Colonial Era

Essay

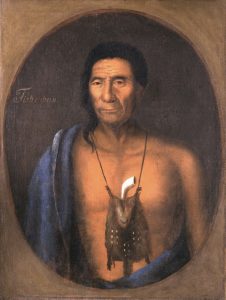

When Lenape Indians in July 1694 crossed the Delaware River from New Jersey to meet with Pennsylvania government officials, they represented a people whose homeland became the Greater Philadelphia region: southeastern Pennsylvania, central and southern New Jersey, and Delaware. Despite their decline in population from European diseases, the Lenapes remained strong. They told the Pennsylvanians that while many Lenapes “live on the other side of the river [in New Jersey], yet we reckon ourselves all one, because we drink one water,” the Delaware and its tributaries. Since the 1670s, English settlers had imposed political divisions on the more open Lenape homeland, most obviously with the boundary along the river separating West New Jersey from Pennsylvania and the Lower Counties (Delaware). But while these political divisions gained potency as colonial elites developed legal and political structures, the Delaware Valley in many ways remained integrated economically and socially as its residents exchanged goods and traveled readily across borders.

When Europeans arrived in the Delaware Valley in the early seventeenth century, Native Americans had lived there for at least ten thousand years. The Lenapes lived in autonomous towns on creeks flowing into the Delaware River and along the Atlantic coast near Delaware Bay. The river united the territory of Lenape people such as the Armewamese and Cohanseys who possessed land on both banks.

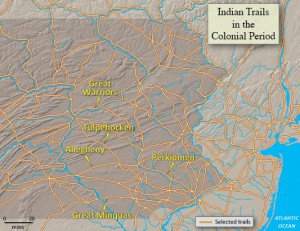

Because Lenapes traveled frequently by canoe, they viewed rivers and streams as highways rather than obstacles. They also built trails across the region by which they traveled from agricultural towns where they raised corn and other crops to hunting, fishing, and gathering areas in the Pine Barrens, Atlantic shore, Lehigh Valley, and central Delaware. The Lenape trails linked with pathways of neighboring Munsees to the north up into southern New York, Susquehannocks to the west in the Susquehanna Valley, and Nanticokes of Delaware and Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Lenape towns lacked palisades (unlike those of the Susquehannocks and Iroquois), reflecting the Lenapes’ efforts to maintain peace with their neighbors and more distant nations.

Successive European Settlements

Starting with Dutch explorers who arrived about 1615, successive groups of European colonists built settlements on both sides of the Delaware River, sometimes adjacent to Lenape towns. The natives welcomed European traders, granting permission in 1624 for a short-lived Dutch settlement on Burlington Island and two years later permitting construction of Fort Nassau at Arwamus (later Gloucester, New Jersey) opposite the future site of Philadelphia. To facilitate exchange of furs and Indian corn for European goods, the natives and Dutch colonists developed a trade jargon based on Unami, the Lenapes’ Algonquian language.

The Dutch trade precipitated war from 1626 to 1636 between the Lenapes and Susquehannocks, who sought to control the Delaware River as a market for Canadian furs. The war ended with an agreement that while the Lenapes retained ownership of the land, both groups could trade in the region. Violence also flared in 1631, when Lenapes destroyed a Dutch plantation called Swanendael near Cape Henlopen at the mouth of Delaware Bay. It seemed to the natives that the Dutch were shifting their priorities from trade to plantation agriculture similar to the English colonists in the Chesapeake Bay region who murdered Indians and expropriated land. The Lenapes and Dutch made peace when the Dutch captain David de Vries (1593-1655) arrived in late 1632.

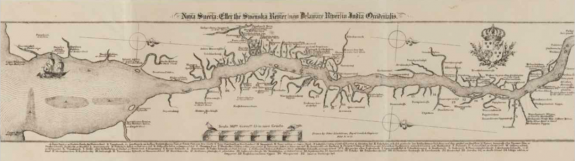

Over the next half century, with the legacy of Swanendael, Lenapes controlled the lower Delaware Valley, accepting European trade goods in exchange for small parcels of land for forts and farms, but not plantation colonies. In 1638, the Lenapes permitted Sweden to establish a colony at Christiana Creek (Wilmington, Delaware), while also trading with merchants from New Netherland and New England. Though the Lenapes rejected efforts by Swedish Lutheran missionaries to convert them to Christianity, the natives forged a special friendship with the colonists of New Sweden beginning with the 1654 treaty with Governor Johan Risingh (c. 1617-72), in which each side promised to warn the other if they heard of impending attack by another people.

By the mid-seventeenth century, the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, later the site of Philadelphia, became the region’s commercial center. As the Dutch and Swedes competed to buy lush beaver pelts that the Susquehannocks obtained from Canada, Lenapes built six towns from the Delaware to the falls of the Schuylkill to be near the terminus of trade. The Swedish engineer Peter Lindeström (d. 1691) praised the area for its beauty, fresh water springs, fruit trees, and wildlife.

Defeat of the Dutch

After New Netherland defeated New Sweden in 1655, the Lenapes, Swedes, and Finns solidified their alliance to resist heavy-handed Dutch authority; after 1664, when troops of James, Duke of York (1633-1701) defeated the Dutch, the natives and colonists fought English efforts to expropriate their land. In the late 1660s, many of the natives left their towns on the west bank of the Delaware to join Lenape communities in New Jersey. Though most European colonists lived in the area extending from New Castle (Delaware) to the Schuylkill River, Dutch, Swedish, and Finnish colonists also moved to southwestern New Jersey, purchasing land from the natives.

Despite generally good relations between Native Americans and Europeans in the lower Delaware Valley, the Lenapes there declined steadily from smallpox, influenza, measles, and other diseases. In 1600 they had numbered an estimated 7,500; by the 1650s their population decreased to about 4,000, and to about 3,000 by 1670. Still, in that year, the European population was only 850, as the memory of the Swanendael attack successfully deterred large-scale colonization.

The balance of population between natives and immigrants began to shift in the mid-1670s, on both sides of the Delaware River. In 1664, though the Lenape sachems believed the river united their homeland, the English crown drew political borders, most prominently between West New Jersey and the west bank. These borders, at first only figments in charters and on maps, gradually took force in the 1670s and 1680s as thousands of English settlers flooded in. The provincial and county boundaries that English colonialists drew across the more open Lenape landscape assumed real political and legal meaning.

The organizers of West New Jersey and Pennsylvania were members of the Society of Friends, a religious group founded in England around 1650 that repudiated many of the practices of the established Church of England (Anglican). The Friends believed that the inner Light of Christ could enter any person without the intervention of priests and bishops. The Quakers endured imprisonment, physical assaults, and fines in their home countries for holding worship services and refusing to take oaths or pay tithes to support the established church.

Quakers in New Jersey

Friends established West New Jersey through a series of complicated financial deals, lawsuits, and political battles that continued to plague the colony until the crown revoked the proprietorship in 1702. The English Quaker John Fenwick (c. 1618-1683), who claimed one-tenth of the colony, founded Salem in 1675, selling 148,000 acres to about fifty purchasers. The Friends entered a country dominated by Lenapes where some Europeans, mostly Swedes, Finns, and Dutch, had lived for fewer than ten years. Fenwick promptly purchased land from the Lenapes of the region—the Cohanseys—with whom he maintained good relations. Deeds of 1675 and 1676 specified that Fenwick would receive territory, “excepted always … the plantations in which [the natives] now inhabit,” in return for cloth, rum, guns, and other items.

Another English Friend, Edward Byllynge (c. 1623-1687), and three Quaker trustees, including William Penn (1644-1718), initiated plans for settling the remaining 90 percent of the colony. When the ship Kent arrived in 1677, the Lenapes, Swedes, and Finns offered the 230 Burlington colonists food and shelter despite worry about the increasing numbers of new immigrants. Swedish and Finnish interpreters facilitated their purchase of land from the Lenapes. As had earlier settlers, the Burlington colonists brought smallpox that killed many natives. An estimated 1,760 Friends settled in West New Jersey by 1682, taking up land from the Falls of the Delaware (later Trenton, New Jersey) south toward Salem.

The West New Jersey Concessions (1676) explained the process for distributing land, granted religious freedom and trial by jury, was unusually democratic in calling for an annually elected general assembly, and described a plan for mediating disputes between natives and Europeans. The Duke of York delayed implementation of the Concessions by not transferring until 1680 the right of government to Byllynge, who then renounced the Concessions by becoming governor, an office not included in the document. Though the Concessions failed to become the official constitution, many of its provisions, including the elected assembly, religious freedom, and trial by jury, became West New Jersey law.

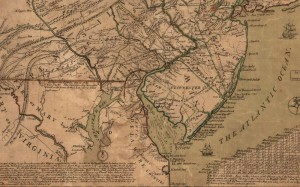

As colonists set up farms and towns along the Delaware River and its tributaries from the Falls to Cape May, the assembly created four counties in the 1680s and 1690s: Burlington, Gloucester, Salem, and Cape May. Because the provincial government remained factionalized and unstable, county courts took responsibility for governing and enforcing laws. The proprietary government dissolved in 1702 when the proprietors of both East and West New Jersey surrendered their right to govern to the English Crown to create the unified royal province of New Jersey. The new province elected an assembly of twenty-four members, equally divided between the eastern and western divisions, and shared its governor with New York until 1738, when New Jersey obtained its own royal executive.

Penn’s Charter, 1681

William Penn received his charter for Pennsylvania from Charles II (1630-85), the English King, in March 1681 and proposed a model society founded on principles of peace and religious liberty. He made specific plans to build a great city named Philadelphia, in a grid pattern with large lots on the Delaware River, to serve as the focal point for surrounding townships. He also pledged to treat the Native Americans equally and demanded that “no man shall . . . in word or deed, affront or wrong any Indian.” During 1682-1684, the first of his two two-year visits to the colony, Penn systematically purchased land in southeastern Pennsylvania from the Lenapes, paying at least £1,200 in goods, with the assistance of Swedish and Finnish interpreters.

Offering sanctuary from persecution to members of many religions, the proprietor also expected to succeed financially by selling land and collecting quitrents (annual taxes on acreage) to defray the ongoing costs of colonization and provide his family an income. He quickly recruited thousands of colonists from northwestern England, London and its environs, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Germany, and Holland. While many people who immigrated during the first decades were Quakers, new settlers also included Anglicans, Baptists, Presbyterians, Roman Catholics, Mennonites, and other sects who joined the Dutch Reformed and Swedish Lutherans already in the region. Most colonists were farmers, artisans, laborers, and their families. Prosperous Quakers who purchased large acreages soon dominated Pennsylvania society and politics, though some Swedes, Finns, and Dutch continued to hold public office. While Penn created no established religion, the Friends controlled the government through much of the colonial period.

Before sailing to his colony in 1682, Penn developed his Frame of Government that provided for a governor, and a provincial council and assembly to be elected by free male taxpayers of the province. An assembly of settlers amended the constitution in 1683 and over the next eighteen years the legislature made additional changes to assume greater power. The colony’s final constitution, the Charter of Privileges (1701), created a powerful unicameral assembly that could initiate and pass legislation subject to the governor’s approval. The Charter of Privileges also confirmed religious liberty to everyone who believed in “one almighty God” and extended the right to hold office to all Christian men, not just Anglicans or Quakers.

Lower Counties Provided Sea Access

Because Pennsylvania lacked direct access to the Atlantic Ocean, Penn sought rights to the three Lower Counties (the area of the later state of Delaware) from the Duke of York. The Quaker proprietor received deeds in 1682 to New Castle, Kent, and Sussex Counties, which remained separate from the counties of Chester, Philadelphia, and Bucks that he established in Pennsylvania, with the boundary set twelve miles north of the town of New Castle. Despite this colonial border, the Lower Counties and Pennsylvania shared a governor and at first elected representatives to one assembly that met alternately at Philadelphia and New Castle. The Swedish, Finnish, Dutch, and English inhabitants of the Lower Counties quickly felt overpowered by the Quaker government in Philadelphia and wanted local control because of divergent economic interests and the refusal of pacifist Quakers to accept the need for military defense. With Delaware’s long coastline facing the Atlantic Ocean and Delaware Bay, residents felt vulnerable to pirates and enemy attack. Delaware obtained its own assembly in 1704 but continued to share a governor under the Penn proprietorship.

Since the late 1660s, English settlers—many with enslaved Africans—had moved to the Lower Counties from Maryland to join the predominantly Swedish, Finnish, and Dutch population. The Delaware economy was primarily agricultural, with exports in tobacco, pork, and corn to the West Indies, England, and Scotland. The colony sustained several attacks from Maryland, which claimed on the basis of its 1632 charter that Delaware fell within its bounds. The dispute with Charles Calvert, Lord Baltimore (1637-1715) dogged William Penn, who sought evidence from old maps and Dutch documents to protect his ownership of the Lower Counties and Pennsylvania. Ironically, the 1631 founding of Swanendael at Cape Henlopen—despite the Lenapes’ prompt destruction—demonstrated prior European occupation on the Delaware before Baltimore’s grant. The Penns’ boundary dispute with Maryland continued until the mid-1760s, when the survey of the Mason-Dixon line also finalized the border between Pennsylvania and Delaware.

Even as Penn, the West New Jersey Proprietors, and their surveyors drew provincial, county, and local boundaries across the Delaware Valley, the increasing European population developed cohesive economic and social connections much like the Lenapes who reckoned themselves “all one.” By 1700, West New Jersey had approximately 3,500 settlers, while Europeans numbered 18,000 in Pennsylvania and 2,200 in the Lower Counties. Dispersed farms across the countryside produced wheat, corn, rye, barley, tobacco, fruit, and vegetables, and raised cattle, pigs, and fowl. The small port towns of Greenwich, Salem, Gloucester, Burlington, Bristol, Chester, New Castle, and Lewes collected and shipped agricultural produce, deer skins, furs, lumber, and wood products mostly to Philadelphia but in some cases directly to other ports in North America, the West Indies, and Europe.

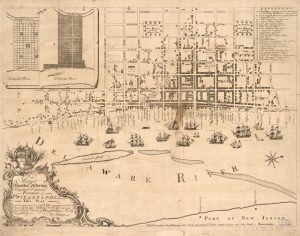

Philadelphia as Cornerstone

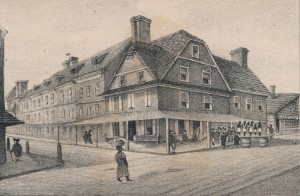

Most important to integrating the Delaware Valley was William Penn’s planned city, Philadelphia. Along with religious liberty, peaceful conflict resolution, and representative government, the city was Penn’s most significant achievement. Built upon the earlier commercial hub near the confluence of the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers, Philadelphia grew quickly from immigration and commerce. Within a decade of its founding, the city had an estimated population of two thousand; by 1730 more than seven thousand people lived there and by 1765 about twenty-three thousand, making it the largest city in North America. Despite Penn’s plan for ample lots stretching two miles from the Delaware to Schuylkill River, residents quickly clustered along the Delaware waterfront to participate in the growing mercantile economy. By the 1760s, Philadelphia was a dense urban space of brick houses and mansions, small dwellings in crowded alleys, warehouses, workshops, churches, and taverns. Some notable structures included Gloria Dei (Old Swedes Church), Christ Church, the Quaker Great Meeting House, Pennsylvania State House (later Independence Hall), and Pennsylvania Hospital.

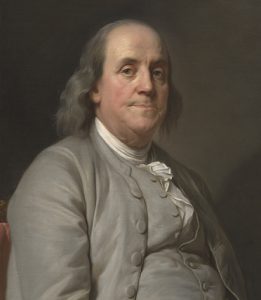

As the center of Pennsylvania government and Delaware Valley commerce, Philadelphia drew talented people from throughout the region, North American colonies, and Atlantic World. The city’s population and financial base supported innovation in science, medicine, printing, public welfare, the humanities, and arts. The list of organizations founded by people such as Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) testified to the colonial city’s vitality: American Philosophical Society, Library Company of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Hospital, College of Philadelphia and its Medical Department (later the University of Pennsylvania), arboretums, insurance companies, and mutual aid societies.

The rural Delaware Valley population also grew quickly, especially Pennsylvania with a European and African American population of 52,000 in 1730 and 184,000 in 1760. The large geographic size of Pennsylvania, with room for expansion to the north and west, helped to propel its dynamic growth. Between 1729 and 1752, five new inland Pennsylvania counties joined the ten original and two additional West Jersey counties along the Delaware River. Thousands of German-speaking and Irish immigrants crossed the Atlantic Ocean during the eighteenth century, entering through the ports of Philadelphia and New Castle. German Reformed, Lutherans, Moravians, Scots-Irish Presbyterians, and Irish Catholics added to the region’s diversity. Many immigrants served first as indentured servants or redemptioners to pay the cost of their passage, then built farms or followed crafts. While some stayed in the Quaker City, many migrated to rural areas in the Lehigh Valley and western Pennsylvania, from which some continued their journey south into western Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas. German and Irish newcomers also settled in northwestern New Jersey, helping to push West Jersey’s population growth from 14,380 in 1726 to 71,000 in 1772. Some Irish immigrants stayed in Delaware as its population expanded to 33,250 in 1760.

Delaware Valley’s Ideal Conditions

Immigration and an abundant environment interacted to fuel strong economic growth in the Delaware Valley. Its mild climate and productive soils offered ideal conditions for raising wheat, which as grain and flour led exports from Pennsylvania, West Jersey, and Delaware to the West Indies, New England, and southern Europe. Philadelphia merchants also sent corn, beef, and pork to the Caribbean, thus provisioning the brutal slave regimes of the sugar islands. From the 1730s, flaxseed became an important export to Ireland, where farmers used the seed to grow flax for high quality linen that they traded back to Philadelphia. Delaware Valley merchants also financed iron furnaces and forges in southern New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. Beginning in 1716, ironmasters produced iron stock that local artisans used to make goods such as pots, stoves, nails, tools, and wheels. Iron also became an important export after 1750.

Enslaved Africans served significantly in the region’s workforce yet slavery was never as dominant in West Jersey and Pennsylvania as in the southern plantation colonies and West Indies. Though the Dutch and Swedes brought a few enslaved people prior to 1680, the English slave trade developed particularly in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries as part of the larger Atlantic economy. In Pennsylvania, in 1684 the ship Isabella quickly sold 150 Africans to new colonists eager for workers to help build their houses, businesses, and farms. Along with servants and free laborers, enslaved Africans were especially important to Philadelphia employers. From 1691 to 1720, an estimated 10 to 17 percent of the city’s population was enslaved, and for the rest of the colonial period 8 percent of Philadelphians lived in bondage. Slavery was less substantial in rural Pennsylvania, where immigrant servants provided a great deal of labor. In 1750, slaves comprised 2.4 percent in Pennsylvania overall compared with 4.5 percent in West Jersey and 20 percent in Delaware. Unlike the plantation colonies and New England, enslaved Indians were a very small part of the Delaware Valley workforce. Although colonists imported a few enslaved Native Americans from South Carolina early in the eighteenth century, regional peace prior to the 1750s and strong Lenape resistance to slavery prevented enslavement of local natives.

For Europeans and enslaved Africans in Pennsylvania, life expectancy varied considerably between urban Philadelphia and the countryside. Whereas the rural death rate was an average of 15 per thousand people each year, the death rate for white city dwellers was 46 per thousand and even higher for blacks, averaging 67 per thousand per year. Reasons for higher urban mortality included the illnesses brought on disease-ridden ships; the higher vulnerability of immigrants and imported slaves to diseases such as measles, smallpox, and influenza because of weakened health; and poor nutrition, crowded housing, and inferior sanitary conditions in the city. Deaths were high among infants, children, and women in childbirth. Though natural population increase began in Philadelphia in the 1760s when mortality rates declined, immigration remained the most important factor in the city’s demographic growth.

Quaker Beliefs Distinguished the Region

Quaker belief in the equality of all people before God helped to generate social practices that distinguished the Delaware Valley from other parts of colonial America. Unlike restricted female roles in many religions, women Friends took responsibility as ministers and moral guardians in their communities. Quaker parents paid close attention to keeping their children within the religion while offering them considerable freedom, among Friends, in choice of marriage partner. Consistent with Pennsylvania’s commitment to religious liberty, the colony avoided a rigid marriage code and instead allowed couples to marry according to the rituals of individual denominations. This resulted in more flexibility than the legislators probably intended, with some couples taking vows at home, others choosing not to marry formally, and, if a relationship failed, opting to self-divorce. Philadelphia women gained substantial freedom in an environment of cultural diversity and economic opportunity.

Though many affluent Quakers held African people as slaves, egalitarian ideals fostered the antislavery movement among Delaware Valley Friends. Abolitionists hailed from throughout the region, including William Southeby (d. 1722), Benjamin Lay (1682-1759), and Anthony Benezet (1713-84) of Pennsylvania; John Woolman (1720-72) of West Jersey; and David Ferris (1707-79) of Delaware. Resistance by enslaved Africans and the gradual growth of abolitionist sentiment after 1688, when Germantown Friends petitioned Philadelphia Yearly Meeting against slavery, facilitated the decline in slaveholding and rise of the free black community in Philadelphia and rural Pennsylvania, especially after 1750. In West Jersey, because of its high proportion of Quakers, slaveholding was less significant (4.5 percent) than in East Jersey, where about 12 percent of the population was enslaved. In Delaware, while Quaker influence helped to diminish slaveholding, slave owners prevailed politically, preventing adoption of a gradual abolition law similar to acts passed by Pennsylvania in 1780 and New Jersey in 1804.

As early as 1684, William Penn faced challenges to his “holy experiment” in consensual government and peace from Friends who opposed civil authority, settlers of other religions who despised Quakers, and Lenapes who watched immigrants and their descendants spread out across the land. Economic downturns increased unemployment and misery among working families, leading to popular discontent. Colonists seeking opportunity moved westward in Pennsylvania and northward into the Lehigh Valley and northwestern New Jersey, taking most of the Lenapes’ remaining land. In the early eighteenth century, the West New Jersey Council of Proprietors and their counterparts in London, the West Jersey Society, purchased large tracts on the east bank of the Delaware north of the Falls, opening this territory to settlers. Europeans also filtered into the remaining unpurchased area on the western side of the river in Bucks County.

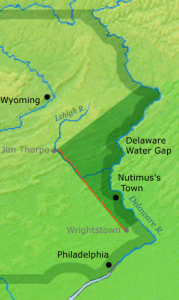

The Deceitful Walking Purchase

Pennsylvania strayed seriously from Penn’s vision of peaceful coexistence with the Lenapes in the 1730s, when his sons Thomas Penn (1702-75) and John Penn (1700-46), now the proprietors, plotted with their agent James Logan (1674-1751) to acquire lands in central and northern Bucks County. Logan had already made an illegal individual purchase in 1726 to build the Durham iron furnace. To facilitate what became known as the Walking Purchase, he located an unsigned draft deed dated 1686—not a signed document—that he claimed as proof that the Lenapes had sold all territory that could be walked in a day and a half north from the previous boundary at Wrightstown. On September 19, 1737, three young settlers ran, rather than walked, a route cleared in advance, covering much more territory than Lenape leaders expected. On the second day just one of the settlers finished the run, completing sixty-four miles in eighteen hours. Logan started the new boundary there, extending a diagonal line northeast to the Delaware River to maximize the “purchase” of more than one million acres.

The fraudulent Walking Purchase forced many Lenapes west to the Susquehanna and Ohio valleys in the 1740s and 1750s as the proprietors sold lands in northern Bucks County and the Lehigh Valley to speculators and immigrants. The Lenapes, called Delawares by the English, joined the Conestogas (Susquehannocks) and Indians from Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina who had migrated into the Susquehanna Valley. In the Ohio country, Delawares allied with Shawnees and Senecas. Though some Lenapes joined Moravian missions in eastern Pennsylvania in the 1740s, they too eventually relocated to the Ohio Valley with rising tensions and war between natives and European settlers.

The Seven Years’ War ended the tenuous peace in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware. In the mid-1750s, in response to incursions from Virginia, Pennsylvania, and the British government, many natives of the Susquehanna and Ohio valleys allied with French troops and colonists who claimed the region from Canada through the Ohio and Mississippi valleys to Louisiana. After French troops and their Indian allies overwhelmed the army of British General Edward Braddock (1695-1755) in July 1755, Delawares and Shawnees attacked European settlements from western Pennsylvania to northwestern New Jersey. The outbreak of war provoked a political crisis for pacifist Quaker legislators who had dominated the Pennsylvania assembly yet successfully avoided military actions that jeopardized their beliefs. In 1756, ten Quaker assemblymen resigned, thus relinquishing Friends’ control. The Pennsylvania government funded the war and unleashed violence against natives by offering scalp bounties. New Jersey required Lenapes to wear a red ribbon and carry identification. The New Jersey government also appointed five commissioners who instructed the natives to bring in a list of lands they claimed as unsold. When the Lenapes submitted their list in 1758, the commissioners noted that colonists had settled on much of the territory. The sachems accepted a three-thousand-acre reservation called Brotherton in southern Burlington County in return for all but a few parcels of land.

Boundaries and Indian Wars

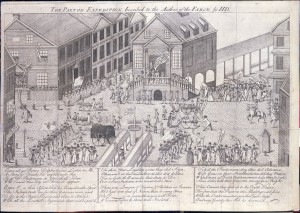

The Easton Treaty of 1758 brought short-lived peace to the region when the Delaware sachem Teedyuscung (1700?-1763), with support from Quaker leaders, obtained a pledge from the British to recognize Indian possession of the Ohio country after defeat of the French. Teedyuscung and the Quakers made it clear that the Walking Purchase had motivated Delawares to go to war. Peace proved illusory despite the Proclamation Line of 1763, by which the British government sought to create a boundary along the crest of the Appalachian Mountains between the colonies and Indian country. In 1763, spurred by continued white settlement and the nativist doctrine of the Delaware prophet Neolin, Indians attacked forts and colonists in the Great Lakes region, Ohio country, and Pennsylvania frontier in what became known as Pontiac’s War (1763-66). The largely Scots-Irish vigilante Paxton Boys of Lancaster County then killed neighboring Conestogas, allies of the Pennsylvania government since 1701, and marched to murder refugee Moravian Delawares in Philadelphia, but turned back after negotiating with Benjamin Franklin. The Paxton Boys reflected anger among Scots-Irish Presbyterians in western Pennsylvania who blamed Quakers for their support of Native Americans and the Assembly’s failure to provide adequate defense.

The end of Pontiac’s War brought only a temporary halt to hostilities between European settlers and Indians, as colonists continued to push west. Hatred exacerbated by more than a decade of war heightened boundaries between natives and colonists. Still, in New Jersey, Delaware, and parts of eastern Pennsylvania, Lenape and Nanticoke families continued to live in their homeland, often in the Pine Barrens and other marginal areas.

By 1765, the Delaware Valley was no longer Lenape country, a land without rigid boundaries and fences, but it remained a region integrated economically, socially, and culturally. The site of Philadelphia at the confluence of the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers provided an important nucleus of trade for southeastern Pennsylvania, West Jersey, and Delaware just as it had served the Lenapes and Dutch, Swedish, Finnish, and English settlers more than a century earlier. The English had drawn boundaries between the three colonies and then divided the provinces into counties and local governments. Legally and culturally many colonists created racial lines between whites, who could not be enslaved, and Africans and Indians who could be denied freedom and land. Beginning with the Lenapes, the region developed a culture that placed greater emphasis on peaceful resolution of conflict, religious freedom, and personal liberty than other North American colonies, even as economic development encouraged the growth of slavery and expropriation of native lands, leading to war. The Delaware Valley’s culture had a foundation as diverse and complicated as its people.

Jean R. Soderlund is Professor of History emeritus at Lehigh University. She is the author of articles and books on the history of the early Delaware Valley, including Quakers and Slavery: A Divided Spirit (1985) and Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society before William Penn (2015), for which she won the 2016 Philip S. Klein Book Prize from the Pennsylvania Historical Association.

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University