American Revolution Era

Essay

The American Revolution brought upheaval to the lives of Delaware Valley residents as armies fought in battles and stripped food and other supplies from homes throughout the region. The transition from the imperial British monarchy to a republican government under the Continental Congresses and Constitutional Convention transformed Philadelphia’s legacy from a growing provincial seaport to the first capital of the United States. The region’s cultural diversity and class differences shaped the rebellion’s course, as residents embraced, opposed, or remained neutral toward Stamp Act resistance, nonimportation, and taking up arms. Population growth in Pennsylvania resulted in two new counties in the Philadelphia area after the Revolutionary War, including Montgomery (created in 1784 from part of Philadelphia County) and Delaware (created in 1789 from part of Chester County). Counties in western New Jersey and Delaware remained the same during this time period despite population increase.

The revolutionary crisis began in Philadelphia and its immediate hinterland on both sides of the Delaware River soon after the Seven Years’ War (1756-63). With a population of about twenty-three thousand, Philadelphia was the largest city in North America. Its location near the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers fostered growth of its mercantile economy. By 1765, residents had crowded along the Delaware waterfront, building neighborhoods of brick houses and mansions, taverns, warehouses, workshops, and churches including Gloria Dei (Old Swedes Church), Christ Church, and the Quaker Great Meeting House. Benjamin Franklin (1706-90), Thomas Bond (1712-84), and others established the American Philosophical Society, Library Company of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Hospital, insurance companies, and mutual aid societies.

Philadelphia served as entrepôt for exports of grain, flour, corn, beef, and pork produced on farms throughout eastern Pennsylvania, western New Jersey, and Delaware. During the eighteenth century, opportunity for land had attracted thousands of German Reformed, Lutherans, Moravians, Scots Irish Presbyterians, and Irish Catholics, expanding the region’s diversity. To repay their transportation expenses, many immigrants worked as indentured servants or redemptioners before acquiring farms or following crafts. Enslaved Africans composed approximately 8 percent of Philadelphians, compared with 2.4 percent in Pennsylvania as a whole, 20 percent in Delaware, and 4.5 percent in western New Jersey. By 1760, Pennsylvania’s European and African American population totaled about 184,000, while Delaware’s residents numbered 33,250. Western New Jersey’s population reached about 71,000 by 1772.

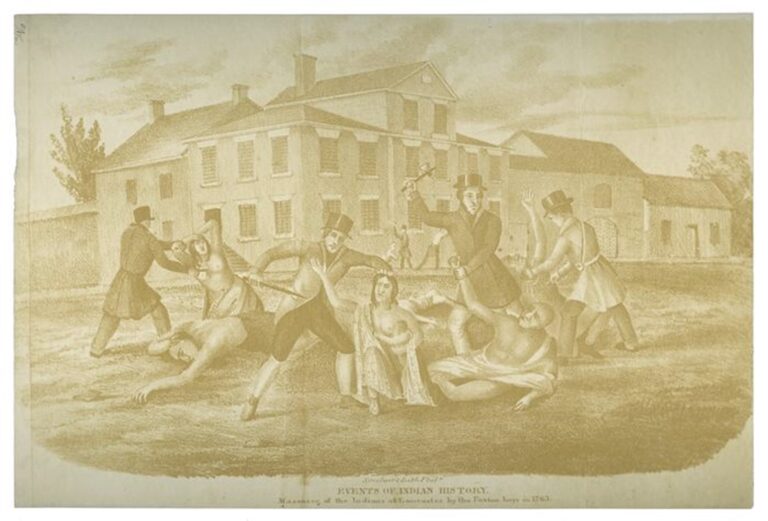

When the Seven Years’ War formally ended with the Treaty of Paris (1763), the British imperial government attempted but failed to stop white settlement west of the crest of the Appalachian Mountains with its Proclamation Line of 1763. In what became known as Pontiac’s War (1763-66), Native Americans in the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes region fought to defend their land. The war reverberated in Philadelphia in 1763-64 when the vigilante Paxton Boys, mostly Scots Irish of Lancaster County, murdered their noncombatant Conestoga neighbors and then marched against Moravian Delawares, who had taken refuge in the city. Though the Paxton Boys retreated after negotiating with Benjamin Franklin, hatred and conflict persisted as colonists continued to push west into Native territory.

Impact of Seven Years’ War

The Seven Years’ War had significant economic impacts on both the colonies and Great Britain. The Philadelphia region’s economy had surged in the late 1750s with demand for military supplies for troops in western Pennsylvania, then shrank precipitously after 1760 when the wartime theater in North America shifted to the West Indies. Though trade rebounded by the mid-1760s and grain exports increased in 1769-70 as a result of failed harvests in southern Europe, prospects for laborers, craftspeople, and merchants in the Delaware Valley remained volatile through the revolutionary period.

The economic program of Great Britain’s first minister, George Grenville (1712-70), exacerbated conditions for many colonists. Grenville believed that the provinces should help pay the huge debt Britain incurred from the war. His program to increase revenue began with the Sugar Act (1764), which lowered the tariff on foreign molasses but significantly tightened enforcement through vice-admiralty courts, which lacked juries, and writs of assistance (search warrants). The Currency Act (1764) further eroded colonial prerogatives by forbidding legislatures from issuing paper money, which had eased the chronic shortage of gold and silver.

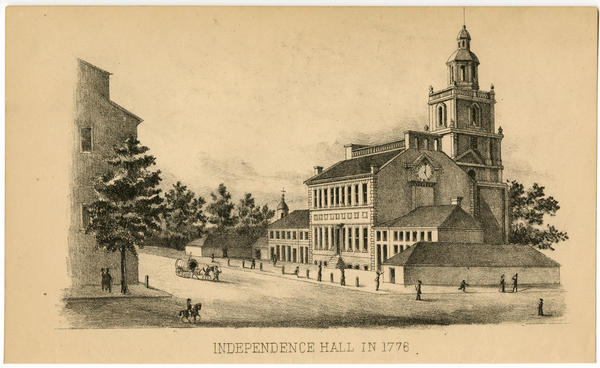

While provincial assemblies and merchants protested these measures, the Stamp Act (1765) inspired a broad-based movement that led to revolution and establishment of the United States. The Stamp Act placed taxes on all publications and official documents such as pamphlets, newspapers, deeds, wills, liquor licenses, and even playing cards. Many colonists thus recognized its potential effects, opposing the act because Parliament, rather than their representative assemblies, had imposed the tax, a blatant case of taxation without representation. In October 1765, nine of the thirteen mainland colonies sent delegates to the Stamp Act Congress in New York City, including representatives from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware. While the British government rejected the Stamp Act Congress’s petition for repeal, resistance by angry colonists prevented officials from enforcing the act. In Philadelphia, a large throng protested on September 16, 1765, at the Pennsylvania State House (later Independence Hall) and on October 5, another crowd forced John Hughes (1711-72), who had been appointed as Stamp Act distributor in Pennsylvania, to promise not to enforce the law. Philadelphia merchants joined importers in Boston and New York City to boycott British goods, which ultimately resulted in the Stamp Act’s repeal after British manufacturers petitioned Parliament. The imperial government simultaneously refused to yield its claim on power to enact laws for the colonies “in all cases whatsoever” with the Declaratory Act (1766).

The Townshend Revenue Act

In 1767, the British chancellor of the exchequer, Charles Townshend (1725-67), obtained Parliament’s approval for duties on tea, glass, paper, lead, and paint imported into the colonies. The Townshend Revenue Act was in theory an external tax rather than an internal tax like the Stamp Act, and initially raised little opposition. In December 1767, however, the Philadelphia lawyer John Dickinson (1732-1808), who possessed a plantation in Delaware, published essays that were reprinted as the pamphlet Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania (1768). He aroused protests to the Townshend Act, arguing that colonists should reject any tax for which they lacked representation and highlighted provisions of the law that reduced the power of provincial assemblies over royal governors. The colonies petitioned King George III (1738-1820) unsuccessfully, then turned once again to boycotts. While many Philadelphia merchants, concerned about economic losses, resisted nonimportation until March 10, 1769, opposition to the Townshend Act catalyzed the political alliance of artisans and mechanics with Philadelphia radicals. When Parliament repealed most of the Townshend duties, merchants in Philadelphia and other cities responded in kind by ending the boycott except on tea.

The crisis abated for several years until Parliament decided to bail out the East India Company in 1773, passing the Tea Act to give the company a monopoly and undercut the price of smuggled Dutch tea while keeping the Townshend duty. The company sent nearly 600,000 pounds of tea to the colonies, where radicals in Philadelphia, New York, and Charleston convinced the company’s agents to resign before the tea arrived. In Boston, the Committee of Correspondence headed by Samuel Adams (1722-1803) organized what became known as the Boston Tea Party to destroy about £10,000 worth of tea. Greenwich, in Cumberland County, New Jersey, was one of several towns that followed suit, destroying tea headed for Philadelphia. In response to the Boston protest, Parliament passed the Coercive Acts (1774) to close Boston’s port, impose direct Crown control of Massachusetts government, quarter British troops in local buildings, and appoint General Thomas Gage (1721-87) as royal governor.

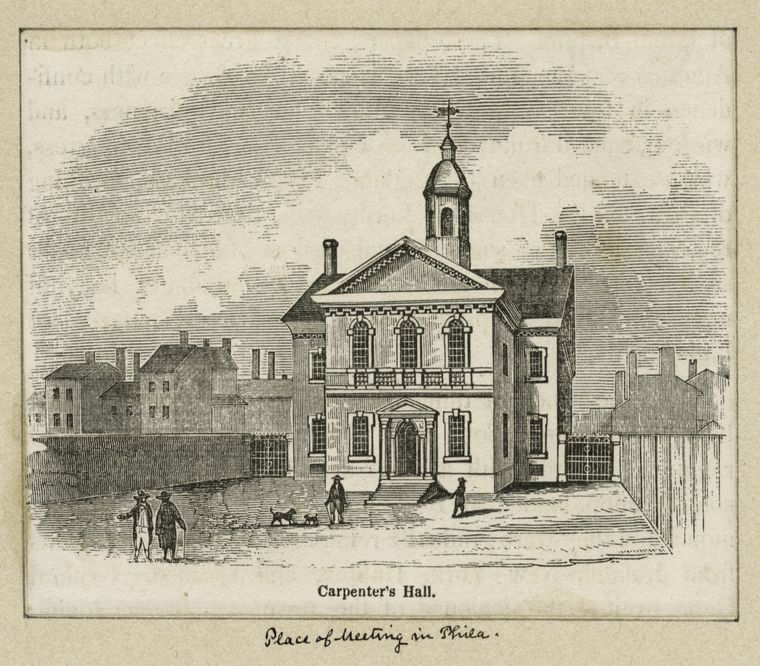

While the British aimed to isolate Boston with the Coercive Acts, in fact they pulled the colonies together as communities such as Berks County, Pennsylvania, sent relief supplies to Massachusetts. On September 1, 1774, representatives from twelve of the thirteen provinces convened the First Continental Congress at Carpenters’ Hall in Philadelphia. Among the delegates from the Delaware Valley were Joseph Galloway (1731-1803) and John Dickinson of Pennsylvania; Richard Smith (1735-1803) and James Kinsey (1731-1802) of Burlington, New Jersey; and Thomas McKean (1734-1817) and Caesar Rodney (1728-84) of Delaware. The Philadelphia radical Charles Thomson (1729-1824), who had emigrated from Ireland as a child, served as secretary to the Continental Congresses. The First Continental Congress was unprepared to declare independence, but it recommended that colonists learn “the art of war,” banned all trade with Great Britain and Ireland, and prohibited exports to the West Indies and importation of enslaved Africans. The network of local committees under the Continental Association—called Committees of Observation or Committees of Safety—quickly assumed governmental functions as they enforced the boycotts, collected taxes, and formed militias throughout the colonies, thus vesting sovereignty in the people rather than Parliament.

Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress met at the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia on May 10, 1775, several weeks after battles erupted in Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts. Congress appointed George Washington (1732-99) of Virginia as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army and authorized General Philip Schuyler (1733-1804) to organize an invasion of Canada, which ultimately met bitter defeat. Meanwhile, Congress sent the Olive Branch Petition to George III, asking him to mediate their dispute with Parliament. In response, he declared the thirteen colonies in “an open and avowed rebellion.”

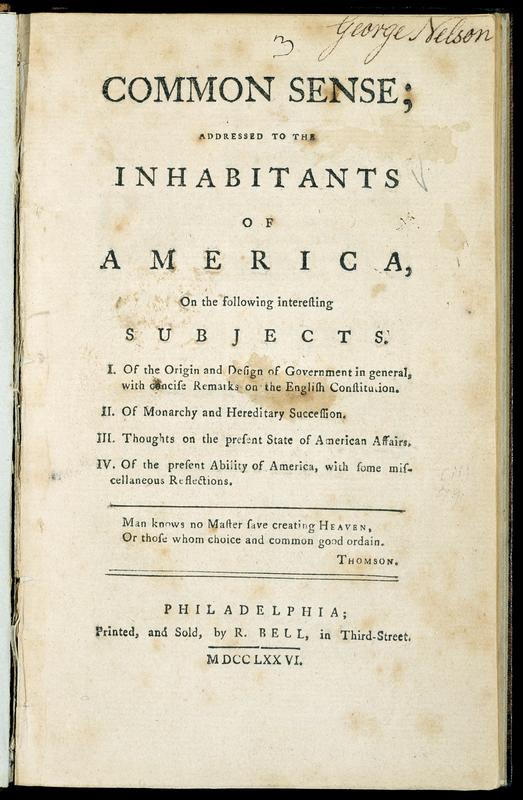

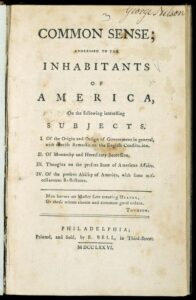

While many colonists continued to oppose independence, in January 1776 the English immigrant Thomas Paine (1737-1809) of Philadelphia helped to whip up public support with his pamphlet Common Sense, which sold more than one hundred thousand copies in several months throughout the colonies. Using plain language, Paine argued that the bloodshed in Massachusetts created an irreparable rupture with Britain and that separation was necessary to obtain assistance from France and Spain. He called for a new republic, proclaiming “‘TIS TIME TO PART . . . there is something very absurd, in supposing a continent to be perpetually governed by an island.”

As sentiment for independence grew, legislatures of some provinces, including New Jersey, authorized their delegates in Congress to approve the split, while assemblies in New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland refused. The British dispatch to New York of warships and a large army, including German mercenaries, increased support. In June 1776, Congress appointed a five-man committee to draft the Declaration of Independence, including Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) of Virginia, John Adams (1735-1826) of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman (1721-93) of Connecticut, and Robert R. Livingston (1746-1813) of New York. Jefferson drafted the declaration at his lodgings at Seventh and Market Streets, enumerating American grievances against the king and declaring the colonies independent. Congress reached a unanimous decision on July 2, 1776, when Caesar Rodney rode through the night from his home in Delaware to break his delegation’s tie, and the moderates John Dickinson and Robert Morris (1734-1806) abstained, shifting the Pennsylvania delegation to support the document.

Radicals took control of the Pennsylvania government when conservative leaders such as Joseph Galloway and William Allen (1704-80) renounced independence. In June 1776, James Cannon (1740-82) and other radicals called for a convention to draft a new state constitution, preventing Loyalists and Quakers from voting for convention delegates. The Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776 is considered the most democratic of state constitutions during the revolutionary era, establishing a unicameral legislature elected annually by a broad male electorate. The constitution extended favorable representation to Pennsylvania’s western counties, while denying political participation to Loyalists, Quakers, and other neutrals through a test oath supporting the new government.

Crafting the Articles of Confederation

In mid-July 1776, Congress started work on the Articles of Confederation, which the representatives sent to the states more than a year later, when Congress sat in York, Pennsylvania. In the Articles, each of the thirteen states held sovereignty, retaining the rights to tax and raise troops. Congress held responsibility for conducting war and foreign affairs, coining and borrowing money, supervising the post office, and negotiating boundary disputes between the states. While Congress operated under the Articles during the war, despite delay in ratification until 1781, its lack of authority to tax directly and raise troops severely hampered its ability to supply the Continental Army.

The British army and navy converged on New York City in summer 1776 with thirty-two thousand troops and supplies on 370 transports from London. They joined ten thousand soldiers under General William Howe (1729-1814) who had retreated from Boston under siege by Washington’s army. The British also sent seventy-three warships and thirteen thousand sailors to blockade and bomb American ports. Outgunned in battles in New York, the Continental Army escaped across New Jersey to eastern Pennsylvania, permitting the British to occupy and plunder New Jersey towns and farms. The Continental Congress left for Baltimore, acknowledging Howe’s goal to occupy Philadelphia. At this low point, which Thomas Paine described as the “times that try men’s souls,” Washington faced depletion of his ranks as the enlistments of many troops expired December 31, 1776. Nevertheless, his army pulled off a stunning victory by crossing the Delaware River to surprise 1,400 Hessians at Trenton on Christmas night. In January 1777, the Patriots defeated the British at Princeton after Continental soldiers extended their terms and New Jersey and Pennsylvania militias joined the fight.

While Howe retreated from New Jersey except for the area between New Brunswick and Perth Amboy, Washington set up his winter encampment at Morristown, on elevated ground to the west of the Watchung Mountains. By controlling northern New Jersey, the Continental troops could keep surveillance on the Royal Army in New Brunswick and New York City and maintain communications between New England through Philadelphia to the South. New Jersey earned the name of “Crossroads of the Revolution” as more than six hundred battles and skirmishes took place within its boundaries and on adjacent waterways, more than in any other state. Pillaging and destruction by New Jersey Loyalists and British soldiers caused havoc, but convinced the majority of state residents to support the Whigs, who kept control of the state government.

With Washington effectively blocking Howe’s route across New Jersey to conquer Philadelphia, the British forces in summer 1777 sailed around the Delmarva peninsula to the head of Chesapeake Bay. Howe failed to coordinate his plans with the simultaneous invasion of General “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne (1722-92) from Canada through the Hudson Valley to cut off New England from the other states. Burgoyne’s mission collapsed at Saratoga without Howe’s reinforcements, giving Benjamin Franklin evidence to obtain the 1778 French alliance that the United States could win the war. The Patriot forces were less successful in defending Philadelphia, as they lost battles at Cooch’s Bridge near Newark, Delaware, and at Brandywine and Paoli in Pennsylvania. The Continental Congress fled to Lancaster shortly before Howe’s army entered Philadelphia on September 26, 1777, then took up temporary residence in York. The Continental Army on October 4 attempted but failed to defeat the troops Howe deployed at Germantown, as heavy fog disrupted Washington’s complex plan of attack.

British Occupation of Philadelphia

The occupation of Philadelphia from September 1777 to June 1778 embroiled the greater Philadelphia region in war as Howe attempted to supply his troops. Washington’s army, headquartered at Valley Forge, curbed British plundering in rural Pennsylvania while the American Fort Billingsport, Fort Mercer, and Fort Mifflin blocked supply from the Delaware River. Chevaux de frise (weighted spears) submerged in the river further prevented ships from reaching the Philadelphia wharves. The British ultimately secured access to the river but only after masterful resistance by Patriot troops. On October 22, 1777, Hessian forces under Colonel Carl von Donop (1732-77) suffered heavy losses at Fort Mercer, at Red Bank in Gloucester County, New Jersey. In mid-November, after weeks of continuous bombardment, Americans evacuated Fort Mifflin on Mud Island, south of Philadelphia, then abandoned Fort Mercer as well when that position became untenable. The Royal and Patriot armies fought in many battles and skirmishes in the Philadelphia region during the British occupation, including the battle at Gloucester in which the Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834) led American forces, and the British massacre of Patriot militia at Hancock’s Bridge in Salem County.

General Howe gained little by invading Philadelphia as his soldiers occupied homes and stole food, livestock, firewood, and clothes from residents who remained in the city because they took Loyalist or neutral positions or could not afford to escape. Quakers such as Elizabeth Drinker (1735-1807), who remained neutral because of their pacifist beliefs, found life difficult under both the Patriot and British regimes. Elizabeth dealt with occupying soldiers who demanded supplies and quarters in 1777-78 while her husband Henry Drinker (1734-1809) and other leading Friends were held in Patriot custody in Winchester, Virginia. The costly Meschianza to mark Howe’s departure in spring 1778 alienated many Americans with its elaborate procession, tournament, and glamorous ball.

When the new British commander of North America, Sir Henry Clinton (1730-95), marched his army to New York in June 1778, Washington’s Continentals quickly followed. They had trained during the winter at Valley Forge under General Friedrich von Steuben (1730-94) and received much needed arms from the French. The Battle of Monmouth, at Freehold, New Jersey, ended in a draw as Clinton’s forces proceeded to New York, yet the American soldiers demonstrated considerable skill. New Jersey militia and civilians provided much greater support to Washington’s army than they had earlier in the war. With French deployment of its navy to the West Indies, the British government altered strategy to focus on the Caribbean and southern United States, where Clinton hoped to obtain help from Loyalists in Georgia, the Carolinas, and Virginia.

Beyond the battlefields, the Revolution brought turmoil as Patriot governments attempted to raise troops, supply the Continental Army and militias, and keep peace among citizens with varied sympathies and needs. Without power to tax, the Congress printed paper money that was nearly worthless by 1779. When states similarly issued paper currency and inflation soared, members of Philadelphia’s militia rallied against reputed Loyalists, then surrounded the house of James Wilson (1742-98), a congressman who opposed price controls. In the Fort Wilson Incident, militiamen exchanged gunfire with thirty men in Wilson’s house, resulting in six dead and seventeen wounded. This conflict and the militia’s protest against injustice because the affluent could pay fines to avoid the draft prompted fears of class warfare among Americans.

Divergences Among the Enslaved

Many enslaved Black people throughout the colonies took advantage of the Revolution to escape to freedom. Thousands of free and enslaved Black people fought with the Continental Army, militias, and privateers, such as the free Philadelphian James Forten (1766-1842), who at age fourteen served on the privateer Royal Louis of Stephen Decatur (1751-1808). Others sought freedom by joining British troops, eventually evacuating from the United States with Loyalists to Britain, Sierra Leone, Canada, and other colonies. With leadership of Irish Presbyterian George Bryan (1731-91), the Pennsylvania government passed the 1780 Act for Gradual Abolition, building upon the initiatives of enslaved Black people to obtain freedom and the antislavery campaigns of Quakers such John Woolman (1720-72) of Mount Holly, New Jersey; Anthony Benezet (1713-84) of Philadelphia; and Warner Mifflin (1745-98) of Kent County, Delaware. As of March 1, 1780, when the law was passed, children born to enslaved mothers would be free after they served a long period of servitude to age twenty-eight. Though the act released no one currently enslaved, it helped to inspire many individual enslavers in the Delaware Valley to follow suit, emancipating enslaved workers after a term of years. New Jersey delayed adopting a similar law until 1804, while Delaware failed to pass legislation abolishing slavery, only changing its policy in 1865 with the Thirteenth Amendment.

The Revolution had limited impact on women’s status, as the states continued to follow English common law restricting married women’s property rights. Congress and state assemblies defined office holding and suffrage as male privileges, with the brief exception of New Jersey, where female property holders could vote from 1776 to 1807. Many male revolutionaries ignored women’s contributions to the war, including those who participated in battles, served as spies, maintained the home front, and formed civic associations to assist the Continental Army, such as the Ladies Association of Philadelphia, organized in 1780 by Esther DeBerdt Reed (1746-80), and the New Jersey Association, led by schoolteacher Mary Dagworthy (c. 1748-1814) of Trenton.

Following the Fort Stanwix Treaty of 1768, in which the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) without permission ceded Delaware (Lenape) and Shawnee homelands, the Revolution further destroyed expectations of Native people to retain their territory. During the war, some Native people supported the Americans, more backed the British, while many tried to remain neutral, considering the Revolution a conflict between brothers. In the end, outcomes for Native families were similar regardless of which side they had favored, as the Continental Army in 1779 destroyed towns in the northern Susquehanna and Allegheny Valleys. By 1783, most Native people in Pennsylvania had been killed or forced to seek new homes in Ohio or New York, as Pennsylvania recognized no reservations within its borders. The Treaty of Paris (1783) further threatened their lands in the trans-Appalachian region as Great Britain yielded its territory to the Mississippi River. Some Lenapes continued to live in New Jersey, either at the Brotherton reservation in Burlington County or in independent towns such as Cohanzick in Cumberland County. In Delaware, despite serious obstacles, Lenapes and Nanticokes also sustained their communities and culture.

While the Treaty of Paris, negotiated by Benjamin Franklin, John Jay (1745-1829), and John Adams, brought hard won independence and expansive boundaries for the United States, the new nation’s economic prospects seemed uncertain. Congress owed millions of dollars in war debts to foreign countries and American citizens but had no power under the Articles of Confederation to tax. Efforts failed to obtain approval from the states for a 5 percent duty on imports. With independence, the British government cut off United States ships from access to the British West Indies, the major market for grain, lumber, and livestock from the Delaware Valley. British vessels now carried exports from Philadelphia to the British islands and returned with rum, sugar, and molasses. U.S. carriers dealt in France and its colonies, as entrepreneurs opened new routes to the Netherlands, Germany, and China. To assist merchants who had lost business during the Revolution, Philadelphia financier Robert Morris proposed the Bank of North America. Founded in Philadelphia in 1781, the bank remained solvent by pursuing a conservative lending policy to elites, thus infuriating farmers and craftspeople who also needed access to funds.

After the War, New Arrivals

Despite uncertain economic conditions in the 1780s, the Philadelphia region attracted new immigrants willing to test the benefits of a republican government. Pennsylvania created two new counties in the Philadelphia area, including Montgomery County (in 1784) with its county seat at Norristown, and Delaware County (in 1789) with its county seat, Chester.

Amid economic turmoil and protests in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and other states, leaders such as Robert Morris and Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804) sought a stronger national government. The Confederation Congress lacked funds to pay the war debt and power to end insurrections such as Shays’s Rebellion in Massachusetts. Representatives met first in Annapolis, Maryland, in September 1786 but, when only five state delegations arrived, called for another convention in Philadelphia in May 1787 to revise the Articles. After approval by Congress, the Constitutional Convention met at the Pennsylvania State House in summer 1787, as delegates debated provisions of the United States Constitution in sweltering heat behind closed windows and doors. The convention quickly moved beyond revising the Articles to create a national government composed of three branches—the bicameral legislature, independent executive, and courts—but one in which states continued to hold substantial powers. The Great Compromise (or Connecticut Compromise) resolved an impasse between large and small states, basing representation in the House of Representatives on population (including three-fifths the number of enslaved residents), and giving two seats in the Senate to each state regardless of population size. Substantial discussion focused on slavery and the slave trade, in which Northerners with antislavery sentiments yielded to Southern threats of disunion to approve the fugitive slave clause, protection of the international slave trade for twenty years, and the three-fifths clause, which gave Southern states representation in Congress for enslaved people, who could not vote.

After signing the Constitution on September 17, 1787, the delegates sent the document to the Confederation Congress, which forwarded it to the states for ratification. Approval by nine state ratifying conventions was needed for the Constitution to go into effect. Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey were the first three states to enter the Union, as Delaware and New Jersey ratified unanimously and Pennsylvania by a vote of 46-23. Georgia and Connecticut then ratified by January 1788, followed by Massachusetts, Maryland, South Carolina, New Hampshire, Virginia, and New York by late July 1788. In Philadelphia, five thousand men celebrated the Constitution’s ratification on July 4, 1788, by marching in the Grand Federal Procession to the Bush Hill estate of William Hamilton (1745-1813), with an audience of seventeen thousand men, women, and children.

During the American Revolution, as war intensified and crossed boundaries, soldiers and citizens increasingly considered themselves Americans. In Philadelphia, the Founders endorsed the egalitarian language of the Declaration of Independence “that all men are created equal.” Similarly, they crafted a republican government in the United States Constitution in which “We the People” hold sovereign power, not a king or dictator. While political culture restricted formal power to white men, Delaware Valley abolitionists offered an alternative, more expansive vision of citizenship. After President George Washington’s inauguration and the first meeting of Congress in New York City in 1789, the national government returned to Philadelphia from 1790 to 1800, a decade in which the Greater Philadelphia region continued to serve as the capital of politics, arts, and culture in the new republic.

Jean R. Soderlund is Professor of History emeritus at Lehigh University. She is the author of articles and books on the history of the early Delaware Valley, including Quakers and Slavery: A Divided Spirit (1985) and Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society before William Penn (2015), for which she won the 2016 Philip S. Klein Book Prize from the Pennsylvania Historical Association. Her latest book, Separate Paths: Lenapes and Colonists in West New Jersey, was published by Rutgers University Press in 2022.

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Links

- The American Revolution (ExplorePaHistory)

- Arch Street Project Colonial Philadelphia

- Fort Mifflin (Visit Philly)

- Valley Forge Historic Site Archives (National Park Service)

- Museum of the American Revolution Online Exhibits (American Revolution Museum)

- The Interactive Constitution (National Constitution Center)

- Ten Great Revolutionary Battlefields (American Revolution Institute)

- Revolutionary War (American Battlefield Trust)