Center City Philadelphia

The Vine Street Expressway runs between the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers. Plans for its construction were delayed for decades due to the impact it would have on neighborhoods like Chinatown.

Market Street, originally called High Street, was Philadelphia's earliest commercial and civic corridor and home to some of the city's most important buildings including the city's first courthouse and City Hall.

Underground concourses in Center City Philadelphia played a crucial part in the construction of subway tunnels and then expanded into a network of pedestrian walkways, including connections to Suburban Station.

Philadelphia was a leader in urban renewal in the decades following World War II. The plan to revitalize Society Hill, for example, employed an innovative combination of smaller-scale spot demolition, modern infill construction, and historic preservation.

Visitors to Philadelphia's 'Tenderloin'' enjoyed the district’s many working-class entertainment options. In the early 1910s, Frank Dumont moved his famous minstrel show to Ninth and Arch Streets.

Philadelphia boasts the oldest and one of the largest urban park systems in the United States, comprising more than one hundred parks encompassing some ten thousand acres.

A long segment of Broad Street has been dubbed the 'Avenue of the Arts' since 1993, growing into a vibrant string of performing arts venues and residential buildings. The Academy of Music is in the 200 block of South Broad.

Philadelphia-area residents and visitors have required places for large assemblies since the colonial era. Today the Pennsylvania Convention Center downtown is the city's main site for conventions.

Since construction began in the early 1960s, the vision for Penn’s Landing on the Delaware River waterfront has evolved from a public space devoted to historic and museum facilities, to a locus for private development, to an arts and entertainment venue.

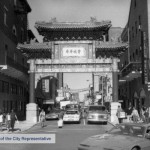

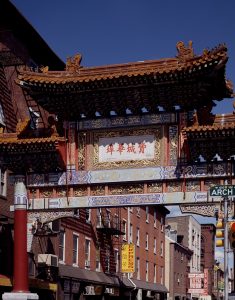

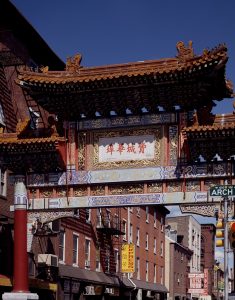

Settled by Chinese migrants in the 1870s, Philadelphia’s Chinatown grew over the course of the twentieth century from a small ethnic enclave on the outskirts of Skid Row to a vibrant family community in the heart of Center City. Threatened by urban renewal in the 1960s and 1970s, Chinatown residents marshaled the redevelopment process to rebuild and expand their community over the course of the late twentieth century. This legacy of activism continued to inform struggles against gentrification and for affordable housing, education, and community self-determination. While Chinese and other Asian immigrants dispersed throughout the greater Philadelphia area, Chinatown remained as a central touchstone for Asian life in the region.

From 1840 through 1880, a commercial district of cast iron buildings developed in Center City, helping to define the downtown of the emerging modern city, clustered from the Delaware waterfront to Twelfth Street between Arch and Pine Streets. The Smythe Stores building is now a residential building.

Society Hill has evolved from the mixed-use neighborhood of a colonial town, to a big city ward that contained slums, to the modern gentrified 'gold coast' marked with luxury living spaces and high-rise condominiums like the Society Hill Towers.

Lining Philadelphia’s straight, gridiron streets, the row house defines the vernacular architecture of the city and reflects the ambitions of the people who built and lived there.

Led by John Wanamaker, Philadelphia's Market Street department stores became the national model. Known as the "Big Six," these businesses were close to the city's rail terminals and subway stations.

Mother Bethel AME Church: Congregation and Community

Established in the Revolutionary era, Mother Bethel AME Church is recognized as the genesis of Black religious organizing spirit.

Although only officially titled in 2005, the Gayborhood has served a vital role in the social and political struggles of LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) peoples of Philadelphia since the 1940s.

The German Reformed Church played a role in developing the religious landscape of southeastern Pennsylvania.

Philadelphia enacted the first municipal law mandating fire escapes on all sorts of buildings and is associated with a design innovation: Philadelphia fire tower, as seen near Thirteenth and Walnut Streets.

Arthur Mervyn; or, Memoirs of the Year 1793

Philadelphia native Charles Brockden Brown's novel, Arthur Mervyn; or, Memoirs of the Year 1793, became one of the most influential works of American Gothic literature. The author's final resting place is the Arch Street Friends Burial Ground, Fourth and Arch Street.

Jonathan Demme's 1993 film 'Philadelphia' attempted to reform the public understanding of AIDS at a time of prejudice and hate. In the context of the film, the Mellon Bank Building housed the law firm of protagonist Andy Beckett.

The Philadelphia mayoralty has experienced a variety of changes and challenges since its inception in 1701. The Mayor's Office is located at City Hall.

Philadelphia became one of the nation's major manufacturers of silk in the early nineteenth century. The city's most well-known silk goods maker, Horstmann & Sons, was located at Fifth and Cherry Streets.

Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

Over eighteen years, from 1771 until his death, Benjamin Franklin composed his autobiography. His legacy is immortalized at the Benjamin Franklin Museum in Center City.

Slovak immigrants made important contributions to Philadelphia industries from iron and steel to leather and textiles. Many Slovak artisans did wirework for the city at factories such as this now-converted location on Race Street.

Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul

The Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul, established in 1846, is the largest Catholic Church in Pennsylvania and the mother church of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia

Philadelphia's encounter with Modern Greece dates from the Greek War of Independence in 1821, and thousands of Greek immigrants arrived in the region beginning at the turn of the twentieth century. St. George's Greek Orthodox Cathedral was dedicated in 1921.

The Independence Seaport Museum is home to an extensive collection of the Greater Delaware Valley's maritime history and two iconic vessels, the Becuna submarine and the USS Olympia.

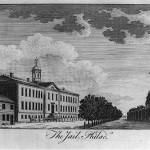

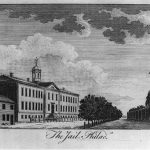

Philadelphia was at the center of the early prison reform movement, first introducing individual cells at Walnut Street Prison and later solitary confinement. The city's prisons later became notorious for conducting experiments on prisoners and a high rate of incarceration.

From its inception, zoning became a fraught subject. By empowering neighborhood groups and local politicians with power over land use in their communities, zoning brought such groups in Philadelphia and elsewhere into contest with developers, industrial concerns, and sometimes with other people who wanted to move into their neighborhoods. In 1962, Mayor James Tate signed a major overhaul to the zoning code at City Hall, the first revision to the code since 1933.

Free clinics known as dispensaries served the “working poor” from the eighteenth through the early twentieth centuries. The Philadelphia Dispensary for the Medical Relief of the Poor, considered the nation’s first, opened in 1786 and erected a new building on Fifth Street in 1801.

The late twentieth century proliferation of nuclear power plants and a partial meltdown at the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating station led to widespread protests. The PECO building in Philadelphia was a frequent target.

Anglican Church (Church of England)

Completed in 1753, Christ Church was a meeting place for Anglicans before the American War for Independence.

Philadelphia society's elite gathers annually for the Dancing Assemblies. The lavish ball has been held in a number of the city's most respected venues including the City Tavern and the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel.

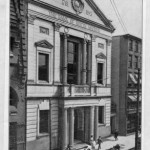

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s headquarters houses over six hundred thousand printed items and more than twenty-one million manuscript and graphic items, providing researchers with more than 350 years of historical sources.

Philadelphia helped define the toy industry in the United States with simple yet engaging toys that became beloved by generations. Schoenhut's Humpty Dumpty Circus featured a camel, which is now housed at the Philadelphia History Museum at Atwater Kent.

A predecessor for the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Musical Fund Society formed in 1820 to promote professional and amateur musical talent in Philadelphia. For many years, the society operated Musical Fund Hall, the center of Philadelphia's music scene.

Although initially focused on self-improvement, women’s clubs in the Philadelphia region, like the New Century Club, quickly extended their goals to include community activism.

Carrying artifacts and documents of American History, the Freedom Train left from Broad Street Station on a journey to unify the American people against the encroaching threat of communism.

Charter schools in the Philadelphia region began opening in the late 1990s. Among the operating charters in 2016-17 was the Independence Charter School at Sixteenth and Lombard Streets.

Armstrong Association of Philadelphia

The Armstrong Association of Philadelphia, an interracial organization that aided African Americans with job placement and adequate housing, operated a learning and social center at the Thomas Durham Public School.

Library Company of Philadelphia

Since its inception in 1727, the Library Company of Philadelphia has evolved from a member based lending library into a invaluable archival resource.

Founded in 1800 and located at Twenty-First and Race Streets, the Magdalen Society of Philadelphia was the first institution in the United States concerned with caring for and reforming “fallen women.”

The Whigs, the opposition party to Andrew Jackson and the Democrats during the antebellum era, gave Zachary Taylor their nomination for President at the Chinese Museum, located here in 1848.

Children’s Aid Society of Pennsylvania

Founded in 1882 to address social issues in Philadelphia, the Children's Aid Society of Pennsylvania merged in 2008 with the Philadelphia Society for Services to Children and formed Turning Points for Children.

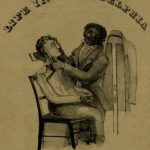

Mother Bethel church in Philadelphia is the oldest AME (African Methodist Episcopal) Church in the United States. Churches were staples for black communities and continue to hold places of leadership.

Clockmakers beginning in the colonial era have made clocks that have become Philadelphia landmarks, including the Thomas Stretch clock at Independence Hall.

Philadelphia has been home to prestigious classical music groups, venues, and schools like the Settlement Music School. Composers in Philadelphia also wrote the first classical pieces penned in the American colonies.

The telephone was first demonstrated at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition. Since then Philadelphia has been home to many telephone innovations and several telephone companies, including Bell Telephone, which built offices at 1827 Arch Street.

Known for portraiture, Cecilia Beaux studied and taught at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, located at Broad and Cherry Streets.

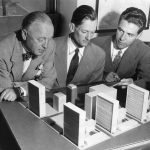

Published in 1967, the book Design of Cities by Edmund Bacon assessed urban development through the ages while highlighting redevelopment projects in postwar Philadelphia, including Penn Center at Sixteenth and Market, west of City Hall.

Literary Societies provided Philadelphia's elite with a place for intellectual and artistic discourse. Some, like the Acorn and Rittenhouse Clubs, remained active in the twenty-first century.

Philadelphia Maritime Exchange

The Philadelphia Maritime Exchange helped turn Philadelphia into a premier port in the U.S. Its legacy is preserved in the collections of the Independence Seaport Museum on Columbus Boulevard along the Delaware River.

The renowned Dream Garden, a glass mosaic designed by Maxfield Parrish with favrile glass by Tiffany Studios, has stood in the foyer of the Curtis Publishing Building since 1916.

From the minuets and waltzes of the city's early years to jazz, swing, and the tango, social dance has been an active part of the Philadelphia area's social scene. Dance schools pepper the region, including one on Rittenhouse Square.

Mexicans became the region’s second-largest immigrant group in the early twenty-first century, impacting the region's culture and economy. The Mexican Cultural Center of Philadelphia is in the Bourse Building, near Independence Hall.

Philadelphia was home to a succession of literary magazines that helped establish a national literary culture. Among them, Curtis Publishing on Walnut Street produced The Ladies Home Journal and The Saturday Evening Post.

Philadelphia was one of the first American cities with a branch of the fraternal society known as the Freemasons, whose ornate temple in Philadelphia is one of the most prominent in all of Freemasonry.

Philadelphia has been home to Catholic parishes since the colonial era. Despite declines in recent decades, the church maintains a strong presence. Old St. Joseph's on Willings Alley opened in 1733.

Philadelphia became an early leader in hotel development, introducing innovations in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The Bellevue-Stratford Hotel was widely considered to be the most extravagant hotel in the country.

Smoking and Smoking Regulations

Tobacco has been smoked in the Philadelphia area for social, medicinal, and religious uses since the precolonial era. N.W. Ayer & Son on Washington Square created ads for both R.J. Reynolds’ and Phillip Morris Companies.

“Oh, Dem Golden Slippers,” unofficial theme song of the Philadelphia Mummers Parade, was written by James Bland in 1879. Near the end of his life, Bland worked for Dumont Minstrel Theater at Ninth and Arch Streets.

Crowds (Colonial and Revolution Eras)

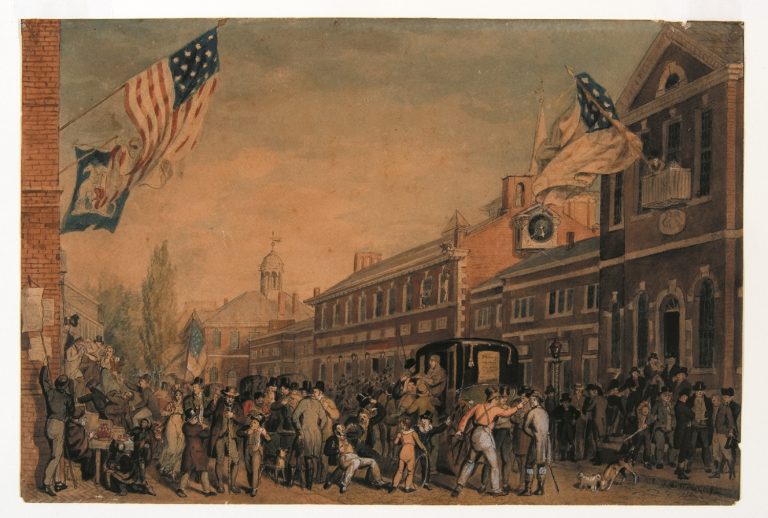

Ordinary people helped shape the political culture by engaging in public celebrations, civil disorder, and, occasionally, collective violence. Crowds in the State House yard, for instance, heard and cheered the Declaration of Independence.

Philadelphia helped give birth to the single tax movement, popularized by economist and Philadelphia native Henry George, whose birthplace is on South Tenth Street.

Works Progress Administration (WPA)

The WPA provided jobs for thousands of Philadelphians, but not enough to help everyone. WPA workers added a rail line to the Benjamin Franklin Bridge, the line that today carries PATCO trains between Philadelphia and Camden, New Jersey.

Television Shows (About Philadelphia)

The Philadelphia region has provided a backdrop for many television programs, including an early season of MTV's the Real World, whose cast lived in an old bank building at Third and Arch Streets.

General Trades Union Strike (1835)

The General Trades Union Strike of 1835 was the nation's first general strike, prompted by coal heavers working along the Schuylkill River and demanding a ten-hour day.

During the Greek War for Independence (1821-28), Philadelphians helped arouse public sentiment in favor of the Greeks and raised money and provisions to aid the cause. The Second Bank was modeled on the Parthenon of Athens.

The Spanish-American War had a significant influence on Philadelphia, and the USS Olympia, the flagship of the U.S. Asiatic Squadron, is permanently moored as Penn's Landing.

Since the early nineteenth century, a number of historical societies have called Philadelphia home, from small religious and local history groups to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Spurred by reports of deplorable conditions at the Walnut Street Jail, a nondenominational group of religiously motivated activists set out to reform Philadelphia's prisons. Their reforms soon spread to prisons around the world.

The arrival on July 21, 1877 of Philadelphia militiamen, deployed from their armory at 21st and Ranstead Streets, turned the relatively peaceful railroad strike in Pittsburgh into a scene of violence and disorder.

Rooted in a trade union coalition that formed near this location, the Working Men's Party organized the city's laboring class, gained seats in city government, and pressured the city and state to change laws that impacted poor and working-class citizens.

WHYY moved into television programming in 1957, broadcasting from studios at 1622 Chestnut Street—a renowned Art Deco building formerly home to WCAU.

TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia)

Local record label Philadelphia International Records scored a #1 hit when they records 'TSOP' -- The Sound of Philadelphia -- for the national television program Soul Train.

City Merchant (The); or, The Mysterious Failure

A fictional account of real events, The City Merchant by John Beauchamp Jones blames the tumultuous events of the antebellum period on abolitionists and unscrupulous real estate deals. The Second Bank of the United States is part of the plot.

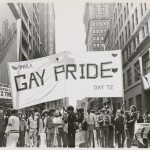

The annual Reminder Days demonstration at Independence Hall predated the Stonewall riots and stand among the first gay rights demonstrations in the United States.

From colonial militias to Cold War fallout shelters and nuclear bomb drills, Philadelphia's citizens have prepared for disaster throughout the city's history. Civil Defense remnants still show up, including fallout shelter signs at City Hall.

Contractor bosses dominated Philadelphia politics from the 1880s to the 1930s, enriching themselves and costing taxpayers millions annually. Building City Hall dragged on for thirty years.

Shoemaking was a large and influential occupation in early Philadelphia. In 1827, cordwainer William Heighton founded the Mechanics' Free Press and helped found the Mechanics’ Union of Trade Associations at Chestnut and Bank Streets.

Joseph Hopkinson lived on Spruce Street while he was drafting the lyrics to 'Hail, Columbia,' which for many years served as the unofficial national anthem.

Philadelphians organized trade unions and supported one of the most successful labor demonstrations in the antebellum period, the General Strike of 1835. Soon after the strike began, protesters filled the Merchants' Exchange on Walnut Street.

Based on plans by Paul Cret and Jacques Gréber, much of the Fairmount Parkway (renamed Benjamin Franklin Parkway) including the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Free Library, and Logan Circle, was completed or under construction by 1930.

The City Beautiful Movement had significant influence on Philadelphia, including Rittenhouse Square, redesigned in 1913 with diagonal walkways, fountains, tree plantings, and sculptures. 'Billy' is a public favorite at the southwest corner.

Philadelphians participated enthusiastically in trade with China after the Revolution, importing silks, tea, and porcelain into the city—often by illegally smuggling opium into China. The Philadelphia Seaport Museum is on Columbus Boulevard at Penn's Landing.

During the Vietnam War era, demonstrations were common at JFK Plaza near City Hall as well as symbolic sites such as the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall.

Philadelphia’s Fifth Ward, south of Chestnut near the Delaware River, became infamous in the late nineteenth century for election-day riots among Irish, Black people, and the police. In the twentieth century, the area was cleaned up and rebranded as Society Hill.

Police Department (Philadelphia)

The Philadelphia Police Department was created in 1854, and since 1962 has been headquartered in the Police Administration Building also known as 'The Roundhouse' on Race Street.

Philadelphia suffered many epidemics in its early years, and Pennsylvania Hospital on Spruce Street was in the forefront of battling them. Most were overcome by the early twentieth century, but some, like polio and HIV, posed new challenges.

An offshoot of the city's long jazz and African American vocal music traditions, rhythm and blues music saw Philadelphia musicians drawing crowds. A key figure was bandleader Louis Jordan, who played at the Earle Theatre at Eleventh and Market Streets.

The early 1950s conflict between North Korea and South Korea had a big impact on Greater Philadelphia, leading to a surge in shipbuilding employment and the deaths of hundreds of local servicemen.

Since the early nineteenth century, the Academy of Natural Sciences has sought to fulfill a dual mission of scientific discovery and the diffusion of knowledge.

Presidents of the United States (Connections to Region)

U.S. presidents have long visited Philadelphia to invoke the historic values of the country's founding documents. Independence Hall has been the backdrop for many such visits, beginning in 1833 with Andrew Jackson.

Veterans and Veterans’ Organizations

Military veterans began organizing during the waning days of the Revolutionary War and continued to form organizations such as the Philadelphia Veterans Advisory Commission, established in 1957 and located in City Hall.

309 S. Broad Street was home first to Cameo-Parkway, then Philadelphia International Records, both of which helped shape the Philadelphia soul sound. The building was demolished in 2015 to make way for condos.

Coffeehouses have been an integral part of the region's social fabric since the eighteenth century. The Old London near the Delaware River waterfront was Philadelphia’s leading coffeehouse in the 1760s, owned by printer William Bradford.

Public markets in Philadelphia belong to an ancient tradition of urban food provisioning. The Reading Terminal, which opened in 1892, opened a new era for urban food marketing and distribution.

From 1965 through 1969, activists marched for gay rights each July Fourth in front of Independence Hall on July fourth. A historical marker at Sixth and Chestnut Streets commemorates the demonstrations, which became known as Annual Reminders.

A nondenominational mutual aid society, the Free African Society was founded in 1787 by Richard Allen and Absalom Jones. Jones also led the the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, originally located at Fifth and Adelphi Streets (St. James Place).

American Philosophical Society

Established in 1743 by Benjamin Franklin and John Bartram to 'promote useful knowledge,' the American Philosophical Society brought renown to colonial scientists. It continues its intellectual pursuits on Fifth Street near Walnut.

Philadelphia was Quaker William Penn's 'holy experiment' in founding a colony of virtuous Quakers. The influence of the church can still be felt today, and the Arch Street Meeting House still stands.

Originally displayed in Philosophical Hall on Independence Square, this trompe l'oeil double portrait by Charles Willson Peale gained new attention after its display in the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the twentieth century.

Quaker City (The); Or, the Monks of Monk Hall

The Quaker City, a Gothic novel written in the 1840s by George Lippard, is set in part along the Delaware River waterfront, later developed as Penn's Landing.

The Franklin Institute, established in 1824, moved to its new home on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in 1934.

Written by S. Weir Mitchell, <i>The Red City</i> was set in 1790s Philadelphia, a place divided by the Federalists and Republicans and a place that served as a refuge for French emigres. The President's House served as the office and residence for President George Washington.

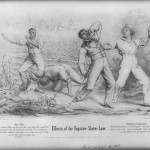

Because of its abolitionist posture, Pennsylvania became a haven for fugitive slaves from neighboring states. Slave catchers and abolitionists tangled, and some cases were decided by hearings in what came to be known as Independence Hall.

Founded in 1900, the Philadelphia Orchestra developed into an iconic organization for Philadelphia and cultural ambassador to the world. The orchestra's home is the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts.

The Philadelphia Award, founded in 1921 to annually honor a citizen for service that advances 'the best and largest interests of Philadelphia, was presented at the Academy of Music on Broad Street until 1950, when the ceremony moved to the Barclay Hotel.

The Friends Almshouse, operated by the Quakers in 1713, provided poor relief for Quakers. Over time, almshouses evolved from being run by voluntary associations to ones operated by government.

Naturalists and illustrators helped make Philadelphia a center for the study of insects—entomology—as early as the eighteenth century. The butterfly collection of Titian Peale today resides in the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University.

Bank of the United States (First)

Originally located in Carpenters' Hall, the First Bank of the United States relocated to 116 S. Third Street in 1797.

Bookstores have long been an important part of the economic and cultural fabric of Philadelphia. Leary’s Book Store, one of the city’s most popular places to buy books in the nineteenth century, opened a store at this Ninth Street location in 1877.

The Grand Federal Procession, a Philadelphia parade celebrating the ratification of the Constitution, began at South and Third Streets on July 4, 1788.

The 1976 Legionnaire's disease outbreak centered on the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, where the disease's victims had gathered for an annual American Legion convention.

Philadelphia was a center of disease and medical exploration during the colonial period, and Pennsylvania Hospital at Eighth and Pine Streets was one of the first hospitals in the colonies.

Grand jury cases provide a window into the social, political, and legal issues that have engaged the region. Criminal courts for Philadelphia hear cases at the Julia E. Kidd Criminal Justice Center.

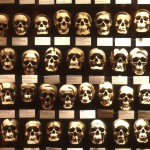

College of Physicians of Philadelphia

The College of Physicians of Philadelphia was founded in 1787 “to advance the science of medicine and to thereby lessen human misery.” It created professional standards and provided for the exchange of medical knowledge, while also establishing a renowned medical library and medical museum.

U.S. vegetarianism got its start in Philadelphia—Ben Franklin practiced it for a time. In the twenty-first century, the restaurant Vedge on Locust Street brought cutting edge vegan fare to Philadelphia.

As political, economic, and cultural capital of the early U.S., Philadelphia became a center for producing political cartoons and humorous caricatures, starting with Benjamin Franklin's widely reprinted 'Join, or Die' cartoon.

Innovative dentists in Philadelphia helped to shape dental care, procedures, and tools. The S.S. White firm, with a factory located here in the 1880s, became a premier manufacturer of dental tools.

Once a religious holiday and a political parade, Saint Patrick’s Day transformed over two centuries into a largely secular celebration reflecting the changing culture of Philadelphia’s Irish population and of the city at large.

Better Philadelphia Exhibition (1947)

The Better Philadelphia Exhibition held in 1947 at Gimbels department store in Center City showcased new ideas for revitalizing Philadelphia after decades of depression and war.

In 1965, discriminatory treatment at a Dewey's restaurant on South Seventeenth Street spurred the first such protest by the LGBT community. Faced with days of protest, the restaurant changed its policy.

During the Civil War, a group of pro-Union Republicans founded the Union League. Since then, it has transformed into the city's premier social club.

Board of Health (Philadelphia)

The Board of Health, located here, is a board the Philadelphia Department of Public Health composed of the Health Commissioner, who serves as President, and seven mayoral appointees.

For three years in the 1790s, Susanna Rowson performed and wrote plays in Philadelphia. The New Theatre on Chestnut Street was her stage.

Dozens of co-working spaces opened (and some failed) in the early decades of the twenty-first century in Greater Philadelphia, including the pioneering Indy Hall on North Third, offering shared work space designed to foster a collaborative atmosphere

Philadelphia has a distinguished history as a center of American painting. The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, founded in 1805, continues to train artists at its location on Broad Street.

Charles Willson Peale's Philadelphia Museum, with galleries inside Independence Hall, sought to cultivate an educated citizenry in the new nation.

Liberia; Or, Mr. Peyton’s Experiments

Liberia; Or, Mr. Peyton's Experiments, by Sarah Josepha Hale, advocated colonizing free African Americans in Liberia. The Pennsylvania Colonization Society once occupied an office on a street opposite of Washington Square.

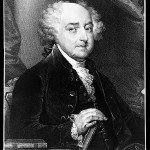

Passed while Congress met in Philadelphia, the Alien and Sedition Acts created a political backlash during the presidency of John Adams.

The Friends Select School has helped make education accessible to every student, continuing a legacy that started with the first Quaker 'select school' in 1689.

After the work of Independence, the Second Continental Congress worked on drafting the Articles of Confederation, the first Constitution of the United States, at this location.

The Merchants' Exchange was an early home of the Philadelphia Board of Trade, which promoted economic development.

As the chief medical city in the United States during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Philadelphia also became the leading center of anatomical education. The Mütter Museum offers evidence of that, including an vast collection of skeletons.

Vigilance Committees (sometimes called Vigilant Committees) formed to protect fugitives and potential kidnap victims. Robert Purvis was one of Philadelphia's most prominent abolitionists. His home at Ninth and Lombard Streets had a secret area for hiding slaves.

The central event in the novel, 'The Garies and Their Friends,' is a graphically-rendered race riot, evoking the historical riots of 1834, 1838, 1842, and 1849. One of these riots, the Lombard Street Riot, has a historical marker located at Sixth and Lombard Streets.

The nineteenth-century phrase 'puzzle a Philadelphia lawyer' means to pose a difficult problem only an expert could solve. Today, Philadelphia lawyers can be seen at work in the Criminal Justice Center on Filbert Street.

The Crosstown Expressway, a proposed highway on the south edge of Center City, spurred prolonged controversy in the 1960s and 1970s as redevelopment schemes met with neighborhood resistance. Planners wanted it to join Interstate 95 near South and Second Streets. It was never built.

Revolutionary Crisis (American Revolution)

On the night of September 16, 1765, a large mob gathered at the State House to target individuals associated with the Stamp Act, including Ben Franklin.

The former location of the Dock Street Market, established in 1850, was home to numerous street vendors until its demolition in the 1950s.

The fifty-eight-story Comcast Center became the city's tallest building as it was topped out in 2007, but was eclipsed in 2016 by a second Comcast office tower at Eighteenth and Arch Streets.

Thanksgiving Day traditions evolved over time while retaining themes of early thanks-giving feasts. Philadelphia, home to the first Thanksgiving Day Parade, contributed to many traditions as they came to be practiced across the nation. In Philadelphia, the parade goes up Franklin Parkway to the Art Museum.

Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts

The Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts was designed as the centerpiece of the Avenue of the Arts, a rebranded stretch of Broad Street devoted to performing arts venues.

Although the federal government under the U.S. Constitution went into operation in New York, the capital moved to Philadelphia in 1790. George Washington lived in the President's House, as did John Adams when he succeeded Washington.

The original office of the Bank of North America was established at 309 Chestnut Street in 1781. In the beginning, the bank's offices were located in the home of the bank's first cashier, at the same address.

Book Publishing and Publishers

Book publishing flourished in Philadelphia in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Beginning with Benjamin Franklin, the city eventually hosted many competing publishing firms.

Godey’s Lady’s Book was the first successful women’s magazine and most widely circulated magazine in the antebellum United States, published on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia.

The novel 'Sheppard Lee' became famous in its day for its literary style and social commentary as its namesake character's soul migrated into the bodies of recently deceased acquaintances. Author Robert Montgomery Bird lived at 247 S. Tenth Street.

The first men's club in Philadelphia to offer billiards to its members appears to have been the Philadelphia Club, which added a billiards room to its new facility at Thirteenth and Walnut Streets in 1849.

During Prohibition, Philadelphia earned a reputation rivaling Chicago, Detroit, and New York City as a liquor-saturated municipality. Near Thirteenth and Locust Streets was The 21 Club, one of Max “Boo Boo” Hoff’s speakeasies.

The Saturday Evening Post’s circulation grew from two thousand to over three million copies an issue. This growth allowed the Curtis Publishing Company in 1910 to build a grand headquarters at the corner of Sixth and Walnut Streets near Independence Hall.

The public Mass held by Pope John Paul II on Logan Circle on October 3, 1979, drew more than a million people, by police estimates, stretching on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway from City Hall to the Art Museum and beyond.

United States Mint (Philadelphia)

Coins have been minted in Philadelphia as long as the federal government has produced legal tender coins. Since 1969, the mint has been located on the edge of Independence Mall, its fourth location in the city.

In 1851, an attempt to recapture escaped slaves in Christiana, Pennsylvania, turned into a riot in which one man was killed. The trial of one of the participants at the Old State House (Independence Hall) reflected growing abolitionist sentiment.

For nearly a hundred years from 1693 to 1781, Tun Tavern served residents and visitors of Philadelphia near the Delaware River waterfront with food, spirits, and sociability.

During Prohibition, Philadelphia earned a reputation rivaling Chicago, Detroit, and New York City as a liquor-saturated municipality. Near 13th and Locust Streets was The 21 Club, one of Max “Boo Boo” Hoff’s speakeasies.

The novel <i>Modern Chivalry</i> was published in installments from 1792 to 1815, wryly documenting life in the new republic. One episode targets pretensions at the American Philosophical Society.

Tension over abolition led to a number of riots, one of the most notable being the 1838 destruction of Pennsylvania Hall, a meeting place for antislavery groups on Sixth Street about two blocks north of Independence Hall.

Philadelphia Gas Works, one of the largest public utilities in the nation, has served Philadelphia residents since 1835. PGW's first plant was on the Schuylkill River between Market and Filbert streets.

The National Park Service uses parks and sites to preserve historical, cultural, and natural resources for future access and education. The Independence National Historical Park contains over thirty sites covering centuries of Philadelphia’s history.

The American Philosophical Society, located here in Philosophical Hall, received specimens from Lewis and Clark's expedition to the West.

Written by Thomas Paine and published by Robert Bell's print shop at this location on January 10, 1776, the pamphlet Common Sense helped rally support for independence.

Native and Colonial Go-Betweens

In the colonial era, as conflict between the Europeans and displaced Native American tribes rose, go-betweens helped soothe tensions. Native Americans and Europeans met near Second and Market Streets in 1728 in response to tension on the western frontier.

Masterpieces of copperplate engraving created by William Russell Birch captured images of the city during its decade as the nation's capital.

When Philadelphia's shirtwaist workers went on strike in December 1910, Philadelphia's largest shirtwaist manufacturer, M. Haber, operated at 225 S. Fifth Street.

While it was the U.S. capital, Philadelphia was site of the first convictions of American citizens of treason—two of ten men tried for participation in the Whiskey Rebellion, which began in 1791 as a protest against an excise tax levied on domestic whiskey. The trial was at Old City Hall in 1795.

Constitutional Convention of 1787

The Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787, at Independence Hall (then known as the Pennsylvania State House) to draft the United States Constitution.

'Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens'

Musical Fund Hall is where a convention altered the Pa. Constitution to disallow voting by black residents, a move that inspired the essay 'Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens, Threatened with Disfranchisement, to the People of Philadelphia,' which argued against ratification.

The Philadelphia Stock Exchange helped the fledgling nation raise funds to develop infrastructure for a growing industrial base and new commercial banks and insurance companies.

As the national capital from 1790 to 1800, Philadelphia was the seat of the federal government for a short but crucial time in the new nation’s history.

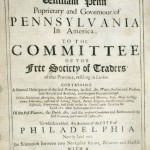

The Free Society of Traders, a joint-stock company founded by a small group of English Quakers in 1681, was organized with the intention of directing and dominating the economic life of colonial Pennsylvania.

The Athenaeum of Philadelphia, a not-for-profit, member-supported library, was founded in 1814 “to disseminate useful knowledge.” Over the twentieth century, the Athenaeum has grown to support more diverse programming and records.

By supplying provisions to British military troops or providing safety in the form of row houses on Pine Street for 450 Acadians fleeing Nova Scotia, Philadelphia played a significant role in the Seven Years' War.

Colonization Movement (Africa)

The African colonization movement was a nineteenth century attempt to resettle free Black people from North America to countries like Liberia. The Pennsylvania Colonization Society had offices here, and raised funds for the costs of traveling to Liberia.

The Gallery at Market East attempted to revitalize Philadelphia’s deteriorating retail space by luring suburban shoppers to Market Street. The Gallery offered shoppers easy access to the city's public transportation and an indoor shopping space.

Before the Fair Housing Act of 1968, Philadelphia and its suburbs grappled with policies that severely limited African American housing options. Agencies like the Human Relations Commission and the Fair Housing Commission, located at 601 Walnut Street, assist the public against discriminatory practices.

Indian Rights Organizations (Nineteenth Century)

In Philadelphia, an incubator for reform movements, women and religious organizations led the way in considering the plight of Native Americans.

The U. S. Congress met in Philadelphia for ten years, testing the endurance of the Constitution and set the groundwork for future political practice.

Immigration and Migration (Colonial Era)

Diverse peoples immigrating or migrating from Europe, Africa, and other American colonies before the Revolutionary War turned Philadelphia into colonial America's largest city.

Philadelphia's cemeteries have matured over time from small, private grave sites and potters fields scattered throughout the city to expansive rural cemeteries and memorial parks that honor the lives of the past.

National Negro Convention Movement

National Negro Conventions held from 1830 to 1864 brought together African Americans to debate and adopt strategies to elevate the status of free Blacks in the North and promote the abolition of slavery.

On October 4, 1779, the house of James Wilson went from being the residence of a wealthy Philadelphia merchant to becoming a stronghold against a rowdy group of militiamen taking action against war profiteers.

Washington Square in the early twentieth-century served as the nexus for three of Philadelphia's most prominent medical publishers. Medical students throughout the country read textbooks and manuals produced by these medical publishers.

Dubbed the “Philadelphia Plan,” the program requiring federal contractors to practice nondiscrimination in hiring tested the liberal coalition formed in the aftermath of the New Deal in Philadelphia and nationally.

The educational opportunities in Philadelphia have expanded greatly for students throughout the twentieth century, but the result has been a greater inequality between public and private schools.

People of African descent have migrated to Philadelphia since the seventeenth century. Although African Americans faced discrimination, disfranchisement, and periodic race riots in the 1800s, the community attracted tens of thousands of people during World War I's Great Migration.

The settlement house movement spread to Philadelphia in the 1890s as a large influx of needy immigrants and unsanitary conditions in the city attracted the attention of middle-class, college-educated reformers.

The Knights of Labor, the first national industrial union in the United States, was founded in Philadelphia on December 9, 1869. By mid-1886 nearly one million laborers called themselves Knights.

Public bathing became a civil and social imperative in the Philadelphia region and elsewhere in the United States during the second half of the nineteenth century.

During the decade the federal capital was in Philadelphia, United States policy toward St. Domingue changed substantially. Important policy decisions emanated from the presidential residence.

An estimated two million visitors attended Bicentennial celebrations, but the summer of ’76 ultimately failed to fulfill the dreams of the city and its planners. Completed projects included a new visitor center for Independence National Historical Park.

For most of the decades since the United States’ immigration restriction acts of the 1920s, Philadelphia was not a major destination for immigrants, but at the end of the twentieth century the region re-emerged as a significant gateway.

In the U.S., Philadelphians initiated the transition from imports and small-scale preparation to large-scale manufacturing of paint materials. Samuel Wetherill Jr. erected a factory in 1809 to produce lead pigments.

Printing and Publishing (to 1950)

As Philadelphia evolved into America’s largest port city, the number of printer-publishers operating within it grew. Philadelphia’s colonial printers generally located their shops close to highly trafficked areas.

Public transportation – consisting of vehicles that operate on fixed routes used by the public – began in the region in 1688 with a ferry between Philadelphia and what is now Camden, New Jersey.

Roman Catholic Education (Elementary and Secondary)

For more than three centuries Parochial schools in the Philadelphia region have responded to the changing characteristics of the region’s Catholic population.

Delaware Avenue (Columbus Boulevard)

Delaware Avenue played a significant role in the development of the city's maritime activity.

Philadelphia’s subway and elevated network, the result of more than eight decades of planning and construction, consists of four lines that connect with other transit options to serve much of the region.

American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU)

The American Civil Liberties Union, a national legal organization, organized in Philadelphia in 1951.

Sounds of the City: The Colonial Era

At the intersection of Second and Market Streets, a center of early Philadelphia’s civic life, the soundscape quickly began to diverge from that of the countryside.

The Delaware River Port Authority was created nearly 100 years ago as a bi-state commission for the purpose of building a single toll bridge. A 1992 amendment gave the DRPA two new mandates–port unification and economic development-- both of which proved to be difficult to implement.

Political Parties (Origins, 1790s)

Long considered the “cradle of liberty” in America, Philadelphia was also the “cradle of political parties” that emerged in American politics during the 1790s.

In 1899, the University of Pennsylvania published The Philadelphia Negro. The report about Philadelphia's 7th Ward became a distinctive landmark in the annals of sociological study and social advocacy.

Constructed over a 30-year period at a cost approaching $25 million, Philadelphia City Hall stands as a monument both to the city’s grand ambitions and to the extravagance of its political culture.

Ladies Association of Philadelphia

In 1780, Esther De Berdt Reed penned a broadside titled “Sentiments of an American Woman” to rouse women to participate in the Revolutionary cause.

Early Philadelphia, an Atlantic trading hub, became both a focal point for the slave trade and a community of enslaved Africans. The London Coffee House was sometimes a location for slave trading.

Few regions in the United States can claim an abolitionist heritage as rich as Philadelphia. The Pennsylvania Abolition Society was founded in 1775 at the Rising Sun Tavern in Philadelphia.

As a port with longstanding commercial, cultural, and political connections with Spanish America, Philadelphia played a significant role in the era of Spanish-American revolutions and became a center for Hispanic studies.

The French Revolution of 1789 prompted many citizens to flee to the U.S. Most settled along the Delaware River in the Mulberry district of Philadelphia (an area between modern day Market Street, Arch Street, Second Street, and Columbus Boulevard).

Richard R. Wright Sr. founded Citizens and Southern Bank and Trust Company, as well as the National Freedom Day commemoration, celebrated February 1.

In Philadelphia, the site of the Constitutional Convention, commemoration of the document’s major anniversaries also has been complex and has reflected how regard for the Constitution and its connections to the city have evolved over time.

Representatives of twelve colonies assembled in Philadelphia in September 1774 at Carpenter's Hall in the First Continental Congress.

The Second Continental Congress worked through deep political divisions to create the Declaration of Independence, which was read to the public in Independence Square on July 8, 1776.

Philadelphia and Its People in Maps: The 1790s

Philadelphia was the premier urban city in North America during the Early National era. Using GIS technology, maps visualize the city between 1790 and 1800, when it was the capital of the United States.

Nestled between Second Street and the Delaware River, thirty-two Federal and Georgian residences stand as reminders of the early days of Philadelphia.

Doctors in Philadelphia diagnosed the first local case of what would later become known as AIDS 1981.The Mazzoni Center formed the Philadelphia AIDS Task Force to provide social services to those affected.

Philadelphia's Civil War sanitary fairs represented the spirit of patriotic volunteerism that pervaded the city during the Civil War. These grassroots efforts climaxed at the Great Central Fair of 1864 in Logan Square.

Independence National Historical Park

Independence National Historical Park preserves and provides access to Independence Hall, the Liberty Bell, and other American Revolution and early American history sites.

Originally the Pennsylvania State House, this landmark is associated with the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and is now a treasured shrine, tourist attraction, and World Heritage Site.

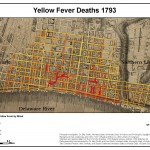

Yellow Fever hit Philadelphia with a vengeance in 1793. Beginning from a cluster of infections near the Delaware waterfront, the fever spread rapidly through the summer and autumn, fueling panic throughout the city.

For more than a century, the Liberty Bell has captured Americans’ affections and become a stand-in for the nation’s vaunted values: independence, freedom, unalienable rights, and equality.

The history of barbering in Philadelphia reflects trends in the region and nation, with barbering dominated by marginalized groups. Joseph Cassey, a free African American, found success in early nineteenth-century Philadelphia with his white-only barbershop.

Philadelphia's home-heating fuels changed over time, first wood, then coal, then oil and natural gas. When oil prices rose in the 1970s, the big migration to natural gas began. Headquarters for the electrical utility PECO is on Market Street.

Herpetology (Study of Amphibians and Reptiles)

Amphibians and reptiles fostered rich scientific discussions among early Philadelphia naturalists, including William Bartram and Charles Willson Peale, and the Academy of Natural Sciences published research on the subject.

Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) Strike

After the Philadelphia Transportation Company strikes of 1944, the company was bought and taken over by SEPTA, which today has a museum at 1234 Market Street.

Monument to Six Million Jewish Martyrs

The monument by Nathan Rapoport, dedicated in 1964, was the first public monument in North America to memorialize victims of the Holocaust.

African American Museum in Philadelphia

The African American Museum in Philadelphia (AAMP) was the first major museum of Black history and culture established by an American city.

Philadelphia has been a key center in popular music since the late eighteenth century. Philadelphia International Records, known for "the Sound of Philadelphia," was headquartered at 309 S. Broad Street.

Christ Church was the site for discussions about the foundation of a new American church, separate from the Church of England.

Telegraphy transformed communication in the nineteenth century and bridged distances between Philadelphia and cities across the globe. The Western Union Telegraph Building, later adapted into condominiums, recalls this significant era in communication history.

From the 1880s through 2017, postal services operated at Ninth and Chestnut Streets in Center City Philadelphia.

Roman Catholic Church and Catholics

Philadelphia’s first Catholic Mass was heard in 1708. The Roman Catholic Church grew over the centuries to become the single largest denomination in the Philadelphia region, and Catholics became integral to civic life and the ongoing struggle for full religious freedom. Constructed in 1788, Holy Trinity Church is located at the northwest corner of 6th and Spruce Street in Philadelphia. It opened as the first “national parish” in the United States built for German-speaking Catholics.

The Morans, a multi-generational family of American artists, lived and worked in Philadelphia during the second half of the nineteenth century. Many exhibited their work at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

Essay

Forming a core of civic, commercial, and residential life since Philadelphia’s seventeenth-century founding, Center City has been a continually evolving experiment in urban living and management. The roughly rectangular area of about 2.3 square miles between the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, from Vine Street to South Street, occupies the territory of the original 1682 city plan for Philadelphia. Once a forested expanse with hills, ponds, and streams, the land between the rivers transformed over time into a populated grid where residential and commercial interests jostled, shifted, and spread from east to west to fill in the footprint of “the city proper.” Rivers, roads, and later railroads, public transit, and highways linked the city with the wider region, making the urban core a hub for people, culture, and commerce—but also making it possible for residents and businesses to move to outlying neighborhoods and suburbs. In the twentieth century, new generations of city planners mobilized to combat the effects of suburbanization and revitalize Center City as a place where residents and visitors could live, work, and play.

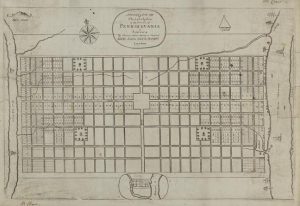

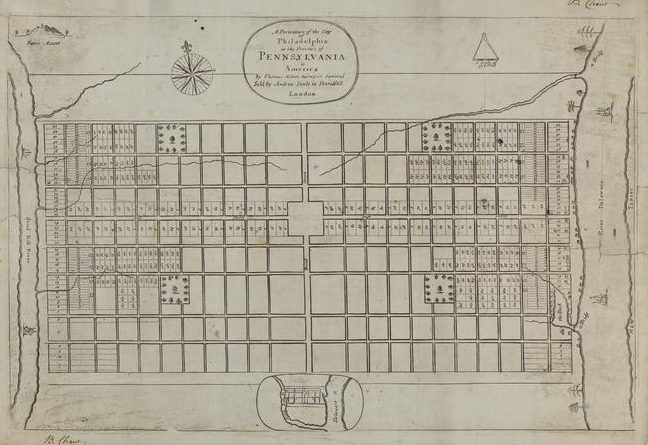

Surveyor Thomas Holme (1624-95) and founder William Penn (1644-1718) conceived the idea for a gridded city punctuated by garden squares in the 1680s. They drew inspiration from baroque town planning, post-Great London fire (1666) concerns for city health, desires to compensate initial investors in Pennsylvania with land, and personal preferences of Penn and early interest groups such as the Free Society of Traders. The plan drawn by Holme intended settlement to occur on both the Schuylkill and Delaware waterfronts and along the main streets of High (later Market) and Broad. After the first printing of the plan in 1683, the river-to-river grid appeared prominently on maps of Pennsylvania, but creating a city in the image of Penn and Holme’s plan required nearly two centuries of clearing trees, leveling land, extending streets, and building upon the grid.

Early settlement focused on the Delaware waterfront, which became the main site of commercial and residential building and growth during the colonial era. While property at the city plan’s western edge, on the Schuylkill, remained relatively open with scattered farms and industrial workshops, the Delaware riverfront grew with wharves, warehouses, churches, taverns, and houses. Settlement hugged the Delaware shore in a semi-crescent shape, most densely along High Street and thinning to the north and south. More and more residents clustered into the area by subdividing lots. Residences of the most prosperous Philadelphians faced the main streets while smaller houses on back alleys and courts filled with laborers and the poor. Instead of civic buildings on a center square, as Penn and Holme had planned, by the 1720s a town hall and Quaker meetinghouse anchored the city at Second and High Streets. Construction of the Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall) in the 1730s pulled the city westward to around Fifth Street, but as late as the 1790s, Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) received advice to rent quarters east of Seventh Street because “so few houses” stood farther west.

Port of Commerce and Entry

The port on the Delaware, ferries from New Jersey, and roads radiating outward into Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland enabled people and goods to move in and out of the compact city. Throughout the colonial era English, Irish, Scots-Irish, Welsh, German, and free and enslaved people of African heritage came through the port of Philadelphia to build and settle the city and surrounding region, which had been occupied earlier by Native American camps and Swedish settlements. From nearby hinterlands and across the Delaware River from New Jersey, agricultural products came to the High Street market and shipped out to other colonies and the world. The presence of the market, which extended to the west as the city grew, gave High Street of the original city plan a new name: Market Street (informally at first, made official in 1858).

The settled area of the city extended to Seventh Street by 1790, and by 1800 the forest had been cleared from river to river. In the decades following the American Revolution, as property values closest to commercial High Street increased, the settled area of Philadelphia became more segregated by economic status. The laboring class and the poor migrated in greater concentrations to low-rent districts at the southern and northern fringe, including a notoriously bawdy area known as “Helltown” north of Arch Street between Third Street and the Delaware River. Beginning in the 1790s and continuing into the early nineteenth century, a significant free African American neighborhood grew at Sixth and Lombard Streets, around Mother Bethel AME Church. African Americans also clustered in the area north of Arch Street and west of Fourth. A German neighborhood formed on the city’s northern border, and French immigrants who arrived during the French and Haitian revolutions opened businesses in the vicinity of Second and Walnut.

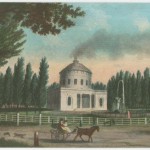

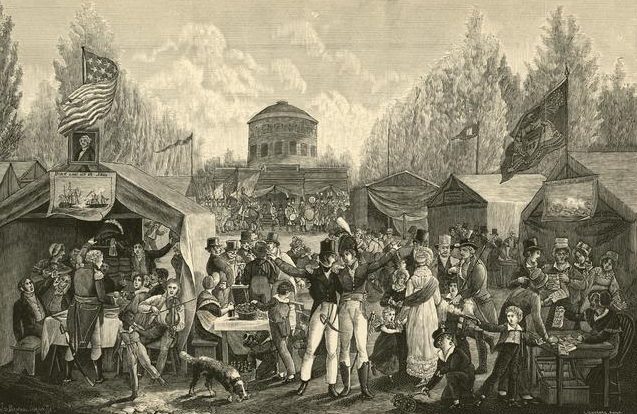

Philadelphians of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century made choices that imposed order and shaped the look and feel of the city proper for centuries to come. In 1795, city officials banned wood-frame buildings from inside the city limits, which assured that the fine rows of new homes built in the early decades of the nineteenth century would be made of red brick, often with marble-front raised basements and steps. The city government also looked back to the original city plan to guide improvements of the neglected public squares. Between 1801 and 1829 the center square, which Penn and Holme had intended for public buildings, became home to a neoclassical pump house that architect Benjamin Latrobe (1764-1820) designed to supply water to the city via a gravity-fed system from the Schuylkill. In 1825 the City Councils gave the squares new names that imprinted history in the landscape: Washington (for the southeast square), Franklin (northeast), Rittenhouse (southwest), Logan (northwest), and Penn (in the center). Washington and Franklin squares transformed during the 1820s and 1830s from neglected plots and sometime burial grounds into landscaped parks. Rittenhouse and Logan squares similarly improved during the 1840s and 1850s, as the population spread west. Rittenhouse Square became an especially prime address as lands west of Broad Street began to fill with row houses, new houses of worship, schools, and businesses during the 1850s and 1860s.

Expansion on the Waterfront and Inland

While residents and businesses planted new structures across the width of the grid, earlier settled blocks churned with changing purposes and redevelopment. The Merchants Exchange completed in 1834 at Third and Walnut Streets signaled the continuing importance of maritime commerce, as did the 1830s rebuilding of a warehouse district on Front Street north of Market Street and the creation of the waterfront Delaware Avenue, funded by a bequest of merchant Stephen Girard (1750-1831). However, businesses also moved inland from the waterfront and formed specialized clusters for banking, insurance, and publishing. In the oldest sections of the city proper, many colonial-era homes survived but deteriorated into subdivided multiple-family dwellings or industrial workshops. Homes associated with the nation’s founders gave way to commercial buildings on High Street, and factories replaced brick houses on Arch and Cherry Streets. Philadelphians built over cemeteries and turned streams into underground sewers.

The relationship of the city proper with outlying areas changed fundamentally from the 1830s through the 1850s, first with the expansion of public transportation networks and then with the Consolidation Act of 1854. Railroads, omnibuses, and horse-drawn streetcars allowed increasing numbers of Philadelphians to move beyond the boundaries of the original “walking city.” The Consolidation Act extended the city’s boundaries to encompass all of Philadelphia County, but in doing so it reduced the old city proper into a nameless section of a larger whole. “Old city proper” lingered as a name for the central city, remaining in use as late as the 1920s. However, by the late nineteenth and early centuries “center city” (or “centre city”) appeared frequently in newspaper advertisements for real estate and employment, suggesting a widespread understanding of the phrase as a designation for Philadelphia’s downtown. During the 1920s and 1930s, Center City (sometimes capitalized and sometimes not) became more common as a place name in advertising, in the names of buildings, and in city government communication. Thereafter, embraced by city planners as well as organizations such as the Center City Residents Association (formed in 1947), Center City dominated as the name for the old city proper.

Following consolidation, Philadelphians made another pivotal decision for the future shape and functions of the central city when they selected Penn (or Center) Square, the site Penn and Holme had intended for public buildings, as the location for a new City Hall. The site at Broad and Market Streets, determined by referendum in 1870 after years of debate, followed the westward trend of the city away from the traditional home of municipal government on Independence Square. By the time voters chose Penn Square over Washington Square, substantial development had occurred on Broad Street, including construction of the Academy of Music (opened in 1857) and fine hotels on South Broad and development of business and industry to the north. Anticipation of the new City Hall, which took form between 1871 and 1901, spurred additional nearby development. The Pennsylvania Railroad and Reading Railroad opened massive new stations on Market Street flanking Penn Square (Broad Street Station, built 1880-82 and expanded 1892-94 at Fifteenth Street, and the Reading Terminal, built 1891-93 at Twelfth Street). Adding to Broad Street’s status as a cultural corridor, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts moved to its new building designed by Frank Furness (1839-1912) in 1876. The same year, as Philadelphia celebrated the nation’s centennial, John Wanamaker (1838-1922) opened his “Grand Depot” store in the former Pennsylvania Railroad Freight Depot at Thirteenth and Market Street, heralding an era when large department stores drew crowds of shoppers from the city and surrounding areas to an increasingly bustling and diverse downtown.

Immigrant Settlement in Older Areas

Older blocks continued to lose their cachet but served as points of entry for immigrants and other new arrivals to Philadelphia. Beginning in the 1870s, a Chinatown began to form in the 900 block of Race Street as Chinese merchants and laundrymen migrated to Philadelphia from the West Coast. With few options, the Chinese created their community in the midst of a vice district known as the Tenderloin, north of Race Street between Sixth and Thirteenth Streets. In the remnants of the colonial city near the Delaware River, refugees from pogroms in Russia created a Jewish Quarter beginning in the 1880s. African Americans migrating from the South to escape repressive Jim Crow conditions extended the historically Black neighborhood around Mother Bethel AME Church westward toward Broad Street and beyond.

In the northwest quadrant of Center City, meanwhile, the new City Hall helped to fuel imagination of a grand new boulevard extending northwest to link the center of the city with Fairmount Park. Plans formed slowly but came to fruition with the opening of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in 1918. The civic improvement gave Philadelphia an expansive new avenue in the style of Paris and spurred development of a new cultural district around Logan Square (which became a traffic circle). In the process, the city demolished 1,300 residential and industrial properties but spared the Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul, which had faced Logan Square since 1846.

Although the urban core remained in part residential, by the early the twentieth century commerce and culture firmly dominated the landscape and the skyline. The central city reached new heights not only with the 548-foot tower of City Hall but also with the advent of skyscrapers, starting with the Land Title Building at Broad and Chestnut Streets (fifteen stories built 1897-98; twenty-two story addition built 1902). The combination of railroad stations, cultural institutions, department stores, and other businesses anchored Center City as a hub for commercial and cultural life, including conventions that filled Broad Street hotels. At the same time, a greater variety of residents gained the option of commuting from outlying areas on electrified streetcars (introduced in the 1890s), the Market-Frankford Subway-Elevated Line (built 1903-8, extended to Frankford in 1922), and the Broad Street Subway (1928-32). Motor vehicles added flexibility of travel and the option of driving to New Jersey over Philadelphia’s first bridge over the Delaware River, the Delaware River Bridge (opened in 1926 and renamed the Benjamin Franklin Bridge in 1955).

Restructuring in the Twentieth Century

As the region became more suburban from the late nineteenth into the twentieth century, Center City felt the impact. By the 1950s and 1960s, urban reformers focused their attention on areas of poverty and “blight” along the Delaware waterfront and in nearby neighborhoods. Pointing to areas that had “changed over the years from aesthetic assets to eyesores,” the Philadelphia Planning Commission led by Edmund Bacon (1910-2005), the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority (established 1945), and the Olde Philadelphia Development Corporation (1956) spearheaded massive restructuring plans for Center City that involved redeveloping areas perceived as slums and adding infrastructure. Catering to car culture, highways created new boundaries and connections for Center City. Construction of I-95 along the Delaware waterfront in the 1960s linked Philadelphia to the Northeast Corridor but largely cut off the city from its formerly bustling harbor. On the other side of town, the Schuylkill Expressway reached completion in 1958. Planners also sought to improve movement of automobile traffic across the city with new expressways along the northern and southern boundaries of the old city proper. They succeeded in implementing the Vine Street Expressway, over strong opposition from residents of Chinatown, but could not overcome neighborhood resistance to a planned Crosstown Expressway along South Street.

In Center City, redevelopment sought to compete with the appeal of suburbia with a new mix of residential, recreational, and commercial space, including high-rise apartment buildings and the suburban-style Gallery shopping mall on Market Street. West of City Hall, the Penn Center complex of office buildings rose in the corridor where an aging viaduct known as the “Chinese Wall” had carried trains into the old Broad Street Station. Around Independence Hall, historical parks managed by the state and federal governments replaced blocks of commercial buildings. South of Independence Hall, by removing and resettling predominantly ethnic and poor residents, then preserving and restoring the best of their colonial-era homes, urban renewal transformed the old Jewish Quarter into upscale Society Hill. In addition to the urban pioneers who bought and rehabilitated the houses of Society Hill, residents added new vitality to other Center City neighborhoods, for example creating a “Gayborhood” in the vicinity of Thirteenth and Locust Street and an arts community in the abandoned factory lofts east of Third Street and north of Market.

The High-Rise Boom

The continuing revitalization of Center City as a mix of residential and commercial historic ambiance and new development built upon these twentieth-century projects. Beginning in 1976, federal tax credits for historic preservation spurred creation of a new supply of luxury apartments through adaptive reuse of old hotels, factories, and office buildings. A boom in skyscraper construction west of Broad Street occurred after 1987, when One Liberty Place broke a longstanding but unofficial practice of respecting the William Penn statue atop City Hall as the highest point in the city. Other skyscrapers followed, with Comcast surpassing all others for height with its fifty-seven-story headquarters built in 2008 and again with its sixty-story Technology and Innovation Center built between 2014 and 2018. East of Market Street, after retailing suffered the failures and consolidations of department stores, the onetime showcase urban shopping mall, the Gallery, itself became the site of redevelopment into a retail-entertainment complex to be called Fashion District Philadelphia.

In an era of industrial decline, Center City anchored a tourism industry that became increasingly important to the region’s economy. Promoters showcased the birthplace of a nation with museums and historic sites like Independence National Historical Park as well as yearly attractions such as the Mummers Parade, an abundance of public art, and a thriving dining and entertainment scene. To compete for conventions as well as recreational travelers, the Pennsylvania Convention Center opened in 1993, taking up the whole of four city blocks between Arch and Race Streets from Eleventh Street to Thirteenth (then more than doubling in square footage with an extension to Broad Street in the 2010s). Redevelopment in service to tourism also occurred in Independence National Historical Park, which gained a block-long visitor center, an expanded exhibit hall for the Liberty Bell, and the National Constitution Center, and nearby a Museum of the American Revolution.

Stewards of Philadelphia’s Center City, like those in other American cities, grappled with the challenge of preserving the past while ensuring a secure future for the city and its residents. Beginning in 1991, the Center City District—a business improvement district—supplemented city services to improve quality of life with initiatives ranging from street cleaning to development of Dilworth Park adjacent to City Hall and Sister Cities Park on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. By the early decades of the twenty-first century, new attention turned toward reintegrating the Delaware River waterfront into the urban grid, and the Schuylkill River Trail opened on the western edge of the original city plan. By 2017, an estimated 190,000 of Philadelphia’s 1.5 million residents lived in Center City and adjacent blocks north to Girard Avenue and south to Tasker Street, including a high concentration of young professionals and increasing numbers of older residents relocating from the suburbs. In a city of many neighborhoods, Center City remained a heart of political and cultural activity and a visible expression of Philadelphia’s growth and change—not only a geographic location, but a signpost of urban vitality.

Catharine Dann Roeber is associate professor of decorative arts and material culture at the University of Delaware and the author of the PhD dissertation Building and Planting: Material Culture, Memory, and the Making of William Penn’s Pennsylvania, completed at the College of William and Mary in 2011. Charlene Mires is professor of history at Rutgers-Camden and editor-in-chief of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Neighborhoods

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University

Gallery

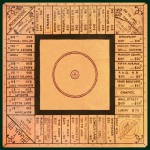

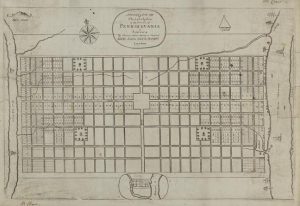

Thomas Holme Map, 1683

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Thomas Holme (1624-95) surveyed what would later be known as Center City at the request of William Penn (1644-1718), creating a river-to-river grid layout with five public squares. Penn hoped development would occur simultaneously along both the Schuylkill (shown on the left side of this map) and Delaware River waterfronts, and along High (Market) Street. The Great Fire of London, which ravaged that city in 1666, inspired Holme to create wider streets, larger land parcels, and plenty of open spaces to prevent a potentially deadly fire from engulfing the city. In practice, development was densely concentrated along the Delaware for most of the city’s early history. This is the first map of the city plan, drawn by Holme and published in London in 1683.

Elfreth's Alley (2013)

Elfreth’s Alley, which has existed for three centuries as a residential enclave, was not included in William Penn’s original plans for Philadelphia. Demand for land in proximity to the Delaware River erased Penn’s dream of a bucolic country town composed of wide streets. As Philadelphia became a bustling city, artisans and merchants purchased or rented the in-demand property close to the ports where goods and materials arrived daily. By 1700, most of the population of Philadelphia settled within four blocks of the Delaware River. This led to overcrowding, and landowners recognized that tradesmen needed alternate routes to the river through the crowded streets Penn had laid out decades earlier. Landowners Arthur Wells and John Gilbert combined their properties between Front and Second Streets to open Elfreth’s Alley, named after silversmith Jeremiah Elfreth, as a cart path in 1706. (Photographed in 2013 for The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia by Jamie Castagnoli)

--Text by Joanne Danifo

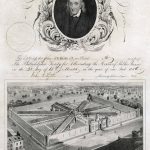

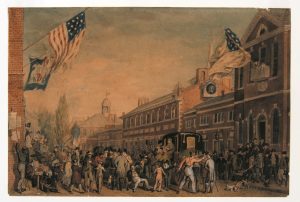

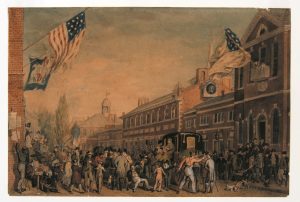

Election Day at the State House, 1815

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

During the Colonial Era, Philadelphia served as the seat of Pennsylvania’s provincial government and home to the Pennsylvania State House, later renamed Independence Hall. After the state government moved to Harrisburg, the hall housed Charles Willson Peale’s natural history museum and almost faced demolition; the wooden steeple and two wings were removed before the state sold the structure to the city in 1816. This scene by John Lewis Krimmel (1786-1821) shows an election day crowd in 1815, with the steeple-less State House in the background and Congress Hall, seat of the United States Congress from 1790 to 1800, in the foreground. Both buildings were incorporated into Independence National Historical Park after its founding 1948. While this park and its mall preserved a number of the city’s early civic buildings, its construction led to the demolition of much of the surrounding neighborhood, including office buildings, factories, and part of “Bankers Row,” and transformed the area from a business district to a tourist destination.

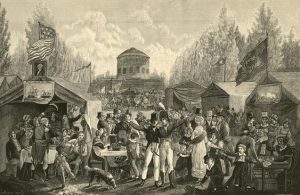

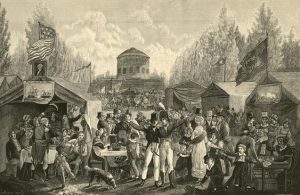

Fourth of July Celebration in Centre Square, Philadelphia

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

William Penn’s original plan for Philadelphia included five public squares: Northeast (Fitler), Southeast (Washington), Southwest (Rittenhouse), and Northwest (Logan) surrounding Center (Penn) square. Penn hoped that Center Square would become the heart of Philadelphia’s civic realm, and in 1870 this goal was finally realized when a referendum selected it as the site of the new City Hall. But prior to that, Center Square acted as home to a pump house designed by Benjamin Latrobe (1764–1820) between 1801 and 1829 that supplied water to the city through a gravity-fed system from the Schuylkill.

The pump house serves as the background for this 1819 sketch by John Lewis Krimmel (1786-1821) depicting a raucous Fourth of July celebration. In keeping with the city’s namesake as the City of Brotherly Love, the crowd in Krimmel’s drawing spans the city’s demographics, with young and old men and women, children, African-Americans, people in Quaker attire and elaborate military costumes all celebrating communally.

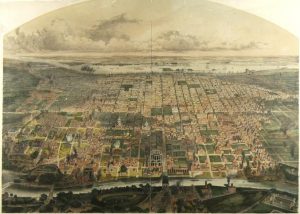

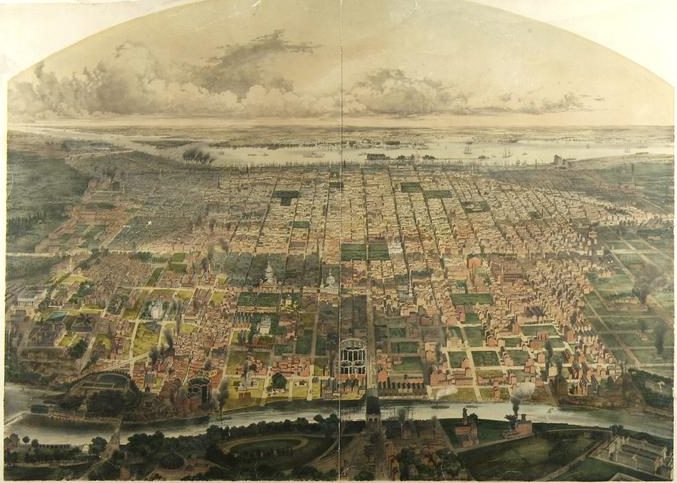

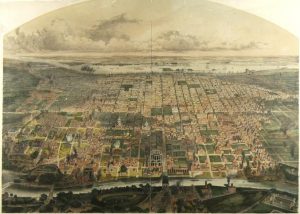

Center City from Schuylkill River, 1857

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

By the mid-nineteenth century, the city had expanded westward from the Delaware River waterfront, although development on the Schuylkill River remained largely industrial. This 1857 map, drawn from the west bank of the Schuylkill, shows the city’s first gas works and factories on the east bank. The denser residential and commercial areas were still concentrated east of Broad Street. By the end of the century, mass transportation systems like streetcars helped shift residential development west and north by allowing people to commute easily from their homes to work.

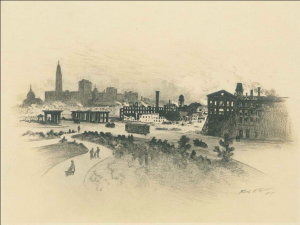

Theaters in the Tenderloin

Although nineteenth and twentieth-century civic leaders promoted the city as an attraction for convention-goers and other visitors, they downplayed the city’s more unseemly sections. The tenderloin or “vice” district and “furnished room” district developed around Ninth and Race Streets. and along Vine Street., east of North Broad. These areas, home to a concentration of brothels, nightclubs, bars, gambling, and drugs, which emerged in the nineteenth century and flourished in the twentieth century, were tolerated, if not openly supported by surrounding residents and City officials until late twentieth-century century clean-up campaigns and shifts in demographics diminished their reputation as dens of iniquity. This 1938 photograph shows the Auditorium Theater (left) and New Garden Theater, two of the many entertainment venues that lined N. Eighth Street in the first half of the twentieth century. Many of these theaters promoted burlesque, minstrel shows, and other less-than-reputable entertainment.

Broad Street Station

The Pennsylvania Railroad’s Broad Street Station provided passenger service from the suburbs to Center City and the growing Broad Street cultural corridor beginning in 1881. Trains came into the heart of the city on elevated viaducts, most notably the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks that ran from the Schuylkill River to the Broad Street Station along Filbert Street, bridging the numbered streets along the way. Later known as the “Chinese Wall,” the viaduct rendered the area north toward Logan Square far less desirable than the area to the south, which was already anchored by fashionable Rittenhouse Square.

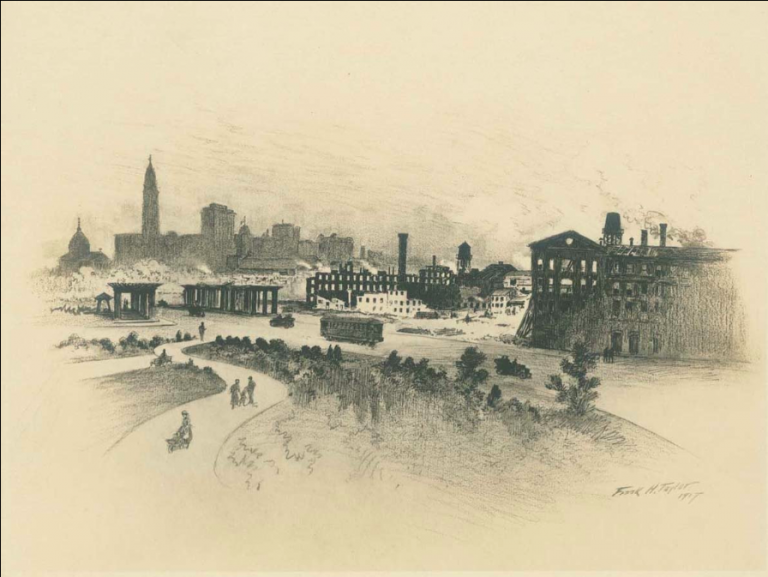

Swept Away from the Parkway Vista

Library Company of Philadelphia

The Benjamin Franklin Parkway, completed in 1918, provided Center City with a new cultural corridor in its northwest quadrant and allowed easy passage to Fairmount Park. Construction required the demolition of over 1,300 buildings. Among these was the Medico-Chirurgical College, shown to the left of this 1917 drawing by Frank H. Taylor (1846-1927), which was dismantled piecemeal leaving just a columned entryway standing until that, too, fell to the wrecking ball. The Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul, completed in 1864, was one of the few buildings along the Parkway corridor that was spared.

Edmund Bacon