Athens of America

Essay

In the decades after American independence, the atmosphere of liberty in Philadelphia spawned an artistic spirit that earned this city its reputation as the Athens of America. Here, enthusiasm for the arts grew with the same fervor and in the same houses, streets, and shops where the seeds of political freedom had been sown and cultivated a generation earlier. Philadelphia began to grow into a vibrant, varied, and long-lasting center for arts and culture.

To many, there were clear parallels between Athens in the Great Age of Pericles (480 BC-404 BC) and Philadelphia in the early national period (1790-1840). Athens’ architectural monuments, sculpture, wall painting, pottery, furniture, literature, music, and theatre established the fundamental elements of these arts for more than two thousand years. Philadelphia was poised to take the lead artistically for America in the same way Athens inspired the ancient world.

For Philadelphians—artists and patrons alike—of the 1790s and early 1800s, the term Athens of America was (and perhaps remains) more an aspiration than an accomplishment; more a vision than a triumph. And it was as much about producing art as it was about a government that fostered artistic creation.

Following the 1788 ratification of the U.S. Constitution, many Americans were full of heady ideology as they hearkened back to the purity of the democracy of ancient Athens and the importance of the individual to the success of the whole.

Athenian Art Revival

Visually, the imitation of ancient Athenian art—broadly referred to as classical art—emerged in the mid-1700s during the archaeological excavations of the cities of ancient Greece. Europeans soon revived the arts of ancient Athens (and later Rome) as the prevailing taste, evident in everything from temple-like architecture to high-waisted columnar dresses. This embrace of classical art was uniquely timed with Americans’ enthusiasm for democracy.

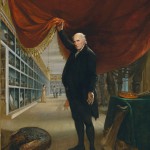

When the federal government moved to Philadelphia in 1790 for a ten-year stint, the city was ripe for the flowering of a golden age. Not only was it the most populous and most commercially active American city, the new nation’s capital was an epicenter of intellectual thought and visual expression. Philadelphia institutions were the first to provide access to literature, to encourage artistic and scientific innovation, and to display paintings publicly: consider Benjamin Franklin founding the Library Company (1731) and American Philosophical Society (1743) and Charles Willson Peale opening a portrait gallery (1782) and natural history museum (1786).

From this foundation, the city embarked on an aggressive campaign to build banks, religious and municipal buildings, theatres, art and music schools, academies, and extraordinary residences. The architecture of the new United States was identified by the Philadelphia court house, which became Congress Hall and still stands at Chestnut and Sixth Streets. The temple front, proportions, flat surfaces and arches, Greek-key cornice, and interior plaster ornament reference Greek architecture—in contrast to the State House (now Independence Hall, completed in 1753), Christ Church (completed in 1755), and Carpenter’s Hall (completed in 1773).

By the 1800s, the subtlety of Congress Hall gave way to more and more pronounced imitation, such as the creations of British-born architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764-1820): the Waterworks at Center Square (1800, now the site of City Hall), the Bank of Pennsylvania (1801), and the house and furniture of William and Mary Waln (1808). Latrobe’s protégées continued his legacy: Second Bank of the United States (William Strickland, 1816), Washington Hall (Robert Mills, 1816), the Fairmount Water Works (Frederick Graff, 1822), Girard College (Thomas U. Walter, 1833), and Nicholas Biddle’s estate, Andalusia (Latrobe, 1811 and Walter, 1837).

Classical Columns and Draperies

Sculptor William Rush progressed from carving ship figureheads to major public monuments in the classical style. Painters, led by Gilbert Stuart, Thomas Sully, and the Peale family, depicted the city’s leaders flanked by classical columns and draperies, and composed pictures based on Greek mythology and literature. Stuart recalled his time in Philadelphia in the 1790s by saying “when I resided in the Athens of America….”

The design of furniture, fabrics, upholstery, silver, and ceramics followed architecture’s classicizing trend. Where furniture once had voluptuous carving, there was low relief carving and colorful wood inlays of vases, urns, and intricate geometric patterns. Chairs had backs in the shape of vases and by 1805 wholly imitated antique Greek Klismos chairs. Upholsterers (who functioned as interior designers) contrasted sharp seat edges with flowing drapery. They modeled it on upholstery depicted on Greek pottery, which was illustrated in the catalogue of antique pottery from the “cabinet” (collection) of British antiquarian Sir William Hamilton—available at The Library Company in 1775.

Porcelain like the shell-encrusted pickle stand produced by Philadelphia entrepreneurs Messrs. Bonnin & Morris between 1770 and 1772 evolved into the lustrous smooth porcelain made at the Philadelphia factory of William and Thomas Tucker from 1826 to 1838. The Tucker’s shapes mimicked Greek pottery, with the white of the porcelain body suggesting marble.

The term Athens of America to refer to Philadelphia was used as early as 1783, though later some applied the same phrase to Boston, and towns named Athens dotted the American landscape. Henry Latrobe’s May 8, 1811, oration (in good Greek fashion) to Philadelphia’s Society of Artists is often cited as affirming the city as the Athens of America: he dreamed that “the days of Greece may be revived in the woods of America and Philadelphia become the Athens of the Western World.” Latrobe pointed out the importance of the academies and schools of art in Philadelphia—the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (founded in 1805), the Walnut Street Theatre (1809), and the Society of Artists (1811)—and their associated buildings, endowments, administrators, and teachers.

The Philadelphia Athenaeum

The Philadelphia Athenaeum — literally a place for the promotion of reading and higher learning — was founded in 1814. In The National Gazette, a writer defined the Athens of America as “A city where the public library is open three to four hours in the day.”

Could Philadelphia sustain its lofty aspiration? In 1825, a Richmond, Va., newspaper reported that “Philadelphia is determined, as far as her public buildings will effect it, to establish her claim to the title of the Athens of America.” But by the 1840s, the fervor that gave rise to Philadelphia’s claim as “Athens of America” diminished. New York — the Empire City — dominated, culturally as well as economically.

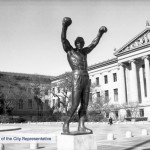

Still, the image resonated into the 1890s, when the Acropolis-like site of the reservoir for the old Fairmount Waterworks was chosen for the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Institutions created during the golden years continue to produce great painters and sculptors, and cultures from around the world add new layers to the city’s visual and performing arts.

Named by William Penn, Philadelphia — from the Greek Philos (loving) and adelphos (brother) — achieved greatness by modeling itself after Athens through placing importance on the arts. While cultural centers formed around the country, Philadelphians remain both the beneficiary and the inheritor of the pursuit to be the Athens of America. None would recognize the city without its arts.

Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley is Associate Curator of American Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Published in partnership with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, with support from the Pennsylvania Humanities Council.