadelphia to the heart of Center City and back. Designated an official city celebration in 1901, the Mummer’s Parade has been controversial and only in the late twentieth century did the parade ban blackface and allow women to participate.

In the first decades of the twenty-first century, South Philadelphia continued to be a neighborhood of change. According to the 2010 census, more than half of the neighborhood was white, with Blacks totaling approximately one-quarter of the population. Asians made up another 12 percent, with a growing Hispanic/Latino population of 8 percent. While Southeast Asian immigration began in the 1970s as the Delaware Valley welcomed refugees, it rose dramatically beginning in the 1990s. Like earlier immigrants, Southeast Asians created their own social worlds, including a vibrant commercial and cultural infrastructure along Washington Avenue that included large supermarkets, restaurants, and music and video stores. However, in a repetition of earlier examples of racially motivated conflict, in 2009 Southeast Asian students were attacked at South Philadelphia High School (2101 S. Broad Street), bringing to public attention tensions that had been simmering barely below the surface for years. This time, the conflict was primarily between Black and Asian students. Student and community groups rallied through this incident to advocate for better services for immigrants, much in the way that earlier settlers fought for their civil rights.

A mural by the Mural Arts Project acknowledges that immigration is the connective fiber of South Philadelphia. Called “Aqui y Alla” (1515 S. Sixth Street), the mural tells the story of the neighborhood’s growing Mexican immigrant population. Indigenous youth in Mexico created pieces of the mural, which were sent to Philadelphia and completed by Mexican immigrant youth in South Philadelphia. The continued importance of the homeland pictured in this mural helps put a visual face on the activities of generations of South Philadelphians as they built businesses, created houses of worship, founded civic organizations, and celebrated together. In this city of neighborhoods, the ties that bind South Philadelphians have as often been to faraway places as they have been to the city.

Mary Rizzo is the Public Historian in Residence at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities (MARCH) at Rutgers University-Camden. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- South Philly bodegas reflect changing neighborhoods (WHYY, July 25, 2013)

- Blatstein takes second pass at vacant riverfront land in South Philly (WHYY, April 3, 2014)

- Philly celebrates Italian culture -- with more in store (WHYY, June 17, 2014)

- Art project asks 9th Street Market vendors to get into each other’s business (PlanPhilly via WHYY, October 24, 2016)

- Judge tosses challenge to tradition of parking in the middle of south Broad Street (PlanPhilly via WHYY, September 7, 2017)