Workshop of the World

By Walter Licht

Essay

How will they know? How will future generations of Philadelphians have any inkling that their city once thrived as a premier manufacturing center, the fine products issuing from its shops, mills, and plants prized by customers around the nation and the world?

There are few traces left of this history—abandoned factory buildings here and there—and the acres and acres of empty lots that form the landscape of decaying neighborhoods that once brimmed with industrial sites and jobs give no clues. The curious onlooker might ask: What was here? What happened? Delving into the past is to find that the decline of Philadelphia manufacture is directly related to its rise, flip sides in effect of the same coin: of the strengths and weaknesses of a particular kind of industrial system that graced the city, one that rested by and large on the production of quality goods.

A rich agricultural hinterland, an enterprising merchant community, and ready markets for the products processed and crafted in the city transformed Philadelphia into a major commercial entrepôt within a half century of its founding by William Penn in 1681. By the time that delegates convened in Philadelphia in 1776 to write the Declaration of Independence, the city had become second only to London in both the volume and value of the goods that entered and left its port. Philadelphia’s commercial fortunes plummeted, however, in the early nineteenth century as the city lost trade to its chief rival, New York. Rather than enter a long-term period of economic stagnation, Philadelphia fortunately embarked on a new direction that would mark its history for the next 150 years: prospering as a major manufacturing center.

Chronicling Philadelphia’s rise to industrial supremacy is difficult since no single invention, businessperson, event, or circumstance can be designated as a prime mover. Thousands of initiatives occurred as a steady mushrooming of varied enterprise. The individual efforts do add up to a whole, and at least four features characterized Philadelphia’s industrial structure in its heyday.

Diversity, Specialization, Skill

First is product diversity. Never a one or two-industry city, Philadelphia became known for its fine textiles and garments, boots and shoes, hats, iron and steel, metal items, machine tools and hardware, locomotives, saws, rugs, furniture, shipbuilding, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, glass, cutlery, jewelry, paints and varnishes, printing and publishing, medical instruments, and so much more.

Second is diversity of work settings. Goods were made in homes, craft shops, sweat shops, small manufactories with hand and foot-driven machinery, water and steamed-powered mills, and multidimensional plants. In their manufacture, some products even passed through several of these settings from initial processing of raw materials to final finishing.

Third is specialization in processes and products. Philadelphia manufacturers did not prosper by competing with mass producers of goods in other parts of the country, but rather by operating in niche markets fashioning high-quality wares or by concentrating in single aspects of production (in textiles, for example, separate establishments emerged respectively to spin special fibers, weave fine clothe and dye elaborate fabrics). Even in the case of Philadelphia’s famous (but relatively few) large firms, such as Baldwin Locomotive, Stetson Hat, and Midvale Steel, specialty production remained the hallmark. Baldwin rarely made two engines alike, meeting particular orders of rail carriers for locomotives with highly specific dimensions and powers; Stetson produced the finest of felt and straw hats and sold them in beautifully-made boxes with silk insides and adorned with the renowned Stetson logo; and Midvale produced a specialty grey steel and took orders for specialty castings and forgings (unlike its other Pennsylvania rivals, U.S. Steel and Bethlehem Steel).

Fourth is the prevalence of small-to-medium-sized, family-owned-and-managed manufacturing concerns that were reliant on highly skilled workforces. Large, corporate enterprises with armies of mass assembly workers did not form a part of Philadelphia’s economic skyline.

Niche Markets

A number of factors contributed to Philadelphia’s particular industrial history. An abundance of skilled labor allowed for specialty production. The absence of a powerful river-way with waterfalls initially limited the building of large-scale, fully mechanized factories. Philadelphia custom producers further chose not to compete with manufacturers of cheap, standardized products in other cities; their small size afforded a flexibility that allowed them to shift into new product lines and profit in niche markets. Finally, Philadelphia’s elite tended to invest in banks, canal and railroad construction, and mining rather than in local industry; this created a capital scarcity for manufacture in the city, another limit on large-scale ventures, and a vacuum that enterprising native-born and immigrant skilled men could fill in establishing their relatively small custom manufactories.

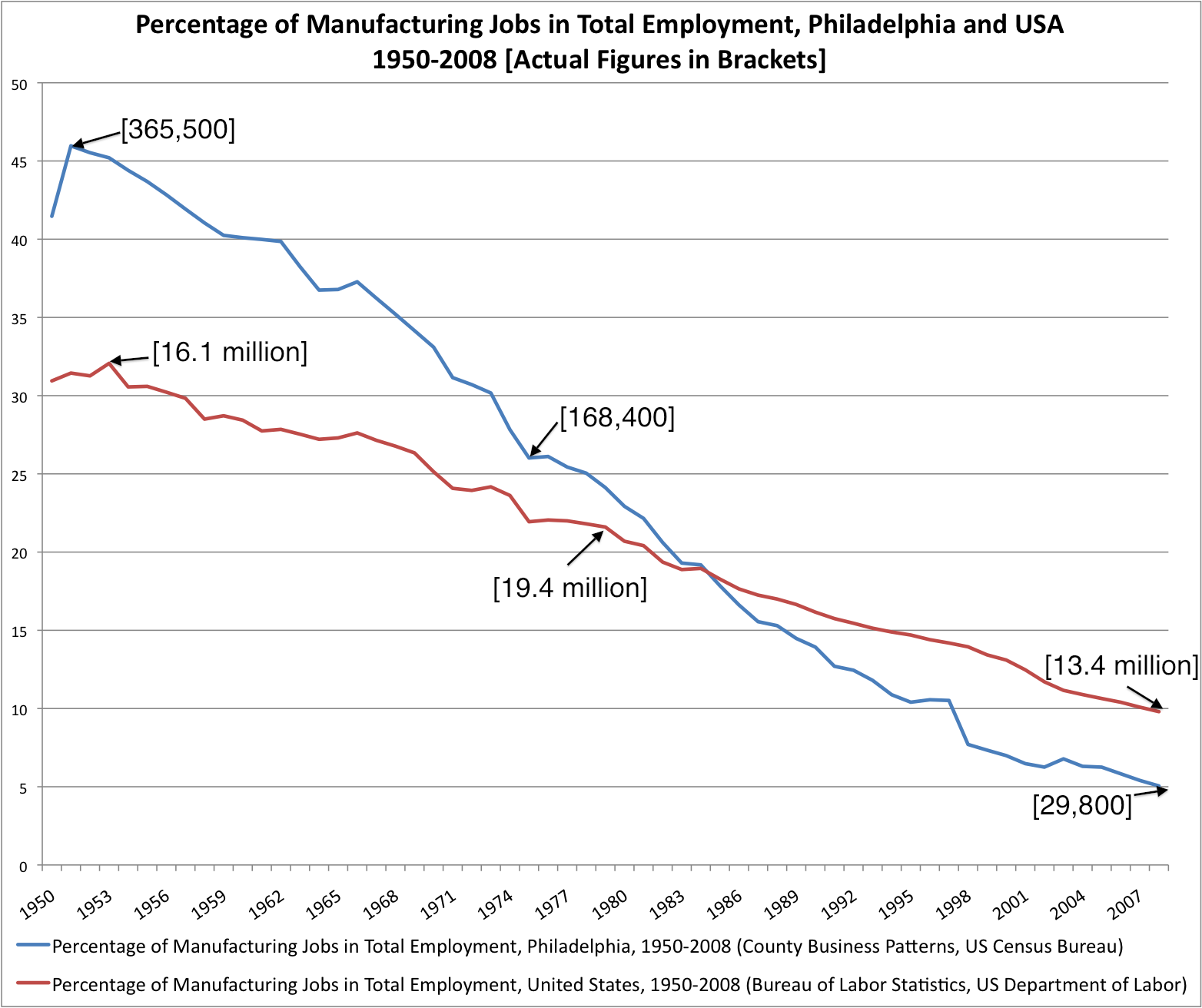

Although the first use of the label “Workshop of the World” cannot be precisely determined, by the first decade of the twentieth century, the phrase was regularly attached to Philadelphia in journals and books and in the pronouncements of business and civic leaders. However, the success and prosperity that marked Philadelphia industry crested in the 1920s when declines occurred in textile and garment manufacture and in shipbuilding—although new production of radios and electrical appliances sustained employment. The Great Depression saw retrenchments everywhere as unemployment at its peak reached more than 40 percent of the city’s work force. Military orders during World War II then boosted production, but a massive enduring decline in industrial jobs occurred thereafter. At a postwar height in 1953, 359,000 Philadelphians were employed in manufacture, 45 percent of the city’s entire labor force; in our own times, the number of industrial jobs has dramatically fallen to below 30,000, 5 percent of the total. These figures reflect the greater deindustrialization of the United States, though the downward spiral for Philadelphia far exceeded the nation as a whole; since the early 1950s, overall manufacturing jobs have declined from a high of 19.4 million to 14 million, from 32 percent of all employment to 10 percent.

As Philadelphia’s industrial ascent had a particular cast, so did the descent. Philadelphia did not lose manufacturing jobs because national corporations purchased and liquidated the facilities of local firms to undo competition; nor because financiers breezily bought, broke up and sold firms to make paper profits; nor because of foreign competition and the flight of businesses to low-wage areas in the U.S. and abroad—as happened in other American cities and regions over the course of the twentieth century. Rather, Philadelphia’s manufactories closed their doors because of changes in consumerism. Synthetic fibers, for example, wiped out Philadelphia’s famed silk hosiery trade; parquet flooring and wall-to-wall shag carpeting decimated the city’s tapestry rug industry; men stopped wearing fine felt hats to the detriment of Stetson; and cheap hardware merchandized by Sears Roebuck and other mass distributors cut deeply into the sales of the magnificently crafted and durable saws of the Disston Saw Company.

Mass production and marketing systems promoting shifts in consumer preferences to inexpensive disposal products proved the death knell of Philadelphia industry as the city’s custom manufacturers—slow, unable or unwilling to react—failed to compete with standardized producers of goods elsewhere in the county and across the globe. The loss was great not just for the city and its citizens; greater awareness and respect for workmanship and quality was lost as well.

Walter Licht is Professor of History at the University of Pennsylvania. His books include Getting Work: Philadelphia, 1840-1950 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Published in partnership with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, with support from the Pennsylvania Humanities Council.

Related Topics: Work, Commerce, and the Economy

Themes

Time Periods

Locations

- Delaware County, Pennsylvania

- Montgomery County, Pennsylvania

- North Philadelphia

- Northeast Philadelphia

- Northwest Philadelphia

- Southwest Philadelphia

- Gloucester County, New Jersey

Essays

- Sugar and Sugar Refining

- Aeronautics and Aerospace Industry

- Musical Instrument Making

- Trenton, New Jersey

- Fire Escapes

- Ceramics

- Philadelphia Contributionship

- Glassmakers and Glass Manufacturing

- Bakeries and Bakers

- Grocery Stores and Supermarkets

- Garment Work and Workers

- Fabric Row

- Saws and Saw Making

- Paper and Papermaking

- Silk and Silk Makers

- Pharmaceutical Industry

- Textile Manufacturing and Textile Workers

- Bridgeton, New Jersey

- Market Street

- Machining and Machinists

- Hospitals (Economic Development)

- Jewelers Row

- Gas Stations

- Brickmaking and Brickmakers

- PSFS

- Pacific World (Connections and Impact)

- Fashion

- Toy Manufacturing

- Boarding and Lodging Houses

- Clocks and Clockmakers

- Dream Garden

- Woodbury, New Jersey

- ENIAC

- Inner Suburbs

- Furnituremaking

- Single Tax Movement

- General Trades Union Strike (1835)

- Horses

- Spanish-American War

- Iron Production

- Norristown, Pennsylvania

- Railroad Strike of 1877

- Locomotive Manufacturing

- Deindustrialization

- Contractor Bosses (1880s to 1930s)

- Cordwainers Trial of 1806

- Shoemakers and Shoemaking

- Helicopters

- Trade Unions (1820s and 1830s)

- Tobacco

- Chemistry

- Artisans

- Korean War

- Chemical Industry

- Refineries (Oil)

- Art of Dox Thrash

- Manufacturing Suburbs

- Barbershops and Barbers

- Enterprise Zones and Empowerment Zones

- Coal

- Franklin Institute

- Radio (Commercial)

- Petty Island

- Bookselling

- Slinky

- Dentistry and Dentists

- Arsenals

- Co-Working Spaces

- Restaurants

- Commercial Museum

- Philadelphia Board of Trade

- Superfund Sites

- Brownfields Redevelopment

- Gunpowder Industry

- Automobiles

- Automotive Manufacturing

- Schuylkill Navigation Company

- Office Buildings

- Bank of North America

- Book Publishing and Publishers

- Pipelines

- Chinatown

- Printmaking

- Saturday Evening Post

- Opportunities Industrialization Center (OIC)

- Carpet Weaving and Rug Making

- Maps and Mapmaking

- Chester, Pennsylvania

- Shirtwaist Strike (1909-10)

- Canals

- Airports

- Cast Iron Architecture

- Railroads

- Duffy’s Cut

- Philadelphia Stock Exchange

- General Strike of 1910

- Tastykake

- Scientific Management

- Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC)

- Labor Day

- Industrial Neighborhoods

- World War I

- Southwest Philadelphia

- Immigration (1870-1930)

- Walking Encyclopedia: Harrowgate

- Philadelphia Plan

- March of the Mill Children

- Automats

- African American Migration

- Sullivan Principles

- Insurance

- Recording Industry

- Knights of Labor

- Immigration (1790-1860)

- Great Depression

- Immigration (1930-Present)

- Paints and Varnishes

- Printing and Publishing

- Shopping Centers

- Delaware Avenue (Columbus Boulevard)

- Food Processing

- Campbell Soup Company

- Centennial Exhibition (1876)

- Shipbuilding and Shipyards

- Flaxseed and Linen

- Industrial Workers of the World

- Banking

- Flour Milling

- Elfreth’s Alley

- World War II

- Slovaks and Slovakia

- Root Beer

- Diners

- Sports Cards

- North Philadelphia

- Northeast Philadelphia

- Northwest Philadelphia

- Bridges

- Silversmiths

- Philadelphia Regional Port Authority

- Child Labor

- Schuylkill River

- Candy and Candymakers

- Delaware River Ports

- Philadelphia AFL-CIO

Artifacts

Map

Philadelphia enacted the first municipal law mandating fire escapes on all sorts of buildings and is associated with a design innovation: Philadelphia fire tower, as seen near Thirteenth and Walnut Streets.

Glassmakers and Glass Manufacturing

An industry active throughout the region, in the nineteenth century, glassmaking continued in Millville, New Jersey, into the twenty-first century.

Baking, one of the earliest businesses in Philadelphia, ranged from small neighborhood bakeries to large companies like the Tasty Baking Company, headquartered by the twenty-first century at the Philadelphia Navy Yard.

A textile and garment district emerged on South Fourth Street during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as immigrants transformed the neighborhood into a Jewish Quarter.

Philadelphia ranked as one of the nation’s foremost saw manufacturing centers for much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. By the mid-nineteenth century a number of major saw manufacturers operated in the city, including the world’s largest, Henry Disston’s Keystone Saw Works.

Philadelphia became one of the nation's major manufacturers of silk in the early nineteenth century. The city's most well-known silk goods maker, Horstmann & Sons, was located at Fifth and Cherry Streets.

Philadelphia played a key role in the birth of the American pharmaceutical industry during the early nineteenth century. The Philadelphia College of Pharmacy (now USciences) was the nation's first pharmacy college.

Textile Manufacturing and Textile Workers

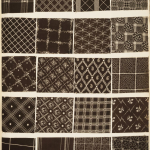

Textile production bolstered Philadelphia's economy in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Factories like Manayunk's Washington Print Works, which produced the patterns at right, shipped goods nationwide.

Between the late eighteenth and early twentieth centuries, Bridgeton was an economic stronghold for industries including glass, iron, clothing, machinery, and food processing. The Cumberland County seat and courthouse are located in Bridgeton.

Market Street, originally called High Street, was Philadelphia's earliest commercial and civic corridor and home to some of the city's most important buildings including the city's first courthouse and City Hall.

Philadelphia has a long history of machining and machinists. The Tacony Iron Works, at this location from 1881 to 1910, produced structural iron work for the tower and William Penn statue on Philadelphia's City Hall.

Hospitals (Economic Development)

Hospitals and academic medical centers have played a central role in the economies of many major U.S. cities, including Philadelphia. The site of Philadelphia General Hospital became the multi-institution Philadelphia Center for Health Care Sciences.

Jewelers Row in Center City Philadelphia emerged in the 1880s and over time became home to more than two hundred jewelry retailers, wholesalers, and craftsmen. The 700 block of Sansom Street has evolved throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and still houses many jewelry shops.

From designs evoking Greek temples built at the dawn of the automobile age to the ubiquitous utilitarian structures of the twenty-first century, gas stations have become a fixture of the Philadelphia area's landscape.

The city of Philadelphia was built with bricks, giving it an appearance many neighborhoods retained into the twenty-first century. The best quality brick clay was found in the 'Neck' between the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers.

Pacific World (Connections and Impact)

Philadelphia's connections to the Pacific World are as old as the city itself, including early participation in the China Trade and the first Japanese gardens in the United States at the Centennial Exhibition.

Philadelphia helped define the toy industry in the United States with simple yet engaging toys that became beloved by generations. Schoenhut's Humpty Dumpty Circus featured a camel, which is now housed at the Philadelphia History Museum at Atwater Kent.

Philadelphia's boarding and lodging houses provided affordable, if less than desirable, living quarters and meals to their inhabitants. They were also a means for recent immigrants and women to support themselves and their families.

Clockmakers beginning in the colonial era have made clocks that have become Philadelphia landmarks, including the Thomas Stretch clock at Independence Hall.

The renowned Dream Garden, a glass mosaic designed by Maxfield Parrish with favrile glass by Tiffany Studios, has stood in the foyer of the Curtis Publishing Building since 1916.

Initially a small farming community, Woodbury became the seat of Gloucester County and emerged as a key center for transportation, manufacturing, and the legal and medical professions. The old Gloucester County Courthouse has loomed large since opening in 1854.

The suburbs within about eight miles of the Philadelphia city limits developed their own character and cycles of prosperity and struggle. The Borough of Narberth thrives on its family atmosphere and easy commute time--less than 30 minutes by rail.

An abundance of local and imported woods, a large immigrant population, and a bustling port combined to make Philadelphia one of the centers of American furniture making in the Colonial and Early Republic eras. Many examples are in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Philadelphia helped give birth to the single tax movement, popularized by economist and Philadelphia native Henry George, whose birthplace is on South Tenth Street.

General Trades Union Strike (1835)

The General Trades Union Strike of 1835 was the nation's first general strike, prompted by coal heavers working along the Schuylkill River and demanding a ten-hour day.

The Spanish-American War had a significant influence on Philadelphia, and the USS Olympia, the flagship of the U.S. Asiatic Squadron, is permanently moored as Penn's Landing.

Southeaster Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey were prominent iron producers. Hopewell Furnace, opened in the late eighteenth century, was one of the early iron plantations.

A prime riverfront location and convenient transportation made Norristown Montgomery County's center for both industry and leisure, but its fortunes changed in the later half of the twentieth century.

The arrival on July 21, 1877 of Philadelphia militiamen, deployed from their armory at 21st and Ranstead Streets, turned the relatively peaceful railroad strike in Pittsburgh into a scene of violence and disorder.

Baldwin Locomotive dominated the steam-locomotive business. In 1906 alone, the Baldwin Locomotive Works produced 2,666 steam locomotives and employed more than eighteen thousand workers at its facilities on North Broad Street.

High labor costs, evolving technology, and changing tastes led industry to flee Philadelphia, leaving in its wake unemployment and scarred neighborhoods. At Broad and Lehigh, the Botany 500 building once was a Ford plant where soldiers' helmets were produced for WWI.

Contractor bosses dominated Philadelphia politics from the 1880s to the 1930s, enriching themselves and costing taxpayers millions annually. Building City Hall dragged on for thirty years.

Shoemaking was a large and influential occupation in early Philadelphia. In 1827, cordwainer William Heighton founded the Mechanics' Free Press and helped found the Mechanics’ Union of Trade Associations at Chestnut and Bank Streets.

Philadelphia was the cradle of the nation's rotary-wing aviation in the twentieth century. The Piasecki Aircraft Corporation, formed in 1955 and located in Essington, produced the world’s first shaft-driven compound helicopter in 1962.

Philadelphians organized trade unions and supported one of the most successful labor demonstrations in the antebellum period, the General Strike of 1835. Soon after the strike began, protesters filled the Merchants' Exchange on Walnut Street.

The early 1950s conflict between North Korea and South Korea had a big impact on Greater Philadelphia, leading to a surge in shipbuilding employment and the deaths of hundreds of local servicemen.

Greater Philadelphia was a chemical center from the eighteenth century. In 1864, Harrison Brothers opened a massive facility on Gray's Ferry Avenue. In 1917, DuPont purchased the entire Harrison Brothers enterprise.

Philadelphia emerged as a petroleum hub in the second half of the nineteenth century. In 1926, Aero Service Corporation captured aerial views of the Atlantic Refining Company in South Philadelphia.

Dox Thrash developed his skills as a printmaker under at the Graphic Sketch Club, which in 1944 became the Samuel S. Fleischer Art Memorial.

Although early industrialization took root mainly in urban centers, a substantial share of the Philadelphia region’s manufacturing sprang up in small towns outside the city. The main building of the Lee Tire and Rubber Company was built in 1909 in Conshohocken.

The history of barbering in Philadelphia reflects trends in the region and nation, with barbering dominated by marginalized groups. Joseph Cassey, a free African American, found success in early nineteenth-century Philadelphia with his white-only barbershop.

Enterprise Zones and Empowerment Zones

The enterprise zone and its successor the empowerment zone arose from policies that tackled urban decline, most notably with tax incentives for business. The Crane Arts building in Fishtown was one success.

The Franklin Institute, established in 1824, moved to its new home on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in 1934.

Philadelphia had many roles in the growth of commercial radio, including the manufacture of radios. For a few years, Atwater Kent, with a plant on Wissahickon Avenue, was the country's top radio maker.

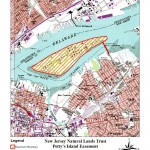

Petty Island, part of Pennsauken, New Jersey, in the Delaware River opposite the Kensington section of Philadelphia, played a significant supporting role in the economic development of the region.

Bookstores have long been an important part of the economic and cultural fabric of Philadelphia. Leary’s Book Store, one of the city’s most popular places to buy books in the nineteenth century, opened a store at this Ninth Street location in 1877.

Innovative dentists in Philadelphia helped to shape dental care, procedures, and tools. The S.S. White firm, with a factory located here in the 1880s, became a premier manufacturer of dental tools.

Dozens of co-working spaces opened (and some failed) in the early decades of the twenty-first century in Greater Philadelphia, including the pioneering Indy Hall on North Third, offering shared work space designed to foster a collaborative atmosphere

From its humble beginnings in taverns, Philadelphia's restaurant industry has grown to include some of the most important dining establishments in America. Among the oldest is Ralph's Italian on Ninth Street in South Philadelphia.

Founded in 1897, the Commercial Museum promoted the merits of international trade. Later renamed the Civic Center Museum, it closed in 1994.

The Merchants' Exchange was an early home of the Philadelphia Board of Trade, which promoted economic development.

By the late twentieth century Greater Philadelphia held some of the nation’s highest concentrations of environmentally hazardous “Superfund” sites. The Publicker Industries site was judged as Philadlephia's worst Superfund site.

The polluted land known as “brownfields” resulted from Greater Philadelphia's industrial heritage, but remediation has turned many tracts into productive sites, including PPL Park, a soccer stadium and concert venue that opened in 2010 in Chester.

Cars became a prominent force in Philadelphia's development, and by the end of World War I, Philadelphia's "automobile row" stretched from Spring Garden along North Broad Street roughly to Girard Avenue.

Car manufacturing once provided thousands of jobs in Philadelphia, including many at the Ford assembly plant opened in 1914 at North Broad Street and Lehigh Avenue. During the war, the military made helmets there.

The Schuylkill canal, built by the Schuylkill Navigation Company, connected Philadelphia with the rich natural resources of inland Pennsylvania. Part of the canal survives along the Manayunk Canal Towpath.

The fifty-eight-story Comcast Center became the city's tallest building as it was topped out in 2007, but was eclipsed in 2016 by a second Comcast office tower at Eighteenth and Arch Streets.

The original office of the Bank of North America was established at 309 Chestnut Street in 1781. In the beginning, the bank's offices were located in the home of the bank's first cashier, at the same address.

Book Publishing and Publishers

Book publishing flourished in Philadelphia in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Beginning with Benjamin Franklin, the city eventually hosted many competing publishing firms.

The discovery of oil in Titusville, Pennsylvania, and the drilling of the first successful well in 1859 led to an oil revolution. Soon pipelines emerged as a key to oil transport, and pipeline growth continues today. Some lines reach refineries at Marcus Hook, near the state line between Pennsylvania and Delaware.

Settled by Chinese migrants in the 1870s, Philadelphia’s Chinatown grew over the course of the twentieth century from a small ethnic enclave on the outskirts of Skid Row to a vibrant family community in the heart of Center City. Threatened by urban renewal in the 1960s and 1970s, Chinatown residents marshaled the redevelopment process to rebuild and expand their community over the course of the late twentieth century. This legacy of activism continued to inform struggles against gentrification and for affordable housing, education, and community self-determination. While Chinese and other Asian immigrants dispersed throughout the greater Philadelphia area, Chinatown remained as a central touchstone for Asian life in the region.

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, Philadelphia became a leading center of printmaking in the U.S., a legacy that lives on at sites such as the Brandywine Workshop on Broad Street.

The Saturday Evening Post’s circulation grew from two thousand to over three million copies an issue. This growth allowed the Curtis Publishing Company in 1910 to build a grand headquarters at the corner of Sixth and Walnut Streets near Independence Hall.

Opportunities Industrialization Center

In the 1960s, after campaigns to expose discriminatory hiring and open thousands of skilled jobs to African Americans, the Reverend Leon Sullivan founded the Opportunities Industrialization Center, a diverse program to teach marketable skills. OIC grew into an international movement that trained millions.

In its early twentieth-century heyday, Philadelphia's carpet and rug industry represented the nation's greatest concentration of factories making household and commercial floor coverings. Among them was Bromleys’ Albion Carpet Mills in Frankford.

In the nineteenth century, Philadelphia became the center of the American map publishing industry. Franklin Maps in King of Prussia carries on that tradition today.

Chester was once a booming industrial city and housed one-third of the population of Delaware County. The city supported iron works, locomotive works, paper mills, oil refineries and a ship yard in the years after the Civil War, but industrial jobs vanished in the twentieth century.

When Philadelphia's shirtwaist workers went on strike in December 1910, Philadelphia's largest shirtwaist manufacturer, M. Haber, operated at 225 S. Fifth Street.

From 1840 through 1880, a commercial district of cast iron buildings developed in Center City, helping to define the downtown of the emerging modern city, clustered from the Delaware waterfront to Twelfth Street between Arch and Pine Streets. The Smythe Stores building is now a residential building.

At Duffy’s Cut, a railroad construction site in Chester County, Pennsylvania, fifty-seven Irish immigrant railroad workers died amid a cholera epidemic in the summer of 1832 and were buried in a mass grave.

The Philadelphia Stock Exchange helped the fledgling nation raise funds to develop infrastructure for a growing industrial base and new commercial banks and insurance companies.

The Callowhill Depot built by the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company to house their fleet of streetcars.

The system of scientific management pushed companies to find the most efficient way to complete tasks. Frederick W. Taylor began to practice efficiency methods at Midvale Steel, located here, in the 1870s.

Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation

The PIDC is a nonprofit organization that is focused on supporting existing businesses in the City of Philadelphia, while attracting new industrial and commercial development through land development programs.

Compact industrial neighborhoods allowed workers to live within walking distance of factories. As industry declined in the later twentieth century, communities near shuttered factories faced economic and social challenges.

Although the United States’ involvement in World War I lasted just over a year, the conflict in Europe had a lasting impact on the Philadelphia region. The war created new opportunities for the region's industrial base, including the New York Shipbuilding Corporation of Camden.

During the national explosion of immigration that took place between 1870 and the 1920s, the Philadelphia region became more diverse as it was energized by German, Italian, Jewish, and Spanish immigrants who changed the character of the places they settled.

Walking Encyclopedia: Harrowgate

Like many neighborhoods in Philadelphia, Harrowgate, located just northwest of Kensington, experienced dramatic changes as a result of the industrial boom in the nineteenth century.

Dubbed the “Philadelphia Plan,” the program requiring federal contractors to practice nondiscrimination in hiring tested the liberal coalition formed in the aftermath of the New Deal in Philadelphia and nationally.

A three-week trek from Philadelphia to New York by striking child and adult textile workers launched on July 7, 1903, by Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, trained public attention on the scourge of child labor and energized efforts to end it by law.

People of African descent have migrated to Philadelphia since the seventeenth century. Although African Americans faced discrimination, disfranchisement, and periodic race riots in the 1800s, the community attracted tens of thousands of people during World War I's Great Migration.

Philadelphia civil rights leader Leon H. Sullivan first came to Philadelphia to pastor Zion Baptist Church. The Global Sullivan Principles represent one of the twentieth century’s most powerful attempts to effect social justice through economic leverage.

In Camden, New Jersey, the Victor Company in the early 1900s was nation’s largest manufacturer of musical recordings.

The Knights of Labor, the first national industrial union in the United States, was founded in Philadelphia on December 9, 1869. By mid-1886 nearly one million laborers called themselves Knights.

The revival of immigration to Philadelphia and its surrounding region in the early nineteenth century provided one of the most powerful elements in reshaping the city's society. The German Society of Pennsylvania assisted German newcomers in finding jobs and housing.

The region experienced severe economic hardship and fundamental change during the Great Depression. The Erie National Bank of Philadelphia, shown here, suffered a bank run in 1931.

For most of the decades since the United States’ immigration restriction acts of the 1920s, Philadelphia was not a major destination for immigrants, but at the end of the twentieth century the region re-emerged as a significant gateway.

In the U.S., Philadelphians initiated the transition from imports and small-scale preparation to large-scale manufacturing of paint materials. Samuel Wetherill Jr. erected a factory in 1809 to produce lead pigments.

Printing and Publishing (to 1950)

As Philadelphia evolved into America’s largest port city, the number of printer-publishers operating within it grew. Philadelphia’s colonial printers generally located their shops close to highly trafficked areas.

In the decade immediately following World War I, commercial real estate developers and department store owners devised new strategies to make retail shopping accessible to the area’s growing suburban communities.

Delaware Avenue (Columbus Boulevard)

Delaware Avenue played a significant role in the development of the city's maritime activity.

From the colonial era to the present, methods of processing food and the people who did the work have reflected the state of the region's economy. The Breyers Ice Cream plant was a longtime longtime landmark in Southwest Philadelphia.

Anderson & Campbell Preserve Company formed in Camden, New Jersey in 1869. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the company grew to become one of the largest food companies of the twenty-first century.

Modeled after the Crystal Palace Great Exhibition in London, the Centennial Exhibition in 1876 exhibited national pride and belief in the importance of education and progress through industrial innovation.

Philadelphia and surrounding southeastern Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey riverfront ports developed one of the greatest shipbuilding regions in the United States.

In the colonial era linen and flaxseed were fundamental to the mercantile life of Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley. Philadelphia's linen and flaxseed market extended from the farthest point of settlement, Fort Pitt, to the fields of England and Ireland.

Industrial Workers of the World

In the early 1900s thousands in greater Philadelphia belonged to the IWW. Local 8, which organized the city’s longshoremen, was the most powerful and racially inclusive branch in the Mid-Atlantic.

As early as the 1650s, industrious farmers produced enough wheat not only to sustain themselves but also to send a surplus to market. For farmers in the city’s hinterland, the center of any rural community was the “custom” grist mill.

Nestled between Second Street and the Delaware River, thirty-two Federal and Georgian residences stand as reminders of the early days of Philadelphia.

World War II, which created change for industries, populations, and politics in many urban areas in the United States, had a transforming effect on the Philadelphia region.

Slovak immigrants made important contributions to Philadelphia industries from iron and steel to leather and textiles. Many Slovak artisans did wirework for the city at factories such as this now-converted location on Race Street.

Sports card collecting has strong ties to Philadelphia, where three companies--American Caramel, Fleer Corporation, and Bowman Gum--were pioneers. Fleer's final plant before it closed was on Tenth Street in the Olney section.

The Delaware River sits at the center of the history and development of Philadelphia and the surrounding communities.

Timeline

Related Reading

Heinrich, Thomas R. Ships for the Seven Seas: Philadelphia Shipbuilding in the Age of Industrial Capitalism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

Licht, Walter. Getting Work: Philadelphia, 1840-1950. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992.

McKee, Guian A. The Problem of Jobs: Liberalism, Race, and Deindustrialization in Philadelphia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Silcox, Harry C. A Place to Live and Work: The Henry Disston Saw Works and the Tacony Community of Philadelphia. University Park: Penn State Press, 1994.

Scranton, Philip. Proprietary Capitalism: The Textile Manufacture at Philadelphia, 1800-1885. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Scranton, Philip and Water Licht. Work Sights: Industrial Philadelphia, 1890-1950. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986.

Sidorick, Daniel. Condensed Capitalism: Campbell Soup and the Pursuit of Cheap Production in the Twentieth Century. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2009.

Related Collections

Hagley Library, 200 Hagley Road, Wilmington, Del.

Special Collections Research Center, Temple University, Charles Library, Philadelphia.